FLYING LESSONS uses recent mishap reports to consider what might have contributed to accidents, so you can make better decisions if you face similar circumstances. In most cases design characteristics of a specific airplane have little direct bearing on the possible causes of aircraft accidents—but knowing how your airplane’s systems respond can make the difference in your success as the scenario unfolds. So apply these FLYING LESSONS to the specific airplane you fly. Verify all technical information before applying it to your aircraft or operation, with manufacturers’ data and recommendations taking precedence. You are pilot in command and are ultimately responsible for the decisions you make.

FLYING LESSONS is an independent product of MASTERY FLIGHT TRAINING, INC. ©2024 Mastery Flight Training, Inc. All rights reserved.

Pursue Mastery of Flight™

This week’s LESSONS:

AVWeb reported a fuel leak this week. Normally such a discovery would not warrant widespread media (or any media at all). This fuel leak, however, was on the underside of a Beech C55 Baron leased by the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA) and being used as a flying demonstrator of General Aviation Modifications, Inc.’s (GAMI’s) G100UL unleaded 100 octane aviation gasoline. The Baron demonstration involves comparison testing of this (relatively) new Supplemental Type Certificate (STC)-approved fuel in the left engine fed by left-wing fuel tanks, with standard 100LL avgas in the right engine and that engine’s right-wing tanks. I’ve had the opportunity to fly in the AOPA Baron test and found G100UL to work as advertised, at least during my very short experience with AOPA’s fuel-demo pilot.

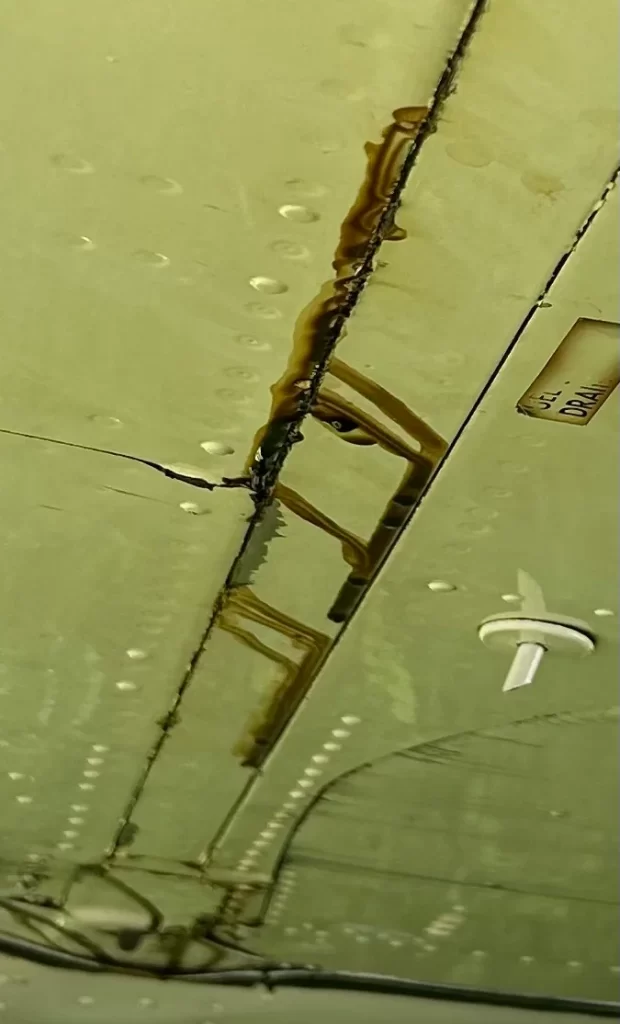

AVWeb’s photo of the AOPA-leased Baron’s fuel leak

The fuel stain found while the airplane was on display at Oshkosh is on the underside of the left-wing tanks. The implication—mere speculation at this point—is that the leak might be the result of contact with something in the unleaded fuel. Fuel bladder leaks in Barons are common as components age, however, as are leaks in fuel seals and gaskets around line connections, fuel level transmitters and other parts. Maintenance experts suggest replacing the rubber fuel bladders at 20 years in service and some sources say the AOPA-leased C55 fuel bladders have twice that time in service. Absolutely, the cause of the leak must be determined and G100UL fuel eliminated (or, however unlikely, confirmed) as its cause.

But that’s not the LESSON I draw from AVWeb’s report this week.

Say you flew your airplane to Oshkosh, or somewhere else. While on the ground there you spot (or someone points out) a fuel stain on the underside of your aircraft. Or maybe it’s a wrinkle in the wing skin, or a minor crack along a fuselage rivet line, or a cracked windshield. Whatever the particulars, you become aware of a discrepancy…far from home.

