Topics this week include: > Fueling discussion > Creating scenarios > We’ve still got to do better

FLYING LESSONS uses recent mishap reports to consider what might have contributed to accidents, so you can make better decisions if you face similar circumstances. In most cases design characteristics of a specific airplane have little direct bearing on the possible causes of aircraft accidents—but knowing how your airplane’s systems respond can make the difference in your success as the scenario unfolds. So apply these FLYING LESSONS to the specific airplane you fly. Verify all technical information before applying it to your aircraft or operation, with manufacturers’ data and recommendations taking precedence. You are pilot in command and are ultimately responsible for the decisions you make.

FLYING LESSONS is an independent product of MASTERY FLIGHT TRAINING, INC.

Pursue Mastery of Flight™

This week’s LESSONS

Our most recent FLYING LESSONS report “fueled” reader discussion. So, let’s go straight to the Debrief.

Questions? Comments? Supportable opinions? Let us know at [email protected].

Debrief

Readers write about previous LESSONS

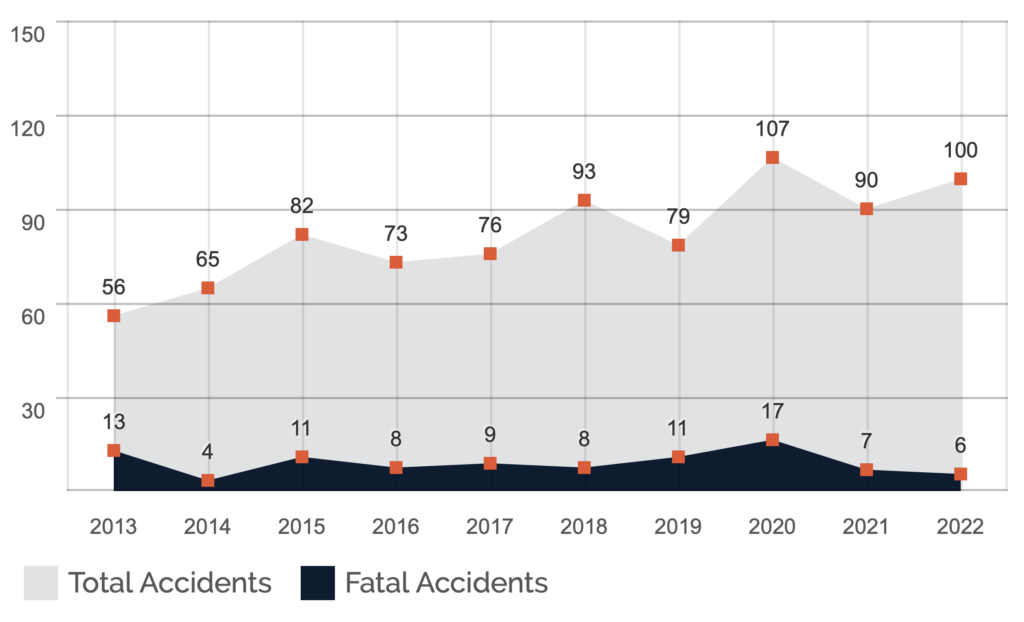

Reader and FLYING LESSONS supporter Mark Sletten writes about our December 19 LESSONS on fuel starvation and exhaustion accidents, the number of which AOPA Air Safety Foundation’s 2024 Richard G. McSpadden Report tells us has nearly doubled over the past decade:

It’s overwhelmingly sad and infuriating to think we are still dealing with this phenomenon despite all the emphasis from the FAA, NTSB, and CFIs. I conduct most of my primary flight training in C172s. I teach my students to dip the tanks prior to each flight, then compute maximum flight time on the spot based on 8 GPH fuel burn plus three gallons for engine start, takeoff, and climb. It takes all of 10 seconds, and maybe a single calorie of brain energy. During the flight I teach them to scan all engine instruments at each VFR checkpoint, including the fuel quantity indicators. The gauges may not be accurate enough to compute time remaining to fuel exhaustion, but they are accurate enough to show whether the indication makes sense given the amount you should have burned. A discrepancy requires a precautionary landing.

