Topics this week: > Stabilized go-around > Landing too fast > Fly the airplane you’re flying

Stabilized Go-Around

Reader/instructor Mark Sletten commented about last week’s LESSONS: “…we should be teaching students stabilized go-around criteria as well.”

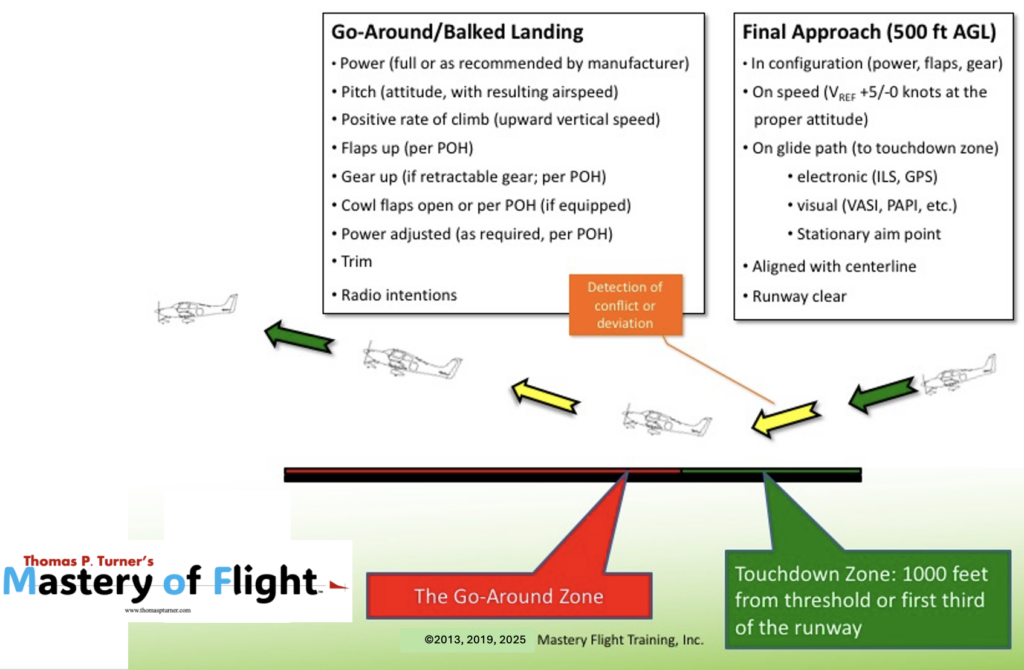

Going around is as natural a part of flying as landing or taking off…or it should be, if you occasionally practice the task. If you don’t meet the in configuration, on speed, on glidepath to the touchdown zone, in alignment with the runway centerline with zero sideways drift and the runway is clear criteria for continuing a landing, immediately initiate a go-around (sometimes called the balked landing procedure). Do not try to “salvage” an out-of-tolerance approach within 500 feet of the ground.

When “on the go,” satisfy these stabilized go-around criteria:

Power. Advance the power to full or as recommended by the airplane manufacturer. This includes leaning the mixture for best power at high density altitudes in most normally aspirated, piston-powered airplanes (some engines do this automatically). Most turbocharged powerplants should be at Full Rich mixture, and turbine condition levers should be in the takeoff position adjusted for conditions as necessary, or as otherwise described in that aircraft’s flight manual.

Pitch. Establish the proper pitch attitude. If you’re below an obstacle’s height start with the attitude that results in VX, or Best Angle of Climb speed. If your climbout path will be well above obstacles you can establish VY, or Best Rate of Climb speed, realizing that the airplane will cover more ground to reach a given altitude. In multiengine airplanes you should establish a shallow climb attitude and accelerate to VYSE, or “blue line” speed, unless you have to clear an obstacle, when VXME attitude is appropriate at the beginning of the go-around.

Positive rate. Use the Vertical Speed Indicator (VSI) to confirm the airplane is maintaining a positive rate of climb.

Flaps up as recommended by the Pilot’s Operating Handbook or Airplane Flying Manual (POH/AFM).

Gear up as applicable, as recommended by the POH/AFM.

Cowl flaps open, if equipped, as recommended by the POH/AFM.

Power adjusted, as necessary, if the POH/AFM mandates or recommends a power reduction for climb.

Trim the airplane for climb.

Radio your intentions to other airplanes and/or ATC as appropriate.

Beware the somatogravic effect, or the “false climb illusion.” As an aircraft accelerates, the sensory hairs in the pilot’s inner ear bend rearward under inertia. This is the same movement that occurs when an airplane pitches upward steeply. If the rate of acceleration is great, and the outside visibility is limited by darkness or obstructions to vision, the pilot may interpret the somatogravic effect as a steep climbout and instinctively push forward on the controls, reducing the climb or even putting the airplane into a descent. There are many instances when an airplane impacted obstacles far beyond the departure end of the runway during takeoff or go-around at night or in severely limited visibility, and the “false climb illusion” is suspected as a contributing factor.

