Topics this week include: > LESSONS from Down Under > Know thy aircraft > “I failed IMSAFE”

FLYING LESSONS uses recent mishap reports to consider what might have contributed to accidents, so you can make better decisions if you face similar circumstances. In most cases design characteristics of a specific airplane have little direct bearing on the possible causes of aircraft accidents—but knowing how your airplane’s systems respond can make the difference in your success as the scenario unfolds. So apply these FLYING LESSONS to the specific airplane you fly. Verify all technical information before applying it to your aircraft or operation, with manufacturers’ data and recommendations taking precedence. You are pilot in command and are ultimately responsible for the decisions you make.

FLYING LESSONS is an independent product of MASTERY FLIGHT TRAINING, INC.

Pursue Mastery of Flight™

This week’s LESSONS:

The Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) posted a new report this week:

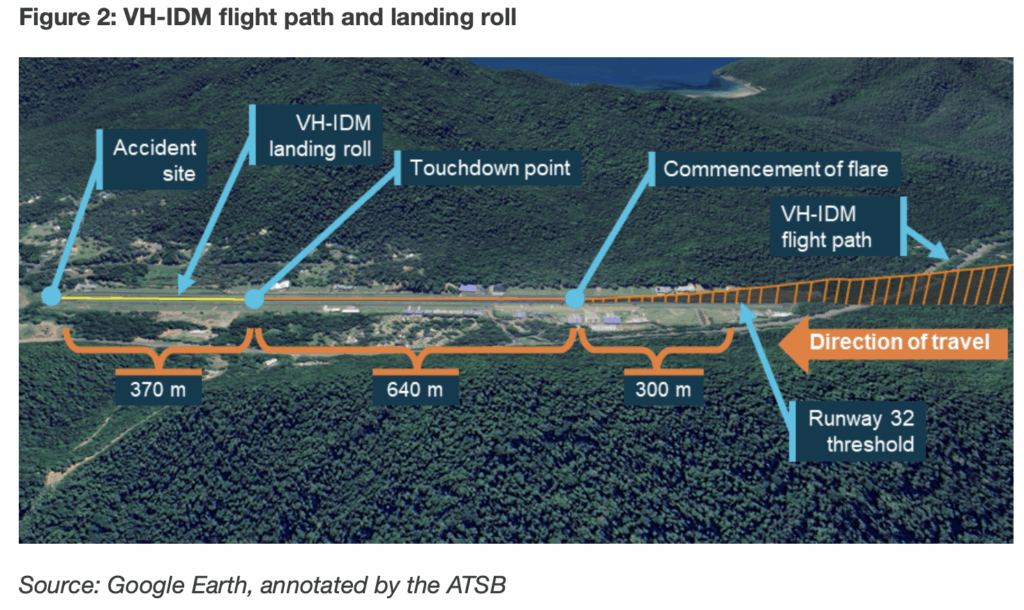

A GA8 Airvan operating a scenic flight in Queensland’s Whitsunday region overran the runway after the pilot did not initiate a go‑around when the aircraft was above profile with a high airspeed during approach, an ATSB investigation report details.

The aircraft, operated by Wave Air and with a pilot and seven passengers on board, was landing at Whitsunday Airport at Shute Harbour at the conclusion of a scenic flight on 2 November 2024.

After overrunning the runway, the Airvan travelled briefly across grass before entering marshy ground and coming to a stop in a ditch. While the aircraft was substantially damaged, the pilot and passengers were uninjured.

Australian investigators produce very useful, informative and timely reports. The final results were published in early May 2025 for an event that occurred in November 2024. I suppose there are far fewer aircraft and therefore far fewer investigations than in the U.S., so our Aussie friends have more and resources per accident time to delve into backgrounds and events leading up to a crash, permitting them to create a much fuller picture than their counterparts at NTSB.

Regardless, read the full report, including detailed, plain language paragraphs under each of these headings:

- What the ATSB found

- What has been done as a result

- The occurrence

Context:

- Pilot information

- Aircraft information

- Airport information

- Recorded data

- Weight and balance

- Pilot training

- Landing performance

Safety analysis:

- Pilot actions

- Training and assessment

- Safety issues and actions

- Findings

- Contributing factors

FLYING LESSONS-like, the ATSB adds these sections that show application of what was learned to other possible events to prevent repeating accident history, such as:

Safety message: Pilots should always be prepared to promptly execute a go-around if an approach for landing does not proceed as expected. Accurate knowledge of the aircraft’s reference speeds, in addition to having pre‑determined Stabilised approach criteria, assist the assessment of whether an approach should be discontinued. Furthermore, routine practice of this manoeuvre will ensure that it can be performed safely when needed.

