FLYING LESSONS uses recent mishap reports to consider what might have contributed to accidents, so you can make better decisions if you face similar circumstances. In most cases design characteristics of a specific airplane have little direct bearing on the possible causes of aircraft accidents—but knowing how your airplane’s systems respond can make the difference in your success as the scenario unfolds. So apply these FLYING LESSONS to the specific airplane you fly. Verify all technical information before applying it to your aircraft or operation, with manufacturers’ data and recommendations taking precedence. You are pilot in command and are ultimately responsible for the decisions you make.

FLYING LESSONS is an independent product of MASTERY FLIGHT TRAINING, INC.

Pursue Mastery of Flight™

This week’s LESSONS:

Just the Beginning

A Cessna 210L commenced a take‑off from runway 10 at Groote Eylandt Airport, Northern Territory [Australia] with a pilot and five passengers on board.

The Australian Transport Safety Bureau reports: Shortly after becoming airborne, at an altitude of 100 feet, the pilot reported that the engine began to surge, accompanied by fuel flow fluctuations. During the attempted turn back and landing, the aircraft passed diagonally over the runway then touched down in a clear grassed area outside the airport boundary. The aircraft continued along the ground for about 120 meters and hit an embankment. The aircraft flipped and came to rest inverted on a service road.

Three passengers received serious injuries while the pilot and two passengers sustained minor injuries. The aircraft was substantially damaged.

ATSB concludes: [The] accident…followed a partial power loss due to the engine mixture probably not being set to full rich highlights the importance of pilots familiarising themselves with aircraft systems and the operational environment, and a well-structured take-off safety brief.

It’s true that increased knowledge of “aircraft systems and the operational environment, and a well-structured take-off safety brief” might have led to a better outcome. But what exactly does that mean? How can a pilot translate this conclusion into avoiding similar accidents, or at least reducing their adverse effects?

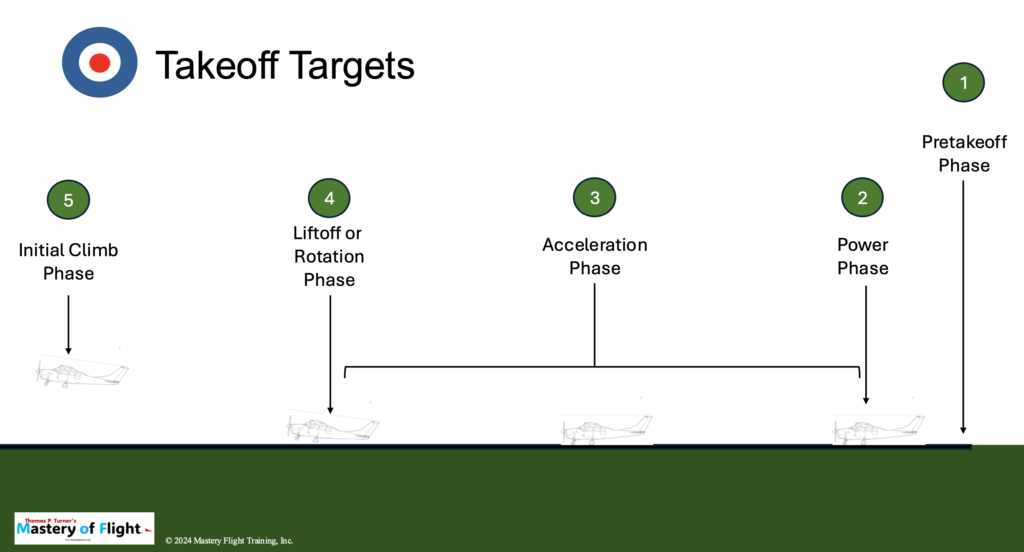

Takeoff Targets

You can divide a takeoff into five phases, and for eeach phase set goals, or targets. Only then can you correctly determine if your takeoff is going to be successful, and if not, abort while there’s still time. The phases of a takeoff are:

- The pre-takeoff phase

- The power phase

- The acceleration phase

- The liftoff or rotation phase

- The initial climb phase

PRE-TAKEOFF: A successful takeoff begins even before you board. This is when you evaluate the airplane, pilot technique and environmental factors that affect takeoff performance. How much distance will your takeoff require, and how long is the available runway? Are obstacles or rising terrain on your departure path? What’s the airplane’s weight? How strong is the wind? How will you determine the engine(s) is/are developing maximum available power…and what does that maximum look like under current conditions? What is the proper technique for this particular takeoff? Should you use flaps, or not? Answer these questions, and those from the remaining phases of a takeoff, in the pre-takeoff phase.