Your defense against the somatogravic effect is to establish the proper attitude, through the combination of visual references backed up by the attitude indicator, and solely by reference to instruments on a dark-night departure or go-around, or when taking off or executing a balked landing in reduced visibility or instrument conditions.

Questions? Comments? Supportable opinions? Let us know at [email protected].

Debrief

Readers write about previous LESSONS

Reader Art Utay writes more about last week’s report:

I began reminiscing when I read about causes of hard landings. Your statement, “The pilot flies too fast and does not slow to touchdown speed before impacting the runway” brought back vivid memories observing the “Lufthansa Air Force” back in the ‘80s and ‘90s when I lived in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Lufthansa had a fleet of [Beech] Bonanzas they flew out of Goodyear Airport west of Phoenix. Goodyear was a towered airport (due to proximity to Glendale Airport and Luke Air Force Base) and I (and many friends) would routinely fly our 172s, 182s, Warriors, and other light singles over from the east side of town.

Pattern work was hazardous at Goodyear. All of us “light iron” types would fly appropriate speeds on downwind, base, and final with a flare at around 55-60 knots at touchdown. This procedure was unacceptable to the Lufthansa planes, which would barrel down final at upwards of 120 knots, often putting wheels on pavement at speeds in excess of 100 knots (I’m not exaggerating). Adding to the drama was a distinctly German accent screaming at you on final to get out of the way. Obviously, this led to some heated radio exchanges.

The FAA finally stepped in and held a public meeting with Lufthansa, various pilot groups, pilots, and the local FSDO. Lufthansa explained they were conducting ab initio training for their pilots, needed to acclimate them to jet speeds, and we slow pokes were advised to stay clear. They also expressed a view that since they were providing significant economic benefit to the community via training, fuel sales, lodging, food, etc., they should be given priority with regard to flight operations.

The outcome was that Lufthansa maintained their maintenance and hangar facilities at Goodyear, but built a runway out in the desert southwest of town. Every morning the “LAF” would depart Goodyear and in the evening return, leaving us “amateurs” alone.

Ah, good times.

This brings to mind a phrase I’ve used many times: Fly the airplane you’re flying, not the airplane you want it to be.Touchdown speed in a late-model F33A Bonanza (the model used by the “LAF”) should be in the low 50s-knot range (at or slightly above stall speed as adjusted for weight), following a roundout flare beginning from a 50-foot above runway threshold speed in the upper 60s-knot range, 1.3 times the full-flaps stall speed (again adjusted for weight). Landing substantially faster, as much as 100 knots crossing the runway threshold, would cause significant float in the flare; forcing the airplane onto the runway much faster than “book” risks Loss of Directional Control on the Runway (LODC-R) and landing gear failure, or perhaps landing gear damage that causes failure later even in a “normal” landing. Thank you, Art.

Reader and Expanded Envelope Exercises instructor Ed Wischmeyer adds:

A couple more thoughts on stable approach:

The concept of stable approach was clumsily promulgated for airliners by the Flight Safety Foundation 25 years ago, not based on complete data but possibly more to conform their operational preferences. (See my article “The Myth of the Unstable Approach”).

With complete data finally examined, a 200 foot callout has appeared in many airline operations in recent years. For light planes the question is not whether the approach should be stable, but for how long. For most single engine planes in less than extreme conditions and with pilots of only moderate skill, a 200 foot go-around decision may be nicely conservative . BUT…

Crosswinds, gusts, thermals, and down drafts can make any light airplane approach become unstable, according to many definitions. However, it is pilot skill and judgment that (should) arbitrate between safety and flight completion in any given situation In other words, determining when an approach is “too” unstable. Risk management… And there have been airliner accidents that were stable at 500 feet but came to grief in raucous air below 300 feet.

Diversions to other airports are pre-planned for airliners, rarely for light planes. In other words, if the approach is “unstable,” then what? (Discussion of weather forecasts, fuel at alternate, etc. omitted).

There is another but seemingly rare contributor to poor landings, and that is shallow approaches. At runways which have a sloped underrun on the approach end, I speculate that the short of the runway slope can create an optical illusion of being on glidepath when the airplane is actually too low, analogous to the well-known glidepath visual illusions that may come from runway edge lights at night on sloped runways. I have recreated this in flight test but have not sought accident data.

Such a too-shallow approach can also give the visual illusion of excessive speed, leading to a too-slow approach. This is analogous to density altitude giving a visual illusion of adequate speed when the airspeed is in fact too low..

Lastly, there are numerous examples of landing runway excursions (to the side, not overruns) being preceded by poor longitudinal control, both on approach and in flare. One of my datasets indicated this rate to be 46%.

