Topics this week include: > Early Analysis > Approach category > The spirit of the rule

FLYING LESSONS uses recent mishap reports to consider what might have contributed to accidents, so you can make better decisions if you face similar circumstances. In most cases design characteristics of a specific airplane have little direct bearing on the possible causes of aircraft accidents—but knowing how your airplane’s systems respond can make the difference in your success as the scenario unfolds. So apply these FLYING LESSONS to the specific airplane you fly. Verify all technical information before applying it to your aircraft or operation, with manufacturers’ data and recommendations taking precedence. You are pilot in command and are ultimately responsible for the decisions you make.

FLYING LESSONS is an independent product of MASTERY FLIGHT TRAINING, INC.

Pursue Mastery of Flight®

This week’s LESSONS:

The crash of a privately operated, single-pilot Cessna Citation II jet into a military housing area in the wee hours of the morning of May 22 received significant press both in aviation and mainstream markets. Six aboard the jet died in the crash and there was extensive damage to houses and cars in the airplane’s final, explosive path.

Several subject matter experts have posted their views on the crash with what’s known so far. Best among them (in my opinion) is the Early Analysis done by AOPA Air Safety Institute’s Mike Ginter. I think it’s best because Mike dispassionately lays out the facts and some general considerations suggested by initial reports—the same sort of thing I try to do in FLYING LESSONS Weekly. If you’ve not yet seen a preliminary review of this crash and you’re interested, or if you’ve watched analyses that are strong on causation and judgement, watch the 10 minute ASI program.

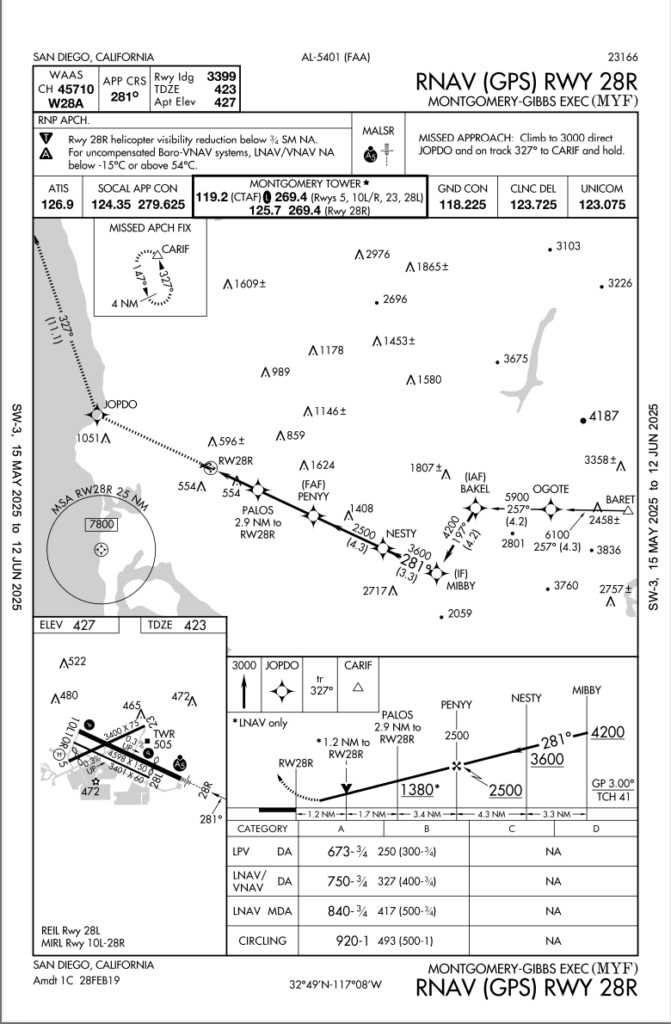

The flight appeared to be very precisely following the approach—“stabilized” and “on rails,” as Ginter puts it—up to the Final Approach Fix. The FAF is where glidepath intercept occurs and the final descent begins. In this case the FAF is 6.3 miles from the runway threshold and the airplane was, and should be, at 2500 feet above Mean Sea Level, or 2077 feet above the runway touchdown zone elevation. That’s a bit higher than a typical glidepath/glideslope intercept, but also over a mile further away than typical, resulting in the standard three-degree descent gradient.

