FLYING LESSONS for December 21, 2023

FLYING LESSONS uses recent mishap reports to consider what might have contributed to accidents, so you can make better decisions if you face similar circumstances. In most cases design characteristics of a specific airplane have little direct bearing on the possible causes of aircraft accidents—but knowing how your airplane’s systems respond can make the difference in your success as the scenario unfolds. So apply these FLYING LESSONS to the specific airplane you fly. Verify all technical information before applying it to your aircraft or operation, with manufacturers’ data and recommendations taking precedence. You are pilot in command and are ultimately responsible for the decisions you make.

FLYING LESSONS is an independent product of MASTERY FLIGHT TRAINING, INC.

Pursue Mastery of Flight

Download this report as a pdf.

This week’s LESSONS:

Enjoy the Fourth

Before you think I have my holidays several months out of phase (or if you’re one of my many international readers and do not immediately get the reference), this week’s LESSON is a short reminder that more than anything else personal and business aviation gives us flexibility. Some of this flexibility comes from choosing not only the departure point and the destination, the route and the altitude for a flight, but also making it happen at a time of your own choosing.

You probably think of flying as a three-dimensional activity. But my experience—as an instructor, as a student of mishap history, and in an honest review of my own habits—suggests that many of us don’t really think in three dimensions. We tend to fly “direct,” or as close to direct as possible…often flying directly into areas of storms or other hazards. We tend to have favorite cruising altitudes we use for some reason or another even when better alternatives exist—I’m reminded of a fatal icing accident in a turbocharged piston twin where the cloud bases were at 17,000 feet but the pilot chose to fly in the Flight Levels and spun in from that height after encountering heavy ice. I challenge pilots to plan and think in three dimensions, to select the best route and the best altitude for conditions as they exist at the time. You might have a default altitude and routing for a flight, but be willing to modify it as needed.

There’s yet another dimension within which to plan and maneuver—the dimension of time. Most cliches` have an element of truth. One is that it’s usually clear and sunny when the NTSB arrives to begin its investigation (my Air Safety Investigator friends probably dispute this). Regardless, when planning a flight look beyond even three-dimensional flying to include the fourth dimension—is now the time to go, can I wait until my planned departure time, or should I delay? Often just a small change in one or more of the dimensions can turn an uncomfortable flight into a smooth one, inflight hazards into risks well managed, and a cancelled trip into one that works…maybe not on schedule, but as my friend and FLYING LESSONS reader Martin Pauly lamented on FaceBook this week, sometimes it’s a victory to arrive within 48 hours of your plan.

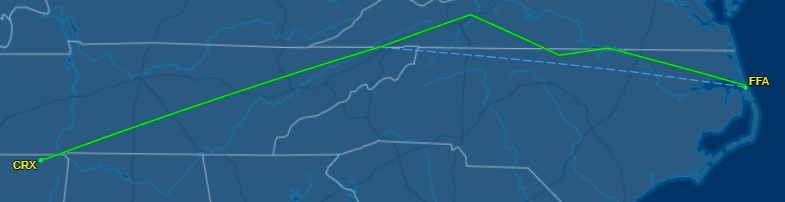

One good example of four-dimensional flying is my boss CK Lee’s return from the First Flight Society induction of Walter and Olive Ann Beech at Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina on the 120th anniversary of the Wright Brothers’ first controlled, powered flights. Flying my employer’s aircraft, he chose to leave a little early to avoid a major storm coming up from the southwest, angling around the north side of the low pressure system at the lowest safe IFR altitude permitted by terrain (and, low and westbound north around a low in the Northern Hemisphere, picking up a good tailwind in the process).

A successful four-dimensional flight (and I don’t say so just because it was my boss flying), minus the radar images that reflected conditions at the actual time of passage.

It seems like a minor victory, flying well out of the way a little off schedule at an altitude he might not have otherwise chosen. But it worked. As we’ve discussed here before, it’s not an example many will see because it did not lead to a mishap and therefore will not be publicly investigated and documented. Yet although the record does not shine, it is a shining example of what thousands of pilots do every day—and the type of four-dimensional flying we must all do every time to get safety, utility and enjoyment as pilot-in-command.