Stabilised approach: The operator’s procedures specified that aircraft should be on a stabilized approach as early as practical on the final approach path and that the following criteria were required for an approach to be stable:

- the aircraft is on (or close to) the correct flight path, only small changes in heading and pitch being required to maintain that path

- the aircraft speed is not more than Vref + 20 kt and not less than Vref

- the aircraft is in the proper landing configuration (except that full flap should not be selected until committed to land)

- sink rate is maximum 1,000 ft/min

- power setting appropriate to the configuration but not below any minimum power for approach specified in the Aircraft Flight Manual

- all briefings and checklist items have been performed.

In visual conditions, if these criteria were exceeded below 100 ft above airport elevation, the pilot was required to execute a go‑around.

CASA provided guidance in AC 91‑02 on initiating go‑arounds in response to an unstable approach, stating that:

Pilot training stabilised that a safe landing is the result of a stabilised approach. If pre-determined stabilised approach criteria are exceeded, then a safe landing is not assured. The decision to execute a go-around should be made as early as possible to maximise the safety outcome. At the conclusion of an effective go-around, the pilot will then have an opportunity to consider what options are available to conclude the flight.

Additionally, the Flight Safety Australia article Quantifying the go-around* (CASA, 2021) highlighted the importance of practicing go‑arounds:

It’s not enough to pass the test and fly a go-around only every couple of years when tasked by an instructor. Consciously ask yourself if you’re in the slot, judging your aeroplane’s state and trend all the way down final. By quantifying your performance, you can make the go-around decision before you are at the highest risk of loss of control.

Going around is as natural a part of flying as landing itself – or it will be, if you evaluate landing criteria every time and occasionally practice the go-around task.

The pilot advised that, in addition to not considering a go‑around during this approach, they could not recall having previously conducted a go‑around outside of training.

*[Which, I’m proud to say, I wrote…something I didn’t notice in the report until I’d already been copying it into this week’s LESSONS – TT]

Related occurrences: The ATSB occurrence database contained 200 other reported occurrences of runway excursions during landing in Australia between January 2021 and December 2024. Of these, 12 resulted in injuries to the pilot and/or passengers, including 2 where the injuries were serious.

I’m in awe of the great work done by NTSB investigators given the time pressure and sheer number of aircraft accidents, all which meet certain threshold criteria must be investigated under Congressional mandate.

But to get much more detailed information about the factors contributing to an accident, to be able to turn them into even more information you can use to be an even safer pilot and/or instructor whatever and wherever you fly, subscribe to and read ATSB reports.

Questions? Comments? Supportable opinions? Let us know at [email protected].

Debrief

Readers write about previous LESSONS

Reader Tom Black writes about last week’s LESSONS about partial power loss in flight:

Training for partial power loss, while not common, is not new. I worked at Beech in Experimental Flight Test 1979-1981. I had the chance to fly with Ralph “Bud” Francis, chief test pilot, on several occasions and had many conversations with him. Bud was also a flight instructor, and when working with students he would give them partial and progressive power losses to deal with. His favorite was to decrease the maximum allowable manifold pressure by one inch every minute, simulating a slow progressive power loss. He said in his experience sudden complete power losses were rare but partial power losses and progressive power losses were more common and taxed the decision-making ability of a pilot more.

This was (according to Bud) because the situation initially would not appear too serious but would progressively deteriorate. It required making good decisions early in the scenario, becoming a test of the pilot’s ability to weigh information available and formulate an executable plan rather than simply responding by rote. Knowing the aircraft’s systems and how they work becomes an important element of that planning and execution, as does knowledge of available performance under different combinations of power and configuration (gear up or down, flap position, propeller RPM, drag due to items such as cowl flaps, etc.).