Do you leave the festivities to contact a mechanic, and arrange to have your aircraft evaluated? Or do you rationalize the discrepancy, perhaps come up with some sort of mitigation you think will reduce the risk as you fly the airplane home to have your regular mechanic check it there?

If you do get a mechanic to check it out, and he or she tells you “You definitely need to get that fixed, but it should be okay to get you home,” do you accept the advice?

Bear in mind that from memory I’ve reported on at least two Bonanza wing explosions, one Baron wing explosion and one explosion of a wing on a Beech Queen Air over the years in my Beech Weekly Accident Update—all, thankfully, occurring on the ground—that were eventually attributed to leaks in wing fuel tanks or lines ignited by electrical wiring passing along the wing leading edge where fuel components are mounted. In most of these events the explosion occurred immediately when the pilot turned on the strobe lights prior to takeoff. I seem to recall similar events reported in twin Cessnas, and I expect it’s happened in other airplane types also. But I don’t currently follow non-Beech accidents and incidents as closely.

It’s easy sitting in my home office writing this report to say, “No, I’ll ground the airplane until the discrepancy is repaired.” It’s easy to say the same reading this blog at zero airspeed and one G, with no pressure—real or self-imposed—to fly home.

But how easy would it be to make that same call hundreds of miles from your home as all your friends fly away and you really need to get to home and work?

That’s my FLYING LESSON this week: As you consider this scenario without the stress of the actual moment, how will you maintain the discipline to resist temptation (and even a mechanic’s suggestion) to brush off what could be a major hazard? What can you decide now to make it easier to make a good decision then?

Questions? Comments? Supportable opinions? Let us know at [email protected].

Debrief:

Readers write about recent FLYING LESSONS

Reader Jim Piper writes about my most recent LESSONS:

Tom, I respectfully disagree with one of your conclusions regarding the use of approach flaps. With the Bonanza while approach flaps provides more lift hence lowered stall speeds, there is enough drag present to confuse pilots with relatively low Bonanza flight experience or those who fly infrequently as to the landing gear’s position particularly if some form of distraction is introduced or present and therefore should be treated with extreme caution if deployed before extending the gear. A classic example would be a full traffic pattern when the towers sends you on an extended downwind behind several other aircraft. The obvious solution is to extend approach flaps and reduce speed further to decrease one’s distance from the airport and maintain separation interval. However, if the pilot becomes distracted because his spacing isn’t working out as anticipated and the airplane is descending with a little power on he may forget the gear, particularly if he’s preoccupied with whether the preceding aircraft is going to clear the runway.

The other one I fail to understand is the pilot who habitually insists on approach flaps for takeoff regardless of aircraft weight, runway length, or field elevation.

Regarding use of Approach flaps for their designed purpose, I’ll have to try to video the airplane’s response to partial flaps and normal power reduction from downwind in the pattern some day. Regardless, it’s the difference between procedure and technique. The correct procedure is “extend the landing gear before touching down on the runway.” There are any number techniques to assure that procedure is completed, which I’ve addressed here and elsewhere for 34 years. I accept that different people do things different ways. The ultimate solution: regardless of whatever else you do, confirm gear extension before crossing the runway threshold every time, and go around immediately if the gear is not confirmed to be down, without hesitation.

To your second point, that is very type- and even model-specific, as well as variable for a specific aircraft based on its weight and the current environmental conditions. Notice that Beech calls the preselectable partial flap position approach flaps, and not takeoff flaps. Thank you, Jim.

Read Jan Jansen also writes about the July 18 report:

“Witnesses located at the airport reported that they observed the accident airplane taxi to the runway and takeoff with the flaps extended.”

FYI, you don’t “takeoff.” You “take off” (TWO words!). There’s a distinct grammatical difference between “takeoff” and “take off.” You should learn it.

True, to “take off” is a verb while “takeoff” is a noun. Perhaps the NTSB, which I was quoting directly in the excerpt you cite, needs to learn that (note I put longer quotes in blue font to distinguish others’ words). Not that I don’t sometimes make mistakes in these after-hours musings, so thanks for keeping me precise, Jan.

South African reader Bernard Monteverdi adds to the July 18 LESSON:

I have experienced an inadvertent full flaps departure.

I own and a fly a 1975 BE55 [Beech Baron twin] out of Cape Town International Airport (FACT). Part of my preflight checks is the extension of the flaps in their two configurations to ensure that they do indeed extend and do so symmetrically.

