FLYING LESSONS uses recent mishap reports to consider what might have contributed to accidents, so you can make better decisions if you face similar circumstances. In most cases design characteristics of a specific airplane have little direct bearing on the possible causes of aircraft accidents—but knowing how your airplane’s systems respond can make the difference in your success as the scenario unfolds. So apply these FLYING LESSONS to the specific airplane you fly. Verify all technical information before applying it to your aircraft or operation, with manufacturers’ data and recommendations taking precedence. You are pilot in command and are ultimately responsible for the decisions you make.

FLYING LESSONS is an independent product of MASTERY FLIGHT TRAINING, INC.

Pursue Mastery of Flight™

This week’s LESSONS:

Let’s catch up on your excellent comments and insights by “going direct” to the Debrief.

Questions? Comments? Supportable opinions? Let us know at [email protected].

Thank you to my friends at Pilot Workshops for renewing their annual sponsorship of FLYING LESSONS

Debrief:

Readers write about recent FLYING LESSONS

Reader Jim Piper writes about last week’s LESSONS:

Tom, the accident report doesn’t state what time of year the flight was flown. If it was during winter months the possibility of temperatures conducive to icing certainly should have been considered by the pilot although your narrative sounds as though he didn’t consider much at all! That kind of complacency is hard to imagine.

I know there are many who will disagree but I feel that night flight, and particularly night flight into mountainous terrain in a single engine aircraft is at the very least foolish and possibly borderline suicidal. It should probably be conducted under instrument flight rules and if that is not practical (airways, MEAs etc.) or legally possible (non instrument rated pilot) it should only be attempted in day VMC.

I did not copy the date in the excerpt I published last week, but following the link I provided to the NTSB Probable Cause report will tell you the night icing encounter occurred on January 15, 2018…making the pilot’s NTSB-reported complacency about weather briefing as baffling to me as it is to you, single-engine or twin, piston engine or turbine. Thank you, Jim.

Reader, instructor, Air Safety Investigator, aero-academic and friend Jeff Edwards continues:

This type of accident has been the subject of my research interest for a long time. AOPA did a survey years ago and found that 70% of instrument rated GA pilots were not current. Some pilots view an instrument rating as an “insurance policy” in case they need to get through some weather to complete the flight. These pilots are often not current or even close to proficient. With the proliferation of autopilots in GA, the pilots rely on George to do the flying in IMC. The outcome is often tragic. For more information: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/jate/vol4/iss1/5/

Sobering statistic. Thank you, Jeff, for the link to your research.

Regarding the May 23 Debrief about the need for examiners to interpret the Airman Certification Standards (ACS), a reader who asked to remain anonymous pointed out that in my example of short field takeoff, while stall speeds in some sources do not specify whether the speed is knots indicated (KIAS) or calibrated (KCAS), in others the POH is more explicit. This changes—only slightly—my comments to read:

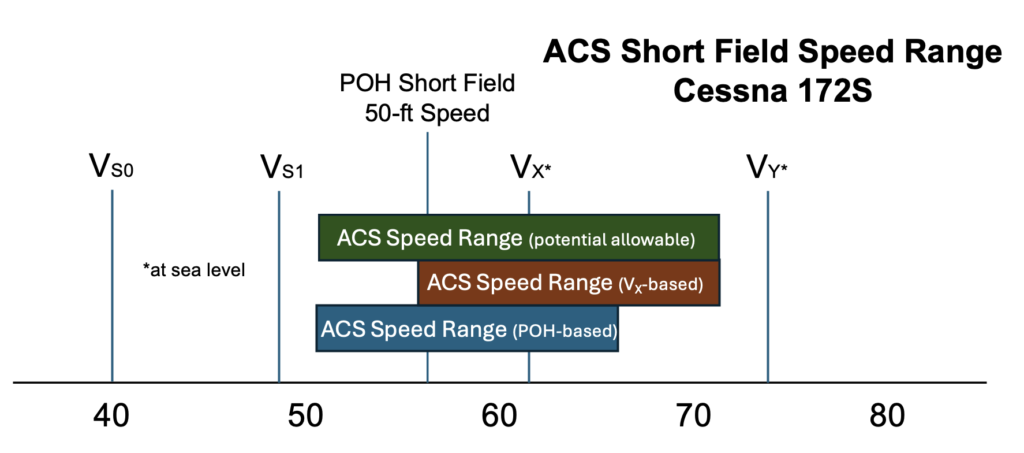

VS1 (stall speed, flaps up) in the C172S is 48 KIAS. VS0, stall speed at full flaps, is 40 knots. Cessna recommends 10° of flaps for a short field takeoff, and the decrease in stall speed is probably not along a straight-line from zero to full flaps. At 10° flaps stall speed is likely somewhere around 46 knots…meaning the acceptable range of ACS short field takeoff speeds may be within five knots of stall speed in the short field takeoff configuration…or even closer.

It doesn’t change my conclusions at all, being:

The stall warning horn is typically set to activate at five to seven knots above stall speed (or more correctly, the equivalent angle of attack margin). Is an examiner really going to pass an applicant who makes a short field takeoff with the stall warning shrieking continuously?

…and most importantly:

If you base short field takeoff speed on VX, 62 knots, the ACS-allowable speed range is 57 to 72 knots. If you follow the manufacturer’s guidance, the range is 51 to 66 knots. The ACS tells us that anywhere in a 21-knot range of 51 to 72 knots, from stall speed to just below VY, should be evaluated as a successful Short Field Takeoff maneuver. Would an examiner accept that?

To clean things up, here’s a revision of the graphic I made for last week’s report:

Our anonymous reader continues:

I tried to relate the KIAS and KCAS to the short field over 50 foot obstacle situation using the stall speed and calibration tables. There are several caveats presented as well as the inaccuracy of interpolation here, plus my somewhat limited knowledge. Nevertheless, here’s some of what I see:

The stall speed tables on Section 5-12 [of the C172S POH] say KIAS values are approximate. The airspeed calibration tables on Section 5-9 give the condition for “Power required for level flight or maximum power descent.” I wonder what the table would look like in a maximum power climb through 56 KIAS and 10 degrees flaps over the 50′ obstacle. Regardless, the difference between KIAS and KCAS is significant at lower airspeeds as seen in the stall speed tables (the “condition” being power off) but becomes less and approaching relatively equal at speed above the mid-60s to 70+ depending on flap setting.

My original point in my prior email was that the numbers you stated for KIAS from the POH were actually KCAS. The corresponding KIAS numbers are significantly lower. How all this correlates to the +10/-5 knots from the ACS has my brain smoking so I won’t even try. I have also seen some articles from respected instructors discussing speeds such as Vref from a POH such as this 172S, where they compute 1.3 Vso from the KIAS stall speed rather than from KCAS. That would give 52 knots KIAS, something like a 1.1 Vso or a little less. Truly a dangerous situation for the low-time pilot using this instead of using the 60-70 KIAS normal landing speeds from the POH.

What is the 1.3 Vso KIAS calculated off of KCAS? Depends whether one uses 48 KCAS from the stall speed table or 50 KCAS from the calibration table. Anyway, I think it’s somewhere in the 59-62 knot range. Whew!

Many years ago as a student pilot, I read about all this in Sparky Imeson’s Mountain Flying and spent hours trying to understand it. I even called [Spark] and he was gracious enough to walk me through it until I finally got it. I’m still a relatively low-time pilot and don’t consider myself any kind of an authority so if you were going to post any of this, please have me as anonymous. Look forward to hearing you present at Oshkosh.

Thank you, anonymous reader. Very heady. Read on for another reader’s observations.

