FLYING LESSONS uses recent mishap reports to consider what might have contributed to accidents, so you can make better decisions if you face similar circumstances. In most cases design characteristics of a specific airplane have little direct bearing on the possible causes of aircraft accidents—but knowing how your airplane’s systems respond can make the difference in your success as the scenario unfolds. So apply these FLYING LESSONS to the specific airplane you fly. Verify all technical information before applying it to your aircraft or operation, with manufacturers’ data and recommendations taking precedence. You are pilot in command and are ultimately responsible for the decisions you make.

FLYING LESSONS is an independent product of MASTERY FLIGHT TRAINING, INC.

Pursue Mastery of Flight™

This week’s LESSONS

Pilot Reversionary Mode

“You will perform at or just below your everyday standard under stress.”

—Dr. Tony Kern, Col USAF (ret.), Convergent Technologies, Inc. 2017

“We don’t rise to the level of our expectations, we fall to the level of our training.”

–Archilochus, lyric poet (i.e., historian), 4th century BC Greece

“Partial panel” isn’t what it used to be. In glass cockpit airplanes, a still-small but rapidly growing percentage of general aviation aircraft, there are often multiple screens and, at times, completely redundant Attitude/Heading Reference Systems (AHRS). Multiscreen installations usually have the capability of entering a reversionary mode if the primary screen fails for some reason but AHRS data is still available. Sometimes automatically, available manually, in the reversionary mode the required flight and some navigation and monitoring functions (traffic alerts, engine data, etc.) may transfer to an alternate screen.

In reversionary mode the pilot still has more information for precision flight, situational awareness and hazard avoidance than most pilots—including airline and military—have had for the entire history of flight. Flying “partial panel” this way takes a little practice to alter your scan, but it does very little to reduce your ability to fly.

Pilots have a type of reversionary mode, too. Unlike digital avionics, however, in our case the reversionary mode can severely limit our ability to function. Avionics enter reversionary mode when systems fail and data is not presented in the form of visual information. Pilots enter reversionary mode when workload commands our attention and tasks our ability to process all the information and data coming at us. Like the glass panel that sheds some capabilities to stay within its diminished bandwidth, we too will stop doing some things when we can no longer do them all. The trouble is, we do not have an automated logic for deciding which things we’ll stop doing—we just start missing things.

Let me give you an example. If you are not instrument rated or not familiar with U.S. IFR procedures please bear with me; I’ll try to make at least the key points clear to everyone.

Several years ago I took an Instrument Proficiency Check (IPC) with FLYING LESSONS reader Chris Hope, who was the 2015 National FAA Safety Team Representative of the Year. I flew up to Chris’ home base in the Kansas City, Missouri area for my IPC flight. I knew Chris would give me a good workout, to test my abilities and let me learn from the experience. He did not disappoint.

Without going into too much detail, we departed Lee’s Summit (KLXT, index 1 on the map), simulating takeoff into instrument conditions in vectors to Midwest National Airport (KGPH, index 2).

Chris gave me headings to simulate radar vectors in the clear, cold and very turbulent low-level air. I was throttled back to remain below Turbulent Air Penetration Speed; that speed reduction and the strong northerly wind aloft (despite winds at the surface favoring the south runway), we were only getting about 125 knots ground speed.

We intercepted KGPH’s ILS Runway 18, turning inbound initially with a strong tailwind. I voiced that we would probably have to descend at 700 feet per minute or more (as opposed to the normal 500-600 fpm) because of the high ground speed southbound. But quickly the wind changed; we bounced through the wind shear that accompanied the shift, and as it turned out a normal descent kept us on the glideslope.

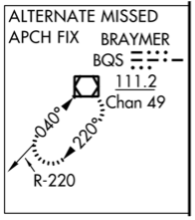

The published missed approach procedure includes a route toward the Napoleon VOR (ANX, index 3), and a holding pattern there. However, my preflight planning revealed that ANX was temporarily out of service. A NOTAM on the ILS 18 approach directed that the alternate missed approach procedure was in effect. Unusually, an alternate missed is printed on the approach chart: an initial climb south and then a turn northeast, in a long (as I recall, about 24 mile) trek toward the Braymer VOR (BQS).