So, enjoy the fourth—the four-dimensional opportunities available if you’re making a holiday trip this week, and on every flight you make all year ‘round. It’s a simple LESSON, but that makes it easy to learn.

Merry Christmas to all who observe the holiday; happy and safe New Year and the coming year in the skies for us all!

Questions? Comments? Supportable opinions? Let us know at [email protected].

Debrief:

Readers write about recent FLYING LESSONS

Some heavy-hitter readers wrote about last week’s LESSONS rethinking landing gear position in an off-airport landing in retractable gear airplanes. Well-known airline pilot and aviation educator Brian Schiff writes:

I am in complete agreement with your line of thinking with regard to crash-landing with the gear up or down. This has caused me to rethink what I teach and will probably include a lesson on teaching/discovering the actual performance effects of dropping the gear at the last minute. The Lake Placid accident is compelling.

Robert Thorson adds:

Emergency landings like everything in aviation are a combination of complexity and skill. ONE OF THE BEST PILOTS I HAVE EVER FLOWN WITH, pulled the throttles of a 747 to idle and “dead sticked’ us onto the runway at Colorado Springs configuring at the last second along the approach path. Obviously, I was in a state of fear along with the flight engineer. But this aviator had perceptive skills and flying skills far ahead of any human I have ever known. It was flawless.

Now to the rest of us mortal aviators… It is my belief that once you have a successful pattern set for landing do not change it. Not in track or configuration. Energy management is the name of the game so any gear or flap change will result in changing the energy balance built for a successful landing. The other possibility is the gear down scenario causes a tear in the fuel tanks resulting in a fire.

The other trick is to carry the best glide speed as far as possible. If you slow down trying to reduce impact, you may stall high or drop a wing cartwheeling the aircraft as one wing touches the ground. If you have the speed between best glide and stall you can maneuver horizontally and vertically (energy) at the last second to avoid unseen obstacles while maintaining control.

Obviously, each pilot must make his own decisions but considering skill, knowledge and proficiency who can make all the correct actions under pressure? Keep it simple and don’t change any variables. A 9G landing requires only 150 feet of run.

Now more from Julian Yates:

Thanks for the discussion of wheels up or down forced landings in retractables.

When I learned to fly out of Jandakot Airport near Perth, Western Australia (some years ago), my CPL training was in retractable M201s. Much of the training was done out over the (seemingly endless) wheat and grazing plains east of Perth. The fields there were mostly flat, cleared and had hard surfaces except after very heavy rain, a rare event. I was taught to plan to land gear down in those situations, and indeed, some of the practices were to full stop landings (the instructors knew the owners, had permission and called first). It gave you a good appreciation of the drag effect of lowering the gear and adjusting the approach.

For many years after that, most of my flying was in fixed gear aircraft, so the option to land gear up wasn’t available.

Moving to the east coast of Australia (Canberra), I became a part-owner of a Bonanza (the venerable VH-FIM, which you may have seen). Here, the general geography was quite different for forced landings – still plenty of paddocks (but smaller), however the ground was often soft and there was no real way to be certain of surface condition. So, I changed my thinking and pre-take off check: after gear up, unless there was a ginormous runway ahead, all engine failure landings were to be gear up. Enroute was the same.

FIM’s survived at least two gear up landings, and I had access to one of the repair reports and apart from flap, prop and engine damage, the airframe suffered no significant damage and the occupants all walked away. Both they and FIM flew again.

Now this is my experience; others will have different views, but for me, in a retractable aircraft, an engine failure situation, gear up is the choice unless there is a really good reason to lower it.

Retired SIMCOM instructor Dan Bindle comments:

Today’s update triggered several thoughts!

Three decades ago at the 12,000 hour stage in my flying experiences, I had an occasion of the elevator linkage disconnect while ‘in flight’ while flying an ultralight. The horizontal stabilizer allowed comfortable pitching up or down with power increases or decreases. I elected to land in a nearby hay field where the hay had just been harvested before some additional ‘challenge’ entered into the flight equation!! No problems with a pattern and final approach until that point just short of the landing!

