The NTSB preliminary report on the double-fatality crash of a vintage Lockheed 12A was published this week. From the report:

According to the operator’s representative, he thought the co-pilot lowered the flaps as part of the functional test during the preflight inspection. During the engine start, the ground crew warned the flight crew with hand and arm signals that the flaps were extended. From the ground crews experience and observations with the accident airplane, they felt that the flaps were fully extended during taxi and the takeoff on runway 26R.

Photo and caption from the NTSB preliminary report

Witnesses located at the airport reported that they observed the accident airplane taxi to the runway and takeoff with the flaps extended. Video of the accident flight also captured the flaps extended during the initial climb. According to witnesses and video, as the airplane reached the departure end of the runway, about 200 – 300 ft above ground level, the airplane pitched up, turned to the left, and entered a nose low attitude as it descended into terrain, where a post-crash fire ensued.

Flaps were originally added to airplanes as drag devices. They allow an airplane to descend steeply as they usually did it at the time, in a slip, while remaining in coordinated flight and longitudinally aligned with the runway—increasingly important in the 12A’s day as airplanes grew in size and filled with paying passengers who might not appreciate the artistry of rounding out of a forward slip.

It was only later that flaps were modified to increase lift as well as create drag. With this innovation it became advantageous in some airplanes under some circumstances to take off with flaps extended. When doing so it’s almost also proper to take off with partial flaps…and almost never with full flaps.

Why is that? There are likely several reasons, but one is the desire to maximize the ratio of additional lift from the flaps to the drag they create, compared to a flaps-up takeoff. How does that ratio compare? The answer will vary by airplane type, perhaps substantially. For one data set look at what I learned in my employer’s 1981 A36 Bonanza.

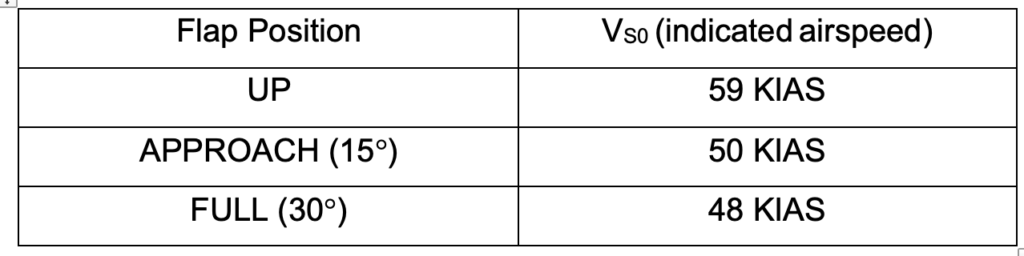

I was calibrating the angle of attack indicator in the Bonanza. Part of the procedure is to precisely determine the power off stall speed at all flap positions. From there you multiply each figure by 1.3, then fly in that configuration at that speed within a knot or two for a period of time while you push the proper buttons to calibrate the device. I flew three test stalls each way on a smooth day and found consistent results within a knot or two for each configuration. The results revealed something pretty interesting.

Stall speeds at the tested weight (I flew them back-to-back as quickly as possible so the airplane weight was essentially unchanged) were as follows:

Extending 15 degrees of flaps reduced stall speed by nine knots—a 15% reduction. Obviously the first half of flap extension in this airplane adds a lot of lift (so it stalls at a much lower speed) and not much drag.

The second half of full flap extension, however, only reduced stall speed by another two knots compared to the half-flaps condition—only 4%! Clearly the second half of flap extension in this airplane is almost exclusively drag, with little additional lift.

What’s the practical application of this knowledge? Well, several things actually. The additional lift of partial flapsallows you to fly at a slower speed with relatively little additional drag. Under some conditions using partial flaps improves takeoff and initial climb performance. Half flaps do not create enough descent to be confused with extended landing gear if you deploy half flaps before putting the wheels down in a retractable gear airplane—a common, if incorrect, argument against using partial flaps in flight.

With half flaps extended the airplane is more stable at a slower speed, in part because extending partial flaps moves the wing’s center of lift aft, which has the same effect as moving the center of gravity forward—a stability enhancer.

Full flaps, on the other hand, does almost nothing to increase lift. As previously noted, the second half of flap extension in this model is drag. Further, full flap extension in many types of airplane tends to lower the pitch attitude for a given speed. If the pilot flies the pitch attitude he/she would without the flaps extended the airplane will fly slower and at a higher angle of attack. That, and the drag, can lead to a stall.