During my approach briefing, which I do aloud whether or not I have an instructor on board, I stated another unusual situation: Although the standard missed approach procedure is included in the GPS database and available to provide navigation guidance to me (or the autopilot) at the touch of the SUSPEND button after beginning my climbout, the alternate missed is not. If I had to fly the missed approach procedure (a good bet on an IPC), I would have to manually navigate to the Braymer VOR and in the hold. I set up the #2 VOR to navigate to BQS “old school.”

Once I began the missed and was tracking the VOR toward BQS, I programmed “Direct To” BQS in the GPS. When I crossed the fix and began entering the hold, I used the GPS’ OBS (omnibearing selector) mode to plot a line that corresponded to the hold’s inbound course. The hold itself did not appear on the GPS map page. (Note: more recently available GPS devices may offer the ability to create your own holding pattern. I was flying with a non-WAAS Garmin 530 at the time).

After the hold Chris instructed me to go direct to a point southeast of the Lee’s Summit airport that is the Initial Approach Fix (IAF) for an RNAV (GPS) approach. As soon as I was enroute he simulated attitude and heading indicator failure (redundant systems in this particular airplane, but I’m game for a training challenge). So there I was, partial panel, no autopilot available, under the hood, in continuous light and occasional moderate turbulence, using the GPS NAV 1 page and a terribly bouncy magnetic compass for heading …when he pulled the landing gear motor circuit breaker. Asking simulated “Air Traffic Control” (Chris) for an extended hold at the IAF, I cranked the gear down by hand in the hold, hand-flying partial panel in turbulence while wearing my favorite view limiting device (check that, no view limiting device can be a “favorite”). Then I flew the circle-to-land approach into KLXT.

That’s a whole lot to have happen in a short time. And that’s the point. You see, I’m pretty good with checklists. I’m not a slave to them—I use cockpit flows and practiced procedures, but then use a printed checklist to confirm I’ve not missed anything. I was on my best checklists-and-flows behavior on this flight. Before Start, Starting, Taxi, Before Takeoff, Takeoff, Climb, Level-Off, Descent, Approach, I was doing them all.

But when workload got very high, the checklist was the first thing I let go. I was almost at the hold at Braymer before I remembered to consult the Climb and Level-Off checklists after my missed. Later, I skipped the Approach checklist because I was just too busy hand-flying, real old-style partial panel. I did use the manual landing gear extension checklist in the holding pattern.

That’s when I remembered what Tony Kern had said at the Bombardier Safety Standdown I’d attended about a month before. I was still commanding the airplane…but under stress, I was operating a little below my normal level of performance. I didn’t rise to the occasion, I fell to the level of my training…and then some.

Taking a drink from a bottle of water in the copilot’s seat-back pocket because I was by then very dehydrated, I fixed the situation by taking a breath, shaking out the cramp in my gear-extension arm, and then…pulling out the Approach checklist to get myself back in the flow, working back up to my usual performance level.

The workload of simulated systems failures in IMC put me in the pilot reversionary mode. I work hard to maintain my skills. On that day under that workload I was good enough, even though I was below my usual performance level (I earned my IPC endorsement). To get back up to speed I had to force myself to get back to basics—fly the airplane, get ready for the approach, and consult the checklist to make up for any lapses my reversionary state created.

On a bad day you still need to be very, very good. Is your “normal” good enough that, even when things get busy and you operate below your peak performance, that you are still able to fly precisely and to the standards of your certificates and ratings, while dealing with unusual status and potentially emergency situations?

Questions? Comments? Supportable opinions? Let us know at [email protected]t.

Debrief

Readers write about recent FLYING LESSONS:

Reader and well-known Australian flight instructor Edgar Bassingthwaighte writes about last week’s LESSONS:

Thanks for a good commentary on touch and goes, particularly for retractables.