As Ginter notes, the Citation appears to have been very precise, up to the FAF. But by the next fix on the approach, PALOS, the jet was about 180 feet below glidepath. It continued to descend below glidepath until impacting power lines about 50 feet below their charted height of 554 feet MSL. The vertical speed (not specifically mentioned) was greater than required to maintain glidepath at the aircraft’s current ground speed.

The was a lot working against the safe completion of this flight. It had flown overnight more than seven hours across the entire country with a quick, middle-of-the-night fuel stop at my home airport at Wichita, Kansas. The pilot may have been working all day up to the late evening departure from Teterboro, New Jersey, according to online comments. The weather reporting system at the destination airport was inoperative and nearby airports reported conditions below minimums for the approach being flown. A NOTAM reported inoperative instrument approach lights.

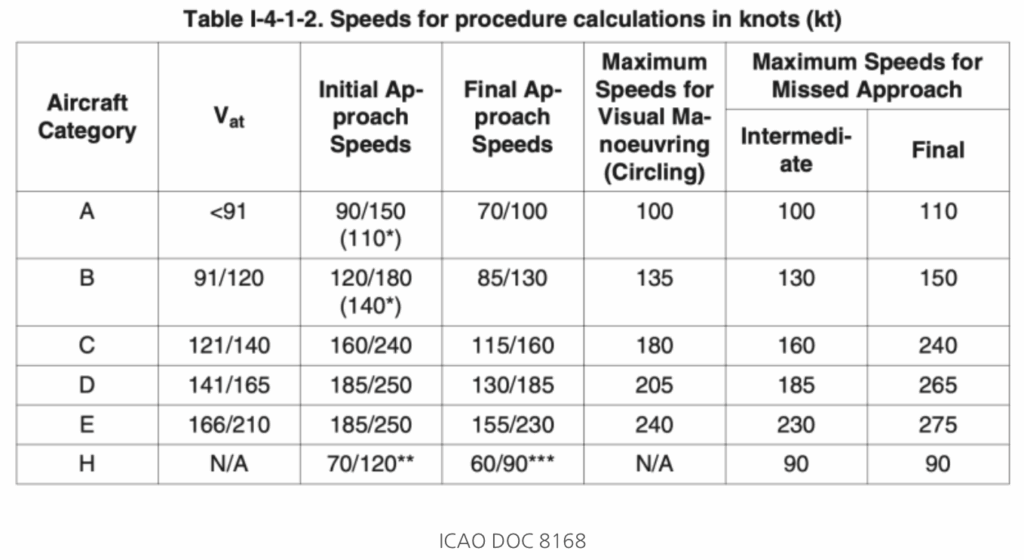

I really can’t add to ASI’s Early Analysis except for one additional item not reported there or anywhere else I’ve seen for that matter: Approach category. Online sources state the Citation II is a Category C airplane. Some pilots report it may be flown Category B. Ginter’s analysis states the airplane was flying “120 to 125 knots, a little fast.” That would put the jet in Category C for the approach as flown. The RNAV (GPS) 28R approach chart includes that minimums are “NA”—Not Authorized—for Category C and D airplanes.

That leads us to this week’s LESSON: a review of the sometimes-misunderstood Approach Category requirements.

In 2023 the FAA published Information for Operators (InFO) letter 23001, Use of Aircraft Approach Category During Instrument Approach Operations. This letter replaces some previous guidance and clarifies regulatory and other advisory guidance to reinforce the rules of approach categories. The InFO states:

Aircraft approach category is…based on a VREF (reference landing speed), if specified, or if VREF is not specified, 1.3 VS0 (stalling speed or minimum steady flight speed in the landing configuration), both at the maximum certificated landing weight…. An aircraft’s approach category does not change if the actual landing weight is less than the maximum… [and is] permanent and independent of the changing conditions of day-to-day operations. Aircraft may not be flown to the instrument approach minima of a slower approach category…. If it becomes necessary to operate at a speed in excess of the upper limit of the speed range of an approach category, the minimums of the higher category should be used if available…. Pilots are responsible for determining when a higher approach category applies.

See the InFO for full details.

The language of the InFO does not make using a higher category mandatory, using terms like “should” instead of “must” be used, and including the qualifier “if available.” It’s “the pilot’s responsibility,” as the InFO states, to determine which minima apply. Although the “letter” of the law is that the higher category is recommended but not required, I feel the spirit of the rule implores pilots to use the approach category for the speed at which they are flying. In the case of the accident Citation jet that would imply the approach is not authorized, and should not be flown, at faster than 120 knots…the top of Category B.