POWER: Is your airplane producing maximum available power? You won’t know unless you’ve established some power targets. In a fixed-pitch propeller airplane you should know the static RPM—the tachometer indication at full throttle and with no forward motion—and compare that to what you see at power-up. You’ll need to know the expected RPM as the prop spins up during the takeoff roll also.

If your airplane has a manifold pressure gauge know what you’ll see at full throttle. Most engines lose about one inch of air pressure around a fully-open throttle…so a wide-open engine at sea level should get around 29 inches of manifold pressure most days. Take that airplane to Denver, Colorado (elevation around 5300 feet) and it will get about 24 inches at full throttle—air pressure, and therefore manifold pressure for a normally aspirated engine, loses about one inch of pressure for every 1000 feetabove sea level.

What’s the optimum takeoff mixture? That will depend on altitude also. Check your airplane’s Pilot’s Operating Handbook(POH) or Airplane Flying Handbook (AFM) for specific guidance, but in general fixed-pitch propeller engines need to be leaned for maximum propeller speed at full throttle. Those with controllable pitch propellers should be leaned per POH fuel flow tables (often placarded on the airplane’s fuel flow gauge) or for a target Exhaust Gas Temperature (EGT) setting. Turbocharged engines have their own targets. Regardless, know what indication you’re leaning for, and lean the mixture for that setting before beginning your takeoff roll. Ask yourself: what do you need to do with the mixture control to reach your power target?

ACCELERATION: Does it “feel” right? Do you get your expected propeller RPM on the takeoff roll? A better measure of acceleration is to visualize, beforehand, the point along the runway at which you expect to reach rotation speed. A rule of thumb is that you should be at 70% of liftoff speed when you pass 50% of the computed ground roll distance.

Some pilots use other methods that may be as good. The trick is to find one that works and then use it consistently.

LIFTOFF or ROTATION: Reaching your rotation speed target at the predetermined distance down the runway, raise the airplane’s nose to the necessary attitude. Whether visually or on instruments, there is one best attitude that provides optimum climb performance. Reach that attitude (VY or, if obstacles are a factor, a Vx attitude), and the airplane will climb smartly. A few degrees more nose up and induced drag may seriously degrade climb performance. A few degrees more down and climb rate may also be significantly eroded.

INITIAL CLIMB: If you’ve used flaps for the takeoff, leave them set until you’ve confirmed a positive rate of climb and have cleared all obstacles. Don’t pull up retractable landing gear too soon, either; many retractable gear designs suffer from a significant, climb-robbing drag increase while in transit. Have a pre-takeoff idea of your expected climb attitude and vertical speed. Compare “real” to “expected” to decide if your takeoff is going as planned.

The idea of this five-phase series of Takeoff Targets is to know beforehand what to expect in each phase as it unfolds, and to immediately abort the takeoff if you detect you are not attaining one of your preplanned targets. Don’t try to figure out whywhile still taking off; immediately reject the takeoff and troubleshoot the problem after you’ve taxied clear of the runway, conferring with a mechanic (“engineer,” for this Aussie example) if needed.

Many larger engines’ fuel pumps are biased to very high flow rates to assist with engine cooling at high power settings. Often a side effect is very rich fuel flows at low power, and the need to aggressively lean the mixture for engine smoothness on the ground and to avoid carbon buildup on spark plugs that can reduce takeoff power. It’s common to “ground-lean” big-engine piston airplanes; this means you have to remember to set the mixture control correctly soon before beginning your takeoff roll.

I suspect that, had the Cessna 210 accident occurred in the United States instead of Australia, that the NTSB’s Probable Cause report would have been more focused on “failure to use a checklist” before takeoff that led to forgetting to advance the mixture control…a worthwhile conclusion, but still one that requires more prediction and detection between engine start and transition to cruise climb.

Checklist omission is just the beginning of an accident chain that can be broken. Practice setting Takeoff Targets for every takeoff, and actively check actual performance against those targets during takeoff. Using this technique the pilot of the Cessna 210 most likely would not have progressed far enough along his takeoff roll to get into the air with a partial power loss, and we would not have had to attempt a return to the runway.

Questions? Comments? Supportable opinions? Let us know