The point on “loss of control on the runway during the low-speed portion of rollout” would be correct for tailwheel aircraft but I would say that the greater risk for tricycle gear aircraft is excess speed on touchdown. Putting the aircraft down with excess speed transfers weight to the nosewheel which makes it very easy to lose directional control – akin to a tailwheel aircraft on steroids you might say.

Most categorize that sort of runway event as a hard landing but I see your point. Not exclusively by any stretch, but especially in airplanes with free-castoring nose wheels (such as the Cirrus) this is especially true. It goes to my earlier writings that it is perhaps somewhat better to be a little fast than to be low on approach, but it’s important to be at the correct speed for approach and landing—not too slow, but not too fast either. Thank you, Edgar.

Reader, pilot examiner and test pilot Dale Bleakney adds:

As always, a great article and I like your discussion on touch and go landings. I would like to throw a wrinkle in the there for your CFI listeners to think about. First discussion: Short field takeoffs:

An additional benefit of a “stop and go,” not touch and go, is the following scenario: I will ask students on Private or Commercial checkrides to land on a runway and come to a complete stop. I make sure that the runway is long enough to safely complete a stop and go and yet short enough to ensure that they will gain confidence in their takeoff distance calculation, if flown properly. Often this is the first time that a student has ever tried to conduct a takeoff with less than full runway length and where they need to trust their calculation. I always have at least 50% or more margin. This may be something instructors want to explore.

Second discussion item: Short field landings:

I have had a number of students come to me and have never done or done very few short field landings using a 50 foot obstacle at the end of the runway. Putting this obstacle some distance before the threshold doesn’t count (in my opinion). CFIs need to continue to teach the obstacle as it is still in the ACS [Airman Certification Standards] at the DPE’s [Designated Pilot Examiner’s] discretion (see the ACS appendix).

From a practical standpoint, the purpose of the short takeoff and landing practice is to learn techniques that emulate how the book performance was obtained. I don’t expect students to get book performance, but it would be nice to see something close.

Side note: On landings, stating that they will hit the 1000-foot marker is not a short field landing. That is a power on accuracy landing. I know some DPEs will accept this, but I prefer to see the short field landing performed the way that the performance data is shown in the POH. The touchdown point should be the difference between the total distance and ground roll. Only in rare instances does that work out to be 1000 feet down the runway. On a Cessna 172, that point is about 700-750 feet down the runway.

Third discussion item: Stalls:

Entry rate: Students are entering stalls at too high of an entry rate. These should be trained at approximately 1 knot/second entry rate [of deceleration]. Most students just keep pulling at a pitch rate and don’t even look at the airspeed rate. I think if they learn to slow the airspeed entry rate down, they will get better stall characteristics, the stalls can become less scary for students, and it better emulates what will happen in a real-life inadvertent stall. 3-5 kt/s is actually an accelerated stall.

On check rides, I always ask for stalls in a turn. The Airman Certification Standards allows examiners to ask for the stalls in a turn (at the DPE’s discretion). I have recently seen multiple applicants who have never done one in a turn (or at least that is what they state). I think that stalls in turns are more realistic and again, are when the stall might be more likely to occur. The ACS states that the turn should be at 20° +/- 10° bank. I don’t know what other DPEs are asking for, but I always specify these in a turn.

Power-on stall power setting: During the certification process, the manufacturer is allowed to do power-on stalls at 75% power if the pitch attitude of the airplane exceeds 30°. I have seen students in 172s reducing power on these stalls and quoting this certification relief. First, in order to take this relief, the 30° pitch attitude has to occur using the following entry: starting at 1.5 Vs1 and decelerating at 1 kt/s until pitch break or deterrent buffet. In most light airplanes the 30° pitch attitude will not be exceeded at full power. Also, the relief only allows the reduction to 75% power. At the altitudes and density altitudes where stalls are done, 75% power is full power or really close to it. I argue that I can get to 30° pitch attitude in a glider if I enter at the wrong speed (too fast) and decrease airspeed too quickly (more the 1 kt/s).