Reader Steven Vook adds:

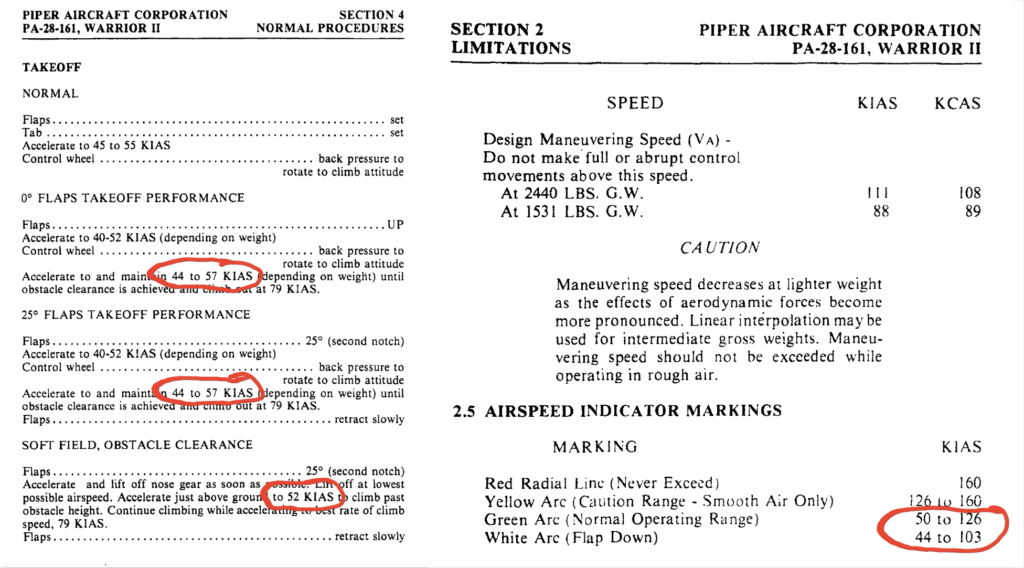

Your discussion on Vx vs ACS brings to mind the Piper Warrior (PA-28-161) and its confusing POH (see screenshots) with regard to obstacle clearance. I never have been able to get this one straight in my head. One would think that Vx would be the speed to use for obstacle clearance. They even go as far as to properly define Vx.

However, the amplified procedures for obstacle clearance takeoffs instruct the pilot to use an airspeed significantly slower than Vx. Having several hundred hours of instruction given in a [PA28-]161, I can promise you that following the POH procedure does, in fact, result in the stall warning horn blaring the entire time.

With 0 flaps, the pilot is supposed to maintain 44 to 57 knots (depending on weight) until obstacle clearance. The Green Arc bottoms out at 50 knots.

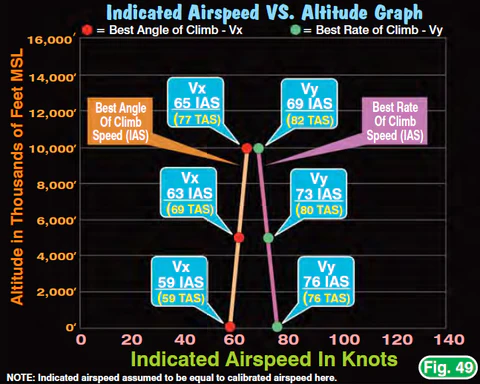

Master aviation educator (and FLYING LESSONS reader) Rod Machado describes the changes in VX and VY with altitude, relating the changes to changes in true airspeed. Bold Method also has a detailed explanation of why VX and VY change with altitude as a result of changes in parasitic and induced drag in different air densities. They’re both saying the same thing in different ways.

Vx and Vy vs. altitude (Rodmachado.com)

In his classic (at least in Beech circles) Flying the Beech Bonanza author John Eckalbar—using data he developed flight-testing his A36 Bonanza—postulates that the published values of VX and VY, at least in his airplane, appear to be valid at about 5000 feet. At altitudes below 5000 feet VX is slower than “book” and VY is faster. Maybe that’s right, and the airspeed for best angle of climb near sea level is several knots below the POH VX. That might explain why the amplified Short Field technique in the PA28-161 calls for climbing “significantly slower” than VX, and why while the C172S Short Field target speed is 56 KIAS the published VX is 62 knots “at sea level”…but is it really?

All this reinforces a substantial shortcoming in the Airman Certification Standards (ACS) that inspired this multi-edition discussion: to what extent does a pilot examiner have to define the criteria for success on a pilot certificate or rating Flight Test, and might an applicant for that certificate or rating be trained and prepared differently that what the examiner expects or requires while still being within the parameters of the ACS.