That’s yet one more red flag in addition to those pointed out in ASI’s Early Analysis that should cause a pilot to rethink flying that approach under those conditions…or attempting that back-of-the-clock literal cross-country flight under those circumstances at all. Would this have made any difference in the Citation crash? Other than convincing the pilot he should not have attempted the approach at all, probably not. The answer probably resides in why the aircraft descended more steeply than the published glidepath until it hit the overhead lines and plunged into the houses below. It takes time for the investigators do their work.

Regardless this tragedy is a good reminder to consider the regulation—and the safety intent—of approach category, and how it is one factor on deciding whether and how to fly an approach.

Questions? Comments? Supportable opinions? Let us know at [email protected].

Debrief

Readers write about recent LESSONS:

Several readers added to last week’s discussion of techniques for avoiding minor but costly accidents. Jim Piper writes:

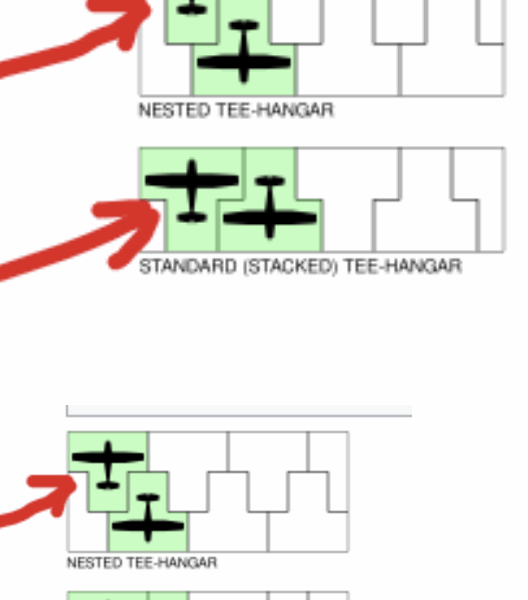

All good advice for sure! I would further add that if wingtip clearance is tight or marginal in one’s hanger, a main wheel and a nose wheel guide line painted on the ramp surface leading to the hanger door threshold can be very helpful. Masking tape also works well on hangar floors in lieu of paint.

Jason Robertson adds:

When pushing a plane into the hangar, you suggested “Paint an alignment stripe on the hangar floorfrom the door opening to where the nose (or tail) wheel should end up. If the hangar owner frowns on paint try children’s colored sidewalk chalk, remarking it monthly or as needed.”

This might work with a taildragger, but it doesn’t work very well with tricycle landing gear. With tricycle gear, even with the nose wheel right on the line the plane can veer far to the left or right. Years ago, a hangar mate suggested a much better alternative. In addition to the line on the ground for the nose wheel, paint a vertical line on the wall behind the vertical stabilizer. If you start with nose wheel on its line, you only need to keep the vertical stabilizer aligned with the vertical line on the wall as you push the plane in. It gives you much better feedback than line(s) on the ground and guides the plane into position better. It’s kind of like centering a VOR needle, you make constant, small corrections. If you don’t want to paint on the wall, put a strip of tape on the wall instead.

Richard McGinnis agrees:

With some aircraft, in a topical tight stack tee hangar, it is possible to have both the main gear tires and the nose tire on floor strips and still have the horizontal tail hit the forward side of the tee to the next hangar. Stripes on the back wall to align the vertical tail are also necessary to avoid a horizontal tail strike. Monitoring three floor stripes and a strip on the back wall are required when moving the aircraft into the hangar.

As does Mark Travis:

Paint an alignment stripe for one of the main gear! Not the nosewheel. The airplane can shift an amazing amount right or left of the centerline while the nose wheel happily stays planted on the stripe. A main gear stripe will ALWAYS put the plane on the exact desired trajectory.

I painted a 15 foot stripe for the right main gear to my Bonanza and Baron and NEVER got close to an incident. Of course, I always fully opened the hangar doors first. With a 38’ wingspan and a 40’ hangar width, you learn to be very precise.

John Dale suggests a solution to tow bar strikes:

I finally fixed the problem. I now have three different taildraggers in my hangar. All have wooden props and the towbars are at the other end of the aircraft!