The Legacy I fly has advanced avionics, making fuel management easy and dead-on accurate. To start, I’ve developed ForeFlight performance profiles at several different altitudes which I’ve confirmed to be accurate within just a few percent. My personal minimum requires landing with at least one-hour of fuel remaining, and that’s the basis for computing starting fuel. The aircraft has both a fuel totalizer (indicates quantity in individual tanks as well as total quantity in both tanks), and a fuel flow indicator which displays flow rate, fuel remaining, and time to fuel exhaustion. The fuel/time remaining functions are based on an accurate starting fuel, which I confirm by dipping the tanks during preflight. I also confirm the fuel totalizer indication and total entered in the fuel flow indicator match.

The plane also has an air data computer which displays winds. After level-off I confirm winds are as forecast, set cruise power, check quantity in both tanks, set a timer to switch tanks based on the current quantities and flow rate, then confirm the fuel totalizer and fuel remaining computed by the fuel flow indicator match.

I also ensure the indicated time remaining to fuel exhaustion exceeds the ForeFlight-computed estimated time enroute (ETE) by at least one hour. I do this every time I switch tanks. These procedures are among those I verbalize while doing. Additionally, these are among the critical procedures I’ve taken the time to teach my wife, who is my most frequent flying companion on long cross-country flights. Having a second set of eyes on critical systems and flight procedures is one of the things that makes the pros so much safer than general aviation, and I take every opportunity to emulate them.

Noncommercial fixed wing fuel-related accidents 2013-2022 (2024 McSpadden Report)

Perhaps pilots neglect such procedures because they think them onerous, or that they take too much away from the enjoyment of flying. The truth is each of the above-described duties related to fuel management requires just a few seconds. For a typical three-hour flight I estimate maybe two total minutes spent scanning gauges, entering/confirming numbers, setting timers, and switching tanks. That’s just 120 seconds out of the 10,800 comprising a 3-hour flight. In my opinion, those relatively few seconds take nothing away from the enjoyment, but even if they did it’s a cheap price to pay to avoid a fuel exhaustion event.

I’ve not documented so well my inflight fuel status monitoring and system management technique (I need to rectify that), but it’s very similar to yours. I do frequent status checks to include fuel remaining upon landing, expressed in time as well as gallons. I add a scan behind the fuel filler caps and along the wing’s trailing edge to look for any sign of fuel siphoning through the caps or vent system, knowing that any fuel lost that way would not be included in the fuel totalizer’s calculations (and in the models of airplane I most commonly fly could create a falsely high indication on that wing’s fuel quantity indicator).

Unless you’re flying the stone-simple fuel systems with an ON position for fuel and not requiring manually switching tanks in flight (lower-end Cessna singles, later Beech Barons, etc.), the larger issue is to not only to manage how much fuel you burn, but also where you’re burning it from. Some fuel systems get very complex. Some have fuel return that does not go into the tank in use, draining the tank faster than the indicated fuel flow and totalizers suggest. Every “auxiliary” fuel tank I’ve ever seen or read about is prohibited for use during takeoff and landing, and additionally placarded for use in level flight only. It’s no wonder that fuel starvation accidents (fuel is on board but not getting to the engine) are more common in the accident record than fuel exhaustion events (running completely out of fuel).

Another inflight management technique I have written about many times, and which agrees with yours, is to crosscheck allavailable fuel quantity indicating systems and manual monitoring techniques. If any single status indicator does not agree with the others investigate it immediately; if you can’t positively determine the reason (with real data and knowledge, not just hope) then land as soon as practical and add or confirm fuel to resume with a known fuel level. For example, if one of your fuel quantity indicators shows fuel noticeably lower than you’d expect at that point in your flight don’t brush it off as a gauge accuracy issue. Heed it as a warning that fuel may be going overboard instead of through the engine(s).