I find the topic baffling and fascinating. Perhaps regulators and the flight instructor professional associations (FLYING LESSONSsponsor NAFI, and SAFE) can work together to resolve the confusion. More importantly., we pilots need to know what reallyprovides maximum obstacle clearance performance before comes the time we actually need to use the technique.

More to say? Let us learn from you, at [email protected].

AOPA Presentation

Pilot Short Story: Emergency in IMC

About a year ago AOPA Air Safety Institute (ASI) asked me to come to Frederick, Maryland, to record several interviews for its updated online [electronic] Flight Instructor Refresher Clinic (eFIRC). While there I was asked to relate an unusual or emergency situation I’ve faced in flight…and I described a partial power loss while in Instrument Meteorological Conditions (IMC). AOPA applied its production magic and this week has published the result. Watch my Pilot Short Story: Emergency in IMC, and the LESSONS I learned from the experience, courtesy of AOPA ASI.

Share safer skies. Forward FLYING LESSONS to a friend

Please help cover the ongoing costs of providing FLYING LESSONS through this secure PayPal donations link. Or send a check made out to Mastery Flight Training, Inc. at 247 Tiffany Street, Rose Hill, Kansas USA 67133. Thank you, generous supporters.

Thank you to our regular monthly financial contributors:

Steven Bernstein, Montclair, NJ. Robert Carhart, Jr., Odentown, MD. Randy Carmichael, Kissimmee, FL. Greg Cohen, Gaithersburg, MD. John Collins, Martinsburg, WV. Paul Damiano, Port Orange, FL. Dan Drew. Rob Finfrock, Rio Rancho, NM. Norman Gallagher. Bill Griffith, Indianapolis, IN. Steven Hefner, Corinth, MS; Ellen Herr, Ft Myers, FL. Erik Hoel, Redlands, CA. Ron Horton. Robert Hoffman, Sanders, KY. David Karalunas, Anchorage, AK. Steve Kelly, Appleton, WI. Karl Kleiderer. Greg Long, Johnston, IA. Rick Lugash, Los Angeles, CA. Richard McCraw, Hinesburg, VT. David Ovad, Resiertown, MD. Steven Oxholm, Portsmouth, NH. Brian Schiff, Keller, TX. Paul Sergeant, Allen, TX. Ed Stack, Prospect Heights, IL; Paul Uhlig, Wichita, KS. Richard Whitney, Warrenton, VA. Jim Preston, Alexandria, VA. Johannes Ascherl, Munich, Germany. Bruce Dickerson, Asheville, NC. Edmund Braly, Norman, OK. Steven Hefner. Bruce Douglass, Conway, MA. Lorne Sheren, New Vernon, NJ

And thanks to these donors in 2024:

Jim Lara, Joseph Stadelmann, Dixon Smith, Barry Warner, Wayne Mudge, Joseph Vandenbosch, Ian Campbell, Jay Apt, John Kimmons, Derek Rowan, Michael Maya Charles, Ron Horton, Lauren McGavran, Gerald Magnoni, Amy Haig, Rod Partlo, Brent Chidsey, Mard Sasaki-Scanlon, SABRIS Aviation (Dave Dewhirst), Edmund Braly, Joseph Orlando, Charles Lloyd, Michael Morrow, Abigail Dang, Thomas Jaszewski Danny Kao, Gary Garavaglia, Brian Larky, Glenn Yeldezian, David Yost, Charles Waldrop, Robert Lough. Gilbert Buettner. Panatech (Henry Fiorientini). Dale Bleakney.

Pursue Mastery of Flight

Thomas P. Turner, M.S. Aviation Safety

Flight Instructor Hall of Fame Inductee

2021 Jack Eggspuehler Service Award winner

2010 National FAA Safety Team Representative of the Year

2008 FAA Central Region CFI of the Year

FLYING LESSONS is ©2024 Mastery Flight Training, Inc. For more information see www.thomaspturner.com. For reprint permission or other questions contact [email protected].