As always, I think what you do makes a significant impact on the safety of the flying community. Thank you.

Thank you, Dale, for sharing your significant insights.

More to say? Let us learn from you, at [email protected].

NAFI Summit Encore Recorded Presentation:

Tom Turner on Presenting Effective and Meaningful Flight Reviews

Thursday, May 16, 2024 at 19:00 Central Daylight Time (17:00 PDT; 18:00 MDT; 20:00 EDT; 14:00 HST; 16:00 AKDT; 17:00 Arizona; Friday, May 17, 2024 00:00 GMT)

Select Number:

CE03130135

Description:

This presentation outlines a number of ways a Flight Review can be used to check and improve a pilot’s knowledge and skills. This outline is a guide to help CFIs and pilots work together for a more effective flight review experience.

To view further details and registration information for this webinar, click here.

The sponsor for this seminar is: FAASTeam

The following credit(s) are available for the WINGS/AMT Programs: Master Knowledge 2 – 1 Credit

Click here to view the WINGS help page

Share safer skies. Forward FLYING LESSONS to a friend

Please help cover the ongoing costs of providing FLYING LESSONS through this

secure PayPal donations link. Or send a check made out to Mastery Flight Training, Inc. at 247 Tiffany Street, Rose Hill, Kansas USA 67133. Thank you, generous supporters.

Thank you to our regular monthly financial contributors:

Steven Bernstein, Montclair, NJ. Robert Carhart, Jr., Odentown, MD. Randy Carmichael, Kissimmee, FL. Greg Cohen, Gaithersburg, MD. John Collins, Martinsburg, WV. Paul Damiano, Port Orange, FL. Dan Drew. Rob Finfrock, Rio Rancho, NM. Norman Gallagher. Bill Griffith, Indianapolis, IN. Steven Hefner, Corinth, MS; Ellen Herr, Ft Myers, FL. Erik Hoel, Redlands, CA. Ron Horton. Robert Hoffman, Sanders, KY. David Karalunas, Anchorage, AK. Steve Kelly, Appleton, WI. Karl Kleiderer. Greg Long, Johnston, IA. Rick Lugash, Los Angeles, CA. Richard McCraw, Hinesburg, VT. David Ovad, Resiertown, MD. Steven Oxholm, Portsmouth, NH. Brian Schiff, Keller, TX. Paul Sergeant, Allen, TX. Ed Stack, Prospect Heights, IL; Paul Uhlig, Wichita, KS. Richard Whitney, Warrenton, VA. Jim Preston, Alexandria, VA. Johannes Ascherl, Munich, Germany. Bruce Dickerson, Asheville, NC. Edmund Braly, Norman, OK. Steven Hefner. Bruce Douglass, Conway, MA

NEW THIS WEEK: Lorne Sheren, New Vernon, NJ

And thanks to these donors in 2024:

Jim Lara, Joseph Stadelmann, Dixon Smith, Barry Warner, Wayne Mudge, Joseph Vandenbosch, Ian Campbell, Jay Apt, John Kimmons, Derek Rowan, Michael Maya Charles, Ron Horton, Lauren McGavran, Gerald Magnoni, Amy Haig, Rod Partlo, Brent Chidsey, Mard Sasaki-Scanlon, SABRIS Aviation (Dave Dewhirst), Edmund Braly, Joseph Orlando, Charles Lloyd, Michael Morrow, Abigail Dang, Thomas Jaszewski Danny Kao, Gary Garavaglia, Brian Larky, Glenn Yeldezian, David Yost, Charles Waldrop, Robert Lough

NEW THIS WEEK: Gilbert Buettner

Pursue Mastery of Flight

Thomas P. Turner, M.S. Aviation Safety

Flight Instructor Hall of Fame Inductee

2021 Jack Eggspuehler Service Award winner

2010 National FAA Safety Team Representative of the Year

2008 FAA Central Region CFI of the Year

FLYING LESSONS is ©2024 Mastery Flight Training, Inc. For more information see www.thomaspturner.com. For reprint permission or other questions contact [email protected].