As far confirming fuel quantity before takeoff, I’ve written about that many times also. Check every possible fuel level indication, including (but not limited to):

- Visual fuel level check, if there’s sufficient fuel in the tanks to see through the filler ports. Airplanes with significant wing dihedral may not have any fuel visible in the tank if the level is below ½ to ¾ full and cannot be “dipped” below that level either. That said, I diligently check fuel level with a calibrated dipstick in airplanes on which that is possible.

- Filler tabs and exterior wing-mounted fuel gauges. Some airplanes with wing dihedral have “sight gauges” in the wings to help assess less-than-full fuel levels. Some types have a tab or other “fixed internal dipstick” inside the fuel filler port. Check them.

- Fuel quantity indicators. The oft-maligned cockpit fuel gauges are actually the best “sanity check” against technological solutions that don’t register fuel leaks and can tell you how much fuel (they think) is on board but not where it is located. If a fuel gauge reads lower than expected, believe it. Conversely, if a gauge reads higher than expected, suspect it and other indicators may be wrong.

- Fuel totalizers. Within the previously stated limitations and “garbage in, garbage out” human input error, I’m a huge fan of fuel totalizers for accuracy. Check fuel added to fill the tanks against what the totalizer says it should take to see how accurate your totalizer may be. I check totalizer vs. fuel added every time I top off the tanks as a way of verifying the totalizer’s accuracy.

- Fueling records, including what you personally added or observed being put in the airplane, and fuel receipts (realizing that FBO fuel receipts may be the least accurate fuel quantity information).

Use everything you’ve got to confirm fuel level. Any discrepancy between any of the information sources must be investigated and repaired if necessary, and fuel quantity positively determined or added, before you board for flight…and while aloft. Thank you, Mark.

Frequent Debriefer and twin Cessna specialist instructor Dave Dewhirst adds:

Great article on fuel exhaustion. One additional area of discussion is fuel management. For example, the Cessna 340/414/421(A&B) models can have as many as six tanks and ten pumps. What could possibly go wrong? The NTSB files show one-third of the fuel related accidents in the C340 have fuel remaining somewhere in the aircraft [i.e., fuel starvation – tt], or the pilot reported the FBO did not add fuel to the correct tanks.

Another issue is a fuel system that has a strange method of operation. All of those same Cessna aircraft left the factory with a strange method of boost pump operation. In those systems, the boost pumps did not turn ON when the pump switches were placed in the ONposition. Activation of the boost pumps occurred when a sensor showed fuel pressure dropped, indicating the failure of an engine driven fuel pump. Those pumps were activated by a latching relay. When fuel pressure dropped the relay latched in the closed position providing fuel to the engine.

Great idea except when the pilot ran one tank dry, causing the loss of fuel pressure and causing the relay to latch closed. In a TCM [Continental] engine, if both the engine driven pump and the aux pump are both operating, the excess fuel will prevent the engine from operating. The pilot has restored fuel flow by switching tanks but the engine will not restart. The only fix is to shut off the airframe master switch (uh, what?). That will release the latching aux pump switch. Then, turn the master switch back ON. The engine can then be restarted.

When checking out in an unfamiliar airplane, be sure to understand all the ways to operate the [fuel] system. Most all of these airplanes have been modified and a placard placed in the airplane that explains the details. Always read all the placards.

We [Dave’s SABRIS Aviation instructors – tt] teach these procedures to check the fuel system before takeoff:

- Check each tank for the correct fuel needed and check the fuel receipt to be sure the amount added makes sense.

- Turn on the master switch and be sure all the electric pumps operate.

- Burn from or transfer fuel from all tanks that are expected to be used during the flight, just to be sure all the tanks contain fuel and actually work. One procedure is to start and taxi on one set of tanks and switch to another set for run-up. Just be sure to be on the correct tanks for takeoff.

- Burn some fuel from all the tanks within the first hour of flight just to be sure they all work. That leaves fuel available to find an alternate airport.