True, the decision to go around begins at 500 feet above ground level, if not higher, but that’s only the beginning. Pilots must continue to evaluate the quality of the approach all the way to touchdown and the possibility of a go-around exists even in the first moments after landing if going around is safer than the alternative of a runway excursion or collision with an object on the runway. Thanks, Ed.

Reader/instructor Mark Sletten concludes this week where we began:

Another excellent FLYING LESSONS, Tom. I believe one of the most difficult things to teach a pre-solo student is how to recognize an unstable approach. In addition, and given your recent LESSONS on the importance of aircraft control during go-arounds, I think we should be teaching students stabilized go-around criteria as well. It doesn’t do any good if a pilot recognizes they are unstabilized on approach only to stall the aircraft while attempting a go-around. To me, these go hand-in-hand.

Briefing the criteria pre-solo students must monitor throughout approach and go-around on the ground is not enough; most students at this stage in training are too busy flying the plane to evaluate their progress. I’ve found it ineffective to harangue a student with stabilized approach/go-around criteria while they are desperately trying to learn the intricate psychomotor skills of controlling the plane during these phases of flight, often leading to frustration for both student and instructor. Instead, I use student-monitored demonstration. All of this is pre-briefed on the ground, so the student knows what to expect. I have the student fly the pattern until positioned on final, then I take control and fly the final approach. The student is to observe my progress and notify me when I exceed any pre-briefed stabilized approach criteria. I base my decision on which limit(s) to exceed on where the student put me on final. For example, if we roll out too high on final then speed and descent rate on final will be high; if we are off extended centerline then I exceed roll limits, etc. I brief students to identify the criteria exceeded, call a go-around, then talk me through the go-around procedure. They must monitor airspeed, pitch/bank angles, descent rate, power setting, and configuration down final and during the go-around. I emphasize that self-evaluating stabilized approach criteria and performing safe go-arounds are two of the critical skills I need to see before I can endorse them for solo flight.

Thanks again, Tom, for your excellent newsletter. Keep up the good work!

And thank you for your excellent additions, Mark.

More to say? Let us learn from you, at [email protected]

Share safer skies. Forward FLYING LESSONS to a friend.

Please help cover the ongoing costs of providing FLYING LESSONS through this secure PayPal donations link. Or send a check made out to Mastery Flight Training, Inc. at 247 Tiffany Street, Rose Hill, Kansas USA 67133. Thank you, generous supporters.

Thank you to our regular monthly financial contributors:

Steven Bernstein, Montclair, NJ. Robert Carhart, Jr., Odentown, MD. Greg Cohen, Gaithersburg, MD. John Collins, Martinsburg, WV. Dan Drew. Rob Finfrock, Rio Rancho, NM. Norman Gallagher. Bill Griffith, Indianapolis, IN. Steven Hefner, Corinth, MS; Ellen Herr, Ft Myers, FL. Erik Hoel, Redlands, CA. Ron Horton. David Karalunas, Anchorage, AK. Steve Kelly, Appleton, WI. Karl Kleiderer. Greg Long, Johnston, IA. Rick Lugash, Los Angeles, CA. Richard McCraw, Hinesburg, VT. David Ovad, Resiertown, MD. Steven Oxholm, Portsmouth, NH. Brian Schiff, Keller, TX. Paul Sergeant, Allen, TX. Paul Uhlig, Wichita, KS. Richard Whitney, Warrenton, VA. Jim Preston, Alexandria, VA. Johannes Ascherl, Munich, Germany. Bruce Dickerson, Asheville, NC. Edmund Braly, Norman, OK. Steven Hefner. Lorne Sheren, New Vernon, NJ. “The Proficient Pilot,” Keller, TX. Ed Stack, Prospect Heights, IL. Kynan Sturgiss, Hereford, TX. Bluegrass Rental Properties, LLC, London, KY. John Foster. Joseph Victor, Bellevue, WA. Chris Palmer, Irvine, CA.

Thanks also to these donors in 2025:

John Teipen. N. Wendell Todd. David Peterson. Jay Apt. SABRIS Aviation/Dave Dewhirst. Gilbert Buettner. David Larsen, Peter Baron, Glen Yeldezian, Charles Waldrop, Ian O’Connell, Mark Sletten, Lucius Fleuchaus. Thomas Jaszewski. Lauren McGavran. Bruce Jacobsen, Leroy Atkins, Coyle Schwab

NEW THIS WEEK: Michael Morrow, Lew Gage

Pursue Mastery of Flight(TM)

Thomas P. Turner, M.S. Aviation Safety

Flight Instructor Hall of Fame Inductee

2021 Jack Eggspuehler Service Award winner

2010 National FAA Safety Team Representative of the Year

2008 FAA Central Region CFI of the YearFLYING LESSONS is ©2025 Mastery Flight Training, Inc. For more information see www.thomaspturner.com. For reprint permission or other questions contact [email protected].