That’s why in a go-around or in a stall, you want to lower angle of attack with aggressive elevator input, then retract the flaps away from the full down condition, then incrementally retract flaps as you manage AoA and transition to a safe and normal climb speed.

That’s also why you want to be doubly certain the flaps are not fully down before entering the runway for takeoff. Confirming flaps are in the correct position is among the so-called “Killer Items” to check before takeoff, as described in this article by author/legend (and FLYING LESSONS reader) J. Mac McClellan.

Design a Flight Review around comparing the change in stall speed between different amounts of flap extension in the airplane you fly, to see if your rules of thumb are similar to what I found in an A36 or if the aerodynamics of your type are such that you can derive rules of thumb different from what I found in the Bonanza.

Then practice stalls in the takeoff flap configuration and also from full flaps—at a safe altitude, of course—to confirm or refute the wisdom of retracting flaps early in the go-around sequence in the airplane you fly. The rules are probably not the same for all airplane types.

You don’t have to wait two years for your current Flight Review to expire before you do a minimum of one hour each of ground and flight instruction to learn something new like the flap configuration characteristics and performance of your aircraft. And, if you earn a Flight Review endorsement early it resets the 24-month calendar. So you’ll become a safer pilot sooner.

Questions? Comments? Supportable opinions? Let us know at [email protected].

Debrief:

Readers write about recent FLYING LESSONS:

I’m cutting this short this week as I pack for Oshkosh. I’ll get to some reader mail and insights next week.

More to say? Let us learn from you, at [email protected]

Share safer skies. Forward FLYING LESSONS to a friend.

Please help cover the ongoing costs of providing FLYING LESSONS through this secure PayPal donations link.. Or send a check made out to Mastery Flight Training, Inc. at 247 Tiffany Street, Rose Hill, Kansas USA 67133. Thank you, generous supporters.

Thank you to our regular monthly financial contributors:

Steven Bernstein, Montclair, NJ. Robert Carhart, Jr., Odentown, MD. Randy Carmichael, Kissimmee, FL. Greg Cohen, Gaithersburg, MD. John Collins, Martinsburg, WV. Paul Damiano, Port Orange, FL. Dan Drew. Rob Finfrock, Rio Rancho, NM. Norman Gallagher. Bill Griffith, Indianapolis, IN. Steven Hefner, Corinth, MS; Ellen Herr, Ft Myers, FL. Erik Hoel, Redlands, CA. Ron Horton. Robert Hoffman, Sanders, KY. David Karalunas, Anchorage, AK. Steve Kelly, Appleton, WI. Karl Kleiderer. Greg Long, Johnston, IA. Rick Lugash, Los Angeles, CA. Richard McCraw, Hinesburg, VT. David Ovad, Resiertown, MD. Steven Oxholm, Portsmouth, NH. Brian Schiff, Keller, TX. Paul Sergeant, Allen, TX. Ed Stack, Prospect Heights, IL; Paul Uhlig, Wichita, KS. Richard Whitney, Warrenton, VA. Jim Preston, Alexandria, VA. Johannes Ascherl, Munich, Germany. Bruce Dickerson, Asheville, NC. Edmund Braly, Norman, OK. Steven Hefner. Lorne Sheren, New Vernon, NJ

And thanks to these donors in 2024:

Jim Lara, Joseph Stadelmann, Dixon Smith, Barry Warner, Wayne Mudge, Joseph Vandenbosch, Ian Campbell, Jay Apt, John Kimmons, Derek Rowan, Michael Maya Charles, Ron Horton, Lauren McGavran, Gerald Magnoni, Amy Haig, Rod Partlo, Brent Chidsey, Mard Sasaki-Scanlon, SABRIS Aviation (Dave Dewhirst), Edmund Braly, Joseph Orlando, Charles Lloyd, Michael Morrow, Abigail Dang, Thomas Jaszewski Danny Kao, Gary Garavaglia, Brian Larky, Glenn Yeldezian, David Yost, Charles Waldrop, Robert Lough. Gilbert Buettner. Panatech (Henry Fiorientini). Dale Bleakney. Mark Kolesar. John Winter. Donald Bowles

Pursue Mastery of Flight

Thomas P. Turner, M.S. Aviation Safety

Flight Instructor Hall of Fame Inductee

2021 Jack Eggspuehler Service Award winner

2010 National FAA Safety Team Representative of the Year

2008 FAA Central Region CFI of the Year

FLYING LESSONS is ©2024 Mastery Flight Training, Inc. For more information see www.thomaspturner.com. For reprint permission or other questions contact [email protected].