It’s no surprise (to me, anyway), that teaching the airplane’s fuel system and its indications and operations in normal, abnormal and emergency conditions is consistently the longest (if not the longest) segment of systems instruction in formal transition training programs. Even among similar airplanes and engines fuel system operation differs.

From my world, for example, running an auxiliary fuel pump ON or HIGH as appropriate in Beech Bonanzas and most Barons carries a Pilot’s Operating Handbook warning and in some models an airframe limitation against use in flight when the engine-driven pump is operating normally because the additive fuel pressure will decrease power output and under some conditions will flood the engine to failure. Yet, in turbocharged and pressurized Barons the fuel injection system is completely different and the POH calls for running the pumps on HIGH for all takeoffs and landings. Aux pump operation does not affect fuel flow to the engine in normal operation in those unique types.

So it really is a matter of following the checklists of the POH for the airplane you’re currently flying, and for seeking out type-specific knowledge and instruction for transition and recurrent training. Thanks as always, Dave.

Reader, Flight Instructor Hall of Fame inductee and TWA chief pilot, check airman and Vice President of Safety and Engineering Wally Moran continues:

Thanks, Tom for all your great work. Here is yet another way to run out of gas.

I lost two friends last year. Both experienced pilots and flight instructors. They landed late Sunday afternoon to get low-cost fuel, only to find the self-serve system inoperative and no other fuel available. They crashed shortly after takeoff and both pilots and a passenger were killed. The NTSB has not yet issued a Probable Cause but no fuel was found at the crash site.

The allure of lower-cost fuel at self-service pumps is great, and understandable. But I’ve had at least four personal experiences with self-serve where the pump did not work. Usually it’s an issue with the credit card reader because it has lost its internet connection—something that an airport worker can’t fix (if there’s even anyone there to ask; many self-serve pumps are at unattended airports).

I tend to steer toward airports with full-service fuel and other facilities on cross-country flights for greater reliability, even if it costs a bit more. Even then I’ve landed only to find the fuel truck is broken or for some other reason I can’t get fuel. That’s why I like to land with 1.5 hours of fuel on board, giving me a small range of operation to another airport that has fuel (after a confirmation phone call) and still be within my one-hour minimum after hopping to that location. If you plan to refuel at a self-serve pump I suggest you do the same, and arrive at that airport with enough still on board to go somewhere else without violating legal and personal minimums. Thank you, Wally. I’m very sorry about your friends.

Here’s something that I think plays a major part in fuel management mishaps: Almost all flight training, especially cross-country flying, begins with an airplane full of fuel with a trip that can be completed without having to refuel along the way. The system turns out pilots who never learn how to refuel an airplane (or even request fuel), and who are never challenged to truly manage the fuel system to ensure success including experience making an unexpected diversion when the fuel plan doesn’t work out as expected.

Was your formal training any different? Or did you figure out fuel management later, maybe after scaring yourself as you inched toward a beckoning runway not knowing for certain you had the fuel to make it there?

Flight instructors: Are you intentionally creating scenarios where your student must decide to add fuel during a training flight? Are you creating real-world fuel management scenarios that result in a diversion and a precautionary landing for more gas in your dual instruction? Are you teaching your students how to ground and fuel an airplane with a self-serve pump, and how to order fuel and oversee fueling operations from full service FBOs? Do you teach emergency range extension by reducing power and/or aggressively leaning the engine? Are you drilling into them never to pass by an airport with fuel available if they have any doubt about their ability to make it to destination with reserves intact? These are all skills pilots may need when out on a solo cross country and will need immediately after they leave your tutelage. Who will teach them if not you?

As I wrote last time, we’ve got to do better. That’s a New Year’s resolution we can all live with.

More to say? Let us learn from you, at [email protected].

Share safer skies. Forward FLYING LESSONS to a friend.

Please help cover the ongoing costs of providing FLYING LESSONS through this secure PayPal donations link. Or send a check made out to Mastery Flight Training, Inc. at 247 Tiffany Street, Rose Hill, Kansas USA 67133. Thank you, generous supporters.