Training for partial power loss is something I was a proponent of long before my own experience last year of a minor but real partial power loss in cruise (intermittent engine roughness due to a fouled spark plug). We were within 12 miles of Chattanooga, so we diverted there to get the problem diagnosed and fixed. ATC gave us priority handling and things worked out beautifully. In retrospect, the only thing I would have done differently was rather than flying a normal approach I would have flown a simulated engine out overhead approach to allow for the possibility of things progressing to a complete engine failure in the pattern.

That’s an outstanding addition to the discussion and a great way to train pilots on The Region of Heightened Uncertainty. Thank you very much, Tom.

Reader/instructor and retired airline pilot John Whitehead adds:

Thoughts about partial engine failure:

- In the preflight brief, go over data that shows us partial failures are more common than total failures. There is minimal data because they often return safely. We just don’t think about it.

- Find a long runway to demo a liftoff followed by cutting the power and landing. Many don’t have an appreciation for how much runway it actually takes to return to the surface and stop. In the brief for this takeoff, discuss the pros and cons for landing gear down versus gear up [if flying a retractable gear aircraft].

- Set aside a training flight for an instrument departure that experiences a partial engine failure at some point shortly after takeoff. You either preset the navigator’s flight plan for a return approach to your origin or an approach to a nearby airport. How might you set that up on the navigator’s flight plan (to final destination as well as an emergency return) so the divert airport is readily available?

I had a partial failure on a nice VFR day. I was about three miles from the airport boundary such that I could turn back safely. What might the engine monitor look like? Do you have oil pressure? Will you continue to have oil pressure? With oil pressure, [a controllable pitch] propeller can be used as a speed brake …prop lever in/out as appropriate. Demo [this] on a training flight.

But when you finally lose oil pressure, the prop goes flat and becomes a giant speed brake. Since one can’t know when the loss of oil pressure might happen, it would be beneficial to fly a steeper than normal flight path to the runway. As creatures of habit, we are driven to the normal sight picture which is fine until we lose oil pressure on final followed by dropping like a rock. If one flies that steeper angle, this is where the use of the prop lever as a variable speed brake (assuming the engine never lost oil pressure) and/or employing a slip as a method to control flight path on short final. Overshooting the landing would be unfortunate after a mostly successful return to base.

Even more great insights. Thank you, John.

Reader/instructor Mike Dolan continues the discussion:

I would like to offer a small tip regarding partial power loss in [an] aircraft equipped with a carburetor. If the primer [valve] becomes unlocked and backs out it could cause such a problem. Yes, this is on the emergency check list but does the pilot have time to look at it? Sometimes yes, maybe not.

Through years of flight instruction, I have seen airplanes with spring loaded primers to prevent this, and even fuel injected engines with primers. This brings up the subject of “know thy aircraft before you fly.”

I agree. Further, this is why we need to read, practice and regularly review emergency procedures—so we know what things to do immediately when there’s not time to look at the checklist. As you say, “know thy aircraft.” Thanks, Mike.

Reader Boyd Spitler writes about the April 3 Mastery of Flight(R):

The “fit to fly” discussion calls to mind the need for compartmentalization in military aviation where “how I feel” is secondary to mission requirements. This sometimes applies to medivac work as well, but in no case is it appropriate for general aviation decision making. Training is a decisive factor.

That’s why I don’t like to use the term “mission” in private aviation, especially in public benefit flying. There are all too many cases in which pilots took risks “because the cancer patient was on board”, “the dogs need to be moved,” etc. In these cases we should be at least as conservative in our decision making as we are in our personal flying, because the nonflying public expects it of us. Thank you, Boyd.

Reader/instructor/accident investigator Jeff Edwards takes us back a week further:

Great piece as usual Tom. The discussion about the rationalization of overweight takeoffs was interesting. Rationalization like that is called the “normalization of deviance” in the safety world. It becomes a slippery slope often times where the margins get reduced to the point that there are no margins.

In my community of fliers the same holds true when discussing takeoff and landing distances. Since we are Experimental [category aircraft] we have no approved data so we recommend very conservative numbers. Of course we get pushback from pilots new to the fleet that want to land in a 2000 [foot] grass runway in a Lancair IVP. Yes you can do it once…but only once. Good margins are designed into our certified aircraft. We may not understand all the reasons behind them but we should respect them nonetheless.

Indeed we must. Thank you, Jeff.