Having had a few dead batteries over time, I have come to leave these extended and retract them at the after-start checks. As you can imagine not being part of the after-start checks, I have been known to forget them. Usually I pick this oversight up at the pre-take off checks but …. One day I didn’t.

Nothing noticeable during the takeoff roll but on rotation, the airplane climbed sluggishly. Making sure all hand controls were fully forward (pitch, throttle, and mixture) I realised the flaps were fully extended. As I gained a decent positive rate of climb, I slowly retracted the flaps and gear and flew normally.

I think what saved me was the power of two IO-520 Continentals at full thrust (285hp), being alone in the airplane and therefore well below maximum takeoff weight (MTOW) by more than 1000 pounds, and 3500 metres (11,500 feet) of runway.

Weak battery or no weak battery, I now retract the flaps during the pre-flight and check that again after start and pre-flight.

Regards and thanks for always interesting articles.

Given that flap extension is not critical to takeoff in your particular aircraft type—in fact, it’s discouraged—might you eliminate the preflight test altogether and avoid the risk of forgetting again? You could make a periodic test after landing, or even in the hangar. I favor doing these sorts of checks when I’m not planning to fly and pressured to rationalize a discrepancy to get in the air. If you find a problem while in the hangar you have time to address it before your next flight, or make other travel plans if you cannot. I do appreciate your diligence in adjusting technique to mitigate a hazard. Thank you, Bernard.

More to say? Let us learn from you, at [email protected]

Share safer skies. Forward FLYING LESSONS to a friend.

Please help cover the ongoing costs of providing FLYING LESSONS through this secure PayPal donations link. Or send a check made out to Mastery Flight Training, Inc. at 247 Tiffany Street, Rose Hill, Kansas USA 67133. Thank you, generous supporters.

Thank you to our regular monthly financial contributors:

Steven Bernstein, Montclair, NJ. Robert Carhart, Jr., Odentown, MD. Randy Carmichael, Kissimmee, FL. Greg Cohen, Gaithersburg, MD. John Collins, Martinsburg, WV. Paul Damiano, Port Orange, FL. Dan Drew. Rob Finfrock, Rio Rancho, NM. Norman Gallagher. Bill Griffith, Indianapolis, IN. Steven Hefner, Corinth, MS; Ellen Herr, Ft Myers, FL. Erik Hoel, Redlands, CA. Ron Horton. Robert Hoffman, Sanders, KY. David Karalunas, Anchorage, AK. Steve Kelly, Appleton, WI. Karl Kleiderer. Greg Long, Johnston, IA. Rick Lugash, Los Angeles, CA. Richard McCraw, Hinesburg, VT. David Ovad, Resiertown, MD. Steven Oxholm, Portsmouth, NH. Brian Schiff, Keller, TX. Paul Sergeant, Allen, TX. Ed Stack, Prospect Heights, IL; Paul Uhlig, Wichita, KS. Richard Whitney, Warrenton, VA. Jim Preston, Alexandria, VA. Johannes Ascherl, Munich, Germany. Bruce Dickerson, Asheville, NC. Edmund Braly, Norman, OK. Steven Hefner. Lorne Sheren, New Vernon, NJ

And thanks to these donors in 2024:

Jim Lara, Joseph Stadelmann, Dixon Smith, Barry Warner, Wayne Mudge, Joseph Vandenbosch, Ian Campbell, Jay Apt, John Kimmons, Derek Rowan, Michael Maya Charles, Ron Horton, Lauren McGavran, Gerald Magnoni, Amy Haig, Rod Partlo, Brent Chidsey, Mard Sasaki-Scanlon, SABRIS Aviation (Dave Dewhirst), Edmund Braly, Joseph Orlando, Charles Lloyd, Michael Morrow, Abigail Dang, Thomas Jaszewski Danny Kao, Gary Garavaglia, Brian Larky, Glenn Yeldezian, David Yost, Charles Waldrop, Robert Lough. Gilbert Buettner. Panatech (Henry Fiorientini). Dale Bleakney. Mark Kolesar. John Winter. Donald Bowles

NEW THIS WEEK: David Peterson

Pursue Mastery of Flight

Thomas P. Turner, M.S. Aviation Safety

Flight Instructor Hall of Fame Inductee

2021 Jack Eggspuehler Service Award winner

2010 National FAA Safety Team Representative of the Year

2008 FAA Central Region CFI of the Year

FLYING LESSONS is ©2024 Mastery Flight Training, Inc. For more information see www.thomaspturner.com. For reprint permission or other questions contact [email protected].