Thank you, all who responded to my annual “just one hour” request for help covering the costs of hosting and delivering FLYING LESSONS. And as always, thanks to all these supporters:

Thank you to our regular monthly financial contributors:

Steven Bernstein, Montclair, NJ. Robert Carhart, Jr., Odentown, MD. Greg Cohen, Gaithersburg, MD. John Collins, Martinsburg, WV. Dan Drew. Rob Finfrock, Rio Rancho, NM. Norman Gallagher. Bill Griffith, Indianapolis, IN. Steven Hefner, Corinth, MS; Ellen Herr, Ft Myers, FL. Erik Hoel, Redlands, CA. Ron Horton. David Karalunas, Anchorage, AK. Steve Kelly, Appleton, WI. Karl Kleiderer. Greg Long, Johnston, IA. Rick Lugash, Los Angeles, CA. Richard McCraw, Hinesburg, VT. David Ovad, Resiertown, MD. Steven Oxholm, Portsmouth, NH. Brian Schiff, Keller, TX. Paul Sergeant, Allen, TX. Paul Uhlig, Wichita, KS. Richard Whitney, Warrenton, VA. Jim Preston, Alexandria, VA. Johannes Ascherl, Munich, Germany. Bruce Dickerson, Asheville, NC. Edmund Braly, Norman, OK. Steven Hefner. Lorne Sheren, New Vernon, NJ. “The Proficient Pilot,” Keller, TX. Ed Stack, Prospect Heights, IL. Kynan Sturgiss, Hereford, TX. Bluegrass Rental Properties, LLC, London, KY.

NEW THIS WEEK: John Foster.

And thanks to these donors in 2024:

Jim Lara, Joseph Stadelmann, Dixon Smith, Barry Warner, Wayne Mudge, Joseph Vandenbosch, Ian Campbell, Jay Apt, John Kimmons, Derek Rowan, Michael Maya Charles, Ron Horton, Lauren McGavran, Gerald Magnoni, Amy Haig, Rod Partlo, Brent Chidsey, Mard Sasaki-Scanlon, SABRIS Aviation (Dave Dewhirst), Edmund Braly, Joseph Orlando, Charles Lloyd, Michael Morrow, Abigail Dang, Thomas Jaszewski Danny Kao, Gary Garavaglia, Brian Larky, Glenn Yeldezian, David Yost, Charles Waldrop, Robert Lough. Gilbert Buettner. Panatech (Henry Fiorientini). Dale Bleakney. Mark Kolesar. John Winter. Donald Bowles. David Peterson. Bill Abbatt. Bruce Jacobsen. Denny Southard, Wayne Cloburn, Ross Ditlove. “Bonanza User,” Tad Santino, Steven Scharff, Kim Caldwell, Tom Carr, Michael Smith. David Kenny. Lorne Sheren. Stu Spindel. Martin Sacks. Arthur Utay. John Whitehead. Brenda Hanson. Mark Sanz. Tim Schryer. Bill Farrell. Todd LeClair. Craig Simmons. Lawrence Peck. Howard Page. Jeffery Scherer. John Kinyon. Lawrence Copp. Joseph Stadelmann.

NEW THIS WEEK: Mark Richardson. Mark Sletten. David Hanson. Gary Palmer. Glenn Beavers. Bruce Jacobsen. Devin Sullivan. Wayne Colburn. Robert Weinstein. Robert Dunlap. Allen Leet. Peter Grass. Richard Benson.

Pursue Mastery of FlightTM

Thomas P. Turner, M.S. Aviation Safety

Flight Instructor Hall of Fame Inductee

2021 Jack Eggspuehler Service Award winner

2010 National FAA Safety Team Representative of the Year

2008 FAA Central Region CFI of the Year

FLYING LESSONS is ©2025 Mastery Flight Training, Inc. For more information see www.thomaspturner.com. For reprint permission or other questions contact [email protected].