Some readers sent in hangar scenarios, including this from Chuck Davis:

I’ve been flying since 1979 and it sure is interesting how many ways you can invent to ding an airplane on the ground. Years ago some guys here at work arrived home after dark from a trip in our company G58 [Baron]. While pushing the plane slightly uphill into the hangar, an inexperienced employee pushed too hard on the left wing tip (just trying to be useful) and slewed the plane in the hangar resulting in the right elevator tagging the hangar column. Beech had just shifted production of that [component] to Mexico and they were making them out of aluminum skin instead of the original magnesium material. It took about three months and $25,000 to correct that little boo boo. The plane flew on with a hybrid elevator skin [original magnesium on one elevator, aluminum on the other, which is perfectly FAA-acceptable—tt]. When we sold the airplane years later, the buyer hammered us on the damage history to get us to reduce the sale price. Ouch 1 and Ouch 2.

Here’s another one: Several years ago I pushed my 2013 Super Decathlon out of the hangar to get fueled up. For whatever stupid reason, I got out of my preflight routine and got in the airplane, belted up, cranked up and started to taxi. It took more power than usual to get rolling and I thought, “What the heck is going on?” It occurred to me that I left my Taildragger Dragger dolly attached to the tailwheel. I shut down and got out expecting disaster. But luckily, and I mean luckily, no damage was done to the elevator. Now I do exactly what you advised: attach and detach the tow bar ONLY when moving the plane. PERIOD!

Here’s my last one: My airplane is kept in an enclosed metal hangar with horizontally sliding doors. There are six total hangars adjacent to one another on my side of the building. I am at the end of the building so both of my doors slide open to the south. When the next-door neighbor opens his north half-door it completely blocks mine and there is no chance of impact. I like to store my plane asymmetrically in the hanger with about 2 foot of right wingtip clearance to open up working room on the opposite side of the hangar. I got schooled recently when the second door down neighbor pulled his Arrow out of his hangar. My two doors were fully open to the south as I went up for a flight. When the gentleman in the third hangar opened his half-door to the north, it was meant to stop flush with the end of my door. However, he shoved mine north a couple feet to make room for his hands, I guess. Later on as I was pulling my plane up into the hangar with my Taildragger Dragger, I fortunately looked to the right and saw my door closed by that amount just before I smacked it.

I have been in and out of that hangar hundreds of times. Thinking about the what-ifs had I hit that door with the trailing edge of my aileron makes me almost sick. Now, without exception, every time I move my plane in or out, I am on high alert.

Thanks for the article. Every detail matters!

Fred Rogge adds:

When I first got my CFI I went to work for an FBO / Flight School that had a large maintenance hangar. The FBO was a Cessna dealer and a Cessna Flight Center. They had everything from a C152 to a C402 in their fleet. The hangar had a single bi-fold door that had markings on the sides of the door frame. They were lines that also had the type of aircraft next to the lines. When the hangar door was opened to move an airplane in or out, we had to open (raise) the bi-fold door until the bottom of the door was above the line for the type of airplane being moved. It was also the FBO’s policy that if an airplane being moved was not one of the company owned airplanes that the door was required to be raised all the way to the top of the door frame. This setup was one of the best I’ve ever seen and we never had any “hangar rash” damage to any of the aircraft.

From Laurie McGavran:

We use your suggestions 3 and 4 about the chocks and the painted stripe(s). They are very useful for parking the airplane square and in its place.

We leave the towbar attached in the hangar. Nobody is going to start the engine in the hangar and you need the towbar to move the plane, so it isn’t going to be forgotten. In every other case, we remove the towbar as soon as we are done moving the plane.

In the same vein of not leaving things out, I never put down a fuel cap. If I need to set it down, I put it back in place.

We have side opening hangar doors where the outer two doors swing out. We often leave the hangar open when we go out if the wind is calm. Once, one of the doors had gotten shut partway while we were out. We bumped the door as we pushed the plane back. No damage – we weren’t going that fast. Make sure the doors are open even if you left them that way. I taxied into one of the side doors. I’d pulled the plane out but had turned it close enough in that it didn’t clear the door. No door damage; damage to the wingtip and nav light. It was not too expensive to get a new wingtip and have it installed and the light fixed. I didn’t claim insurance.