I was probably about a wingspan above the ground when my ‘learned habit’ behavior made the ‘power reduction’. The resulting hospitalization provided me the opportunity to think about the fact that a lot of our behaviors are ‘learned habits’, often referred to as ‘habits’. For future landing events, be careful making any abrupt ‘power reductions’ while getting close to the ground with a ‘minimal mass in motion’ (therefore power dependent) type airplane.

Another interesting experience occurred just past the 20,000 hour stage in my flying experiences. I was alone in a half century old Mooney. I had accomplished a practice ILS approach with a clearance for a touch and go on this looooong runway. There had been some ‘kissing’ of the pavement before continuing the planned ‘go around’. As I began the climb, with gear and flaps still down, I was shocked and surprised by the lack of performance, compared to the performance that had become my expectation, following thousands of hours flying several Bonanzas, from the ‘C’ models up through the A 36 of that time, and doing similar ‘go arounds’.

My research, about ground effect, helped me understand how much lower in ground effect the wing of the Mooney was when that tire ‘kissed’ the pavement, compared to how high the wing of the Bonanza was when that Bonanza wheel, at the end of its extended olio was, when that Bonanza wheel ‘kissed’ the pavement.

My research hinted that we get reduced drag when the wing descends to a wingspan above the ground. By the half wingspan altitude we have a 23% drag reduction and at a 10% wingspan, we experience 47% drag reduction. That Mooney wing gets down to about 5%. No wonder there is such a profound difference between ‘kissing’ the surface drag, and beginning the climb drag with that Mooney.

While the ‘gear extension drag’ element in forced landing experiences is important, depth in ground effect, with low wing airplanes may deserve a short paragraph when electing the ‘gear up’ choice. Mooney salesman had to deal with that reduced induced drag, float, at that Mooney, lower depth in ‘ground effect’, when interacting with ‘high wing’ Cessna type people.

Advanced maneuvers instructional specialist Ed Wischmeyer continues:

Another informative, well-written lesson. Here’s a Cessna 177RG-ism that might add to the conversation [relating to the Lake Placid crash referenced in last week’s report]…

For the high wing, retractable gear Cessnas, it was always taught that gear in transit created more drag than gear down. When in doubt, leave the gear down rather than retract it if optimum performance was required. I’m not sure that gear extension drag was commonly taught.

What’s different on the 177RG from all the other RGs are the nose landing gear doors. While other RGs have left and right nose landing gear doors, the 177RG also has a rectangular front gear door. With gear extended, this nose gear door is perpendicular to the airstream. A CFII friend with a 177RG relates that when the gear is extended, this front gear door is an enormous source of drag.

I consider myself relatively knowledgeable about things aeronautical, including high wing Cessnas. But if I didn’t know about 177RG gear down drag, it seems reasonable that this factoid may not have been conveyed to C177RG owner Russ Francis when he checked out in the C177RG, and may not have been in McSpadden’s experience. Or it may be a case of negative transfer, that gear down drag in a 177RG was erroneously thought to be comparable to gear down drag in other airplanes. Perhaps a reader with more Cessna experience than I can give a more complete explanation.

Looking at gear/up down another way, consider transfer from training to real world scenarios. If a pilot always puts the gear down in engine out training, that might become unthinkingly habitual.

Lots to think about.

Airshow pilot and instructor Doug Rozendaal adds:

As for gear up or down, here what I say: Unless you are willing to bet your life on the surface, the default is gear up. There are exceptions to every rule, one being dense canopy trees, I’d go gear down for that.

Reader Ed Loskill notes:

Tom, this is one of the best arguments for changing an aviation belief I’ve ever read… with near bullet-proof justification. Good, powerful and humble writing . . . Thank You.

And well-known flight instructor and retired TWA director of training Wally Moran concludes:

Tom, like you I have changed my position on gear up vs gear down. During my airline career, we were taught that an off field landing should be gear down thinking that tearing off the gear would help to dissipate the energy. Perhaps that’s true given the greater mass, but like you, I see accident reports where the landing gear on GA airplanes only contributed to a quick stop. Sometimes with the plane upside down. Then there is the additional history of coming up short. And recently the McSpadden accident which came so close to being successful.

I too am convinced, the odds are usually better with the gear up.