And an anonymous but very insightful reader concludes:

Readers, what might be other basic rules for you? Do you have techniques that work for you? Have you ever had to make such a preflight decision? Did you make it, and if not, how did it come out?

Yes, it is near impossible to admit the “S” [stress] and “E” [emotion] of IMSAFE for one’s self. I truly believed I practice it but one day my CFI told me not to come back until “You have your head straightened out.”

I had received unwelcome news two days earlier that I had not yet been able to resolve that required immediate resolution. I had not slept well the night before the LESSON and, no surprise, my LESSON did not go well. After I rationalized my reason to my CFI he just looked at me and told me not to return until it was resolved.

That was a wake-up call that I failed the IMSAFE checklist.

Not sure if this will work, but I decided to implement another way of evaluating IMSAFE: Sometimes, after opening a can of soup or vegetables we sense something may be off and wonder. Rather than think about it, it goes straight into the trash. I trust whatever sense it is that made me question it.

Hopefully I will be able to use this for IMSAFE. If at any point the thought even enters my mind about flying, my decisions will be to cancel. Sure I can override my own rules, but why?

Anonymous, grateful reader!

I’m grateful as well. Thank you, anonymous.

More to say? Let us learn from you, at [email protected]

Share safer skies. Forward FLYING LESSONS to a friend.

Please help cover the ongoing costs of providing FLYING LESSONS through this secure PayPal donations link. Or send a check made out to Mastery Flight Training, Inc. at 247 Tiffany Street, Rose Hill, Kansas USA 67133. Thank you, generous supporters.

Thank you to our regular monthly financial contributors:

Steven Bernstein, Montclair, NJ. Robert Carhart, Jr., Odentown, MD. Greg Cohen, Gaithersburg, MD. John Collins, Martinsburg, WV. Dan Drew. Rob Finfrock, Rio Rancho, NM. Norman Gallagher. Bill Griffith, Indianapolis, IN. Steven Hefner, Corinth, MS; Ellen Herr, Ft Myers, FL. Erik Hoel, Redlands, CA. Ron Horton. David Karalunas, Anchorage, AK. Steve Kelly, Appleton, WI. Karl Kleiderer. Greg Long, Johnston, IA. Rick Lugash, Los Angeles, CA. Richard McCraw, Hinesburg, VT. David Ovad, Resiertown, MD. Steven Oxholm, Portsmouth, NH. Brian Schiff, Keller, TX. Paul Sergeant, Allen, TX. Paul Uhlig, Wichita, KS. Richard Whitney, Warrenton, VA. Jim Preston, Alexandria, VA. Johannes Ascherl, Munich, Germany. Bruce Dickerson, Asheville, NC. Edmund Braly, Norman, OK. Steven Hefner. Lorne Sheren, New Vernon, NJ. “The Proficient Pilot,” Keller, TX. Ed Stack, Prospect Heights, IL. Kynan Sturgiss, Hereford, TX. Bluegrass Rental Properties, LLC, London, KY. John Foster. Joseph Victor, Bellevue, WA. Chris Palmer, Irvine, CA. Barry Warner, Yakima, WA. Todd LeClair, Cadiz, KY

Thanks also to these donors in 2025:

John Teipen. N. Wendell Todd. David Peterson. Jay Apt. SABRIS Aviation/Dave Dewhirst. Gilbert Buettner. David Larsen, Peter Baron, Glen Yeldezian, Charles Waldrop, Ian O’Connell, Mark Sletten, Lucius Fleuchaus. Thomas Jaszewski. Lauren McGavran. Bruce Jacobsen, Leroy Atkins, Coyle Schwab, Michael Morrow, Lew Gage, Panatech Computer (Henry Fiorentini), John Whitehead, Andy Urban, Wayne Colburn, Stu Spindel, Dave Buetow, Ken Vernmar, Dave Wacker, Bill Farrell, David Miller

Pursue Mastery of Flight(R)

Thomas P. Turner, M.S. Aviation Safety

Flight Instructor Hall of Fame Inductee

2021 Jack Eggspuehler Service Award winner

2010 National FAA Safety Team Representative of the Year

2008 FAA Central Region CFI of the Year

FLYING LESSONS is ©2025 Mastery Flight Training, Inc. For more information see www.thomaspturner.com. For reprint permission or other questions contact [email protected].