Embarrassingly, I almost let the plane-pusher [powered towbar] drive the airplane into the doors. We have an old pusher that needs to be plugged in, and we use a trouble light as an additional extension cord. I had gotten everything set up and flipped the switch on the pusher and nothing happened. So I went back and turned on the light. (Duh!) But I hadn’t turned off the switch to the pusher. The plane began slowly creeping towards me and the hangar. I thought it was rolling and tried to stop it. No luck. Then I realized what happened and ran to turn off the power. Got there just in time! I don’t know that there is any good way to make sure that doesn’t happen again, except to remember the lesson well.

I also had a plane start rolling when I was fueling. I had apparently leaned against the wing as I was fueling. My partner was there and stopped the plane. The lesson here is to chock it or set the brake, even on very level surfaces. And, oh, yes. Don’t pull the fuel hose while you are on the ladder; you might get pulled backwards off the ladder. Almost happened to me. Make sure there’s plenty of hose pulled out.

I guess I’m lucky that these were “almost happened” or “little to no damage” lessons!

Thank you, everyone, for your added techniques, experiences and discussion.

More to say? Let us learn from you, at [email protected]

Share safer skies. Forward FLYING LESSONS to a friend.

Please help cover the ongoing costs of providing FLYING LESSONS through this secure PayPal donations link. Or send a check made out to Mastery Flight Training, Inc. at 247 Tiffany Street, Rose Hill, Kansas USA 67133. Thank you, generous supporters.

Thank you to our regular monthly financial contributors:

Steven Bernstein, Montclair, NJ. Robert Carhart, Jr., Odentown, MD. Greg Cohen, Gaithersburg, MD. John Collins, Martinsburg, WV. Dan Drew. Rob Finfrock, Rio Rancho, NM. Norman Gallagher. Bill Griffith, Indianapolis, IN. Steven Hefner, Corinth, MS; Ellen Herr, Ft Myers, FL. Erik Hoel, Redlands, CA. Ron Horton. David Karalunas, Anchorage, AK. Steve Kelly, Appleton, WI. Karl Kleiderer. Greg Long, Johnston, IA. Rick Lugash, Los Angeles, CA. Richard McCraw, Hinesburg, VT. David Ovad, Resiertown, MD. Steven Oxholm, Portsmouth, NH. Brian Schiff, Keller, TX. Paul Sergeant, Allen, TX. Paul Uhlig, Wichita, KS. Richard Whitney, Warrenton, VA. Jim Preston, Alexandria, VA. Johannes Ascherl, Munich, Germany. Bruce Dickerson, Asheville, NC. Edmund Braly, Norman, OK. Steven Hefner. Lorne Sheren, New Vernon, NJ. “The Proficient Pilot,” Keller, TX. Ed Stack, Prospect Heights, IL. Kynan Sturgiss, Hereford, TX. Bluegrass Rental Properties, LLC, London, KY. John Foster. Joseph Victor, Bellevue, WA. Chris Palmer, Irvine, CA. Barry Warner, Yakima, WA. Todd LeClair, Cadiz, KY

NEW THIS WEEK: Jim Hopp, San Carlos, CA. Adrian Chapman, West Chester, PA

Thanks also to these donors in 2025:

John Teipen. N. Wendell Todd. David Peterson. Jay Apt. SABRIS Aviation/Dave Dewhirst. Gilbert Buettner. David Larsen, Peter Baron, Glen Yeldezian, Charles Waldrop, Ian O’Connell, Mark Sletten, Lucius Fleuchaus. Thomas Jaszewski. Lauren McGavran. Bruce Jacobsen, Leroy Atkins, Coyle Schwab, Michael Morrow, Lew Gage, Panatech Computer (Henry Fiorentini), John Whitehead, Andy Urban, Wayne Colburn, Stu Spindel, Dave Buetow, Ken Vernmar, Dave Wacker, Bill Farrell, David Miller, Daniel Norris, Robert Sparks

NEW THIS WEEK: Bill Cannon

Pursue Mastery of Flight(R)

Thomas P. Turner, M.S. Aviation Safety

Flight Instructor Hall of Fame Inductee

2021 Jack Eggspuehler Service Award winner

2010 National FAA Safety Team Representative of the Year

2008 FAA Central Region CFI of the Year

FLYING LESSONS is ©2025 Mastery Flight Training, Inc. For more information see www.thomaspturner.com. For reprint permission or other questions contact [email protected].