I guess I wasn’t as alone in my thinking as I supposed. Thank you, everyone. More to say? Let us learn from you, at [email protected].

Please help cover the ongoing costs of providing FLYING LESSONS through this secure PayPal donations link. Or send a check made out to Mastery Flight Training, Inc. at 247 Tiffany Street, Rose Hill, Kansas USA 67133.

Thank you, generous supporters.

Special thanks to these donors for helping with the Mastery Flight Training website rebuild and beyond:

Karl Kleiderer, Jeffery Scherer, Ken Newbury, William Eilberg, Wallace Moran, Lawrence Peck, Lauren McGavran, Stanley Stewart, Stu and Barbara Spindel, Danny Kao, Mark Sanz, Wayne Mudge, David Peterson, Craig Simmons, John and Betty Foose, Kendell Kelly, Sidney Smith, Ben Sclair, Timothy Schryer, Bruce Dickerson, Lew Gage, Martin Pauly, Theodore Bastian, Howard Greenberg, William Webber, Marc Dullude, Ian O’Connell, Michael Morrow, David Meece, Mike Gonce, Gianmarco Armellin, Mark Davis, Jason Ennis, William Moore, Gilbert Buettner, Don Denny, John Kolmos, LeRoy Cook, Mark Finklestein, Rick Lugash, Tom Carr, John Zimmerman, Lee Perrin, Bill Farrell, Kenneth Hoeg, William Jordan Jr., Mark Rudo, Boyd Spitler, Michael Brown, Gary Biba, Meaghan Cohen, Robert Chatterton, Lee Gerstein, Peter Tracy, Dan Drew, David Larson, Joseph McLaughlin, Nick Camacho, Paul Uhlig, Paul Schafer, Gary Mondry, Bruce Douglass, Joseph Orlando, Ron Horton, George Stromeyer, Sidney Smith, William Roper, Louis Olberding, George Mulligan, David Laste, Ron Horton, John Kinyon, Doug Olson, Bill Compton, Ray Chatelain, Rick McCraw, David Yost , Johannes Ascherl, Rod Partio, Bluegrass Rental Properties, David Clark, Glenn Yeldezian, Paul Sherrerd, Richard Benson, Douglass Lefeve, Joseph Montineri, Robert Holtaway, John Whitehead; Martin Sacks, Kevin O’Halloran, Judith Young, Art Utay

NEW THIS WEEK: Mark Still, Charles Lloyd, Danny Kao, Leroy Atkins

Thanks to our regular monthly financial contributors:

Steven Bernstein, Montclair, NJ. Robert Carhart, Jr., Odentown, MD. Randy Carmichael, Kissimmee, FL. James Cear, South Jamesport, NY. Greg Cohen, Gaithersburg, MD. John Collins, Martinsburg, WV. Paul Damiano, Port Orange, FL. Dan Drew. Rob Finfrock, Rio Rancho, NM. Norman Gallagher. Bill Griffith, Indianapolis, IN. Steven Hefner, Corinth, MS; Ellen Herr, Ft Myers, FL. Erik Hoel, Redlands, CA. Ron Horton. Robert Hoffman, Sanders, KY. David Karalunas, Anchorage, AK. Steve Kelly, Appleton, WI. Karl Kleiderer. Greg Long, Johnston, IA. Rick Lugash, Los Angeles, CA. Richard McCraw, Hinesburg, VT. David Ovad, Resiertown, MD. Steven Oxholm, Portsmouth, NH. Brian Schiff, Keller, TX. Paul Sergeant, Allen, TX. Ed Stack, Prospect Heights, IL; Robert Thorson, Reeders, PA. Paul Uhlig, Wichita, KS. Richard Whitney, Warrenton, VA. James Preston, Alexandria, VA.

Pursue Mastery of Flight

Thomas P. Turner, M.S. Aviation Safety

Flight Instructor Hall of Fame Inductee

2021 Jack Eggspuehler Service Award winner

2010 National FAA Safety Team Representative of the Year

2008 FAA Central Region CFI of the Year

FLYING LESSONS is ©2023 Mastery Flight Training, Inc.

For more information see www.thomaspturner.com. For reprint permission or other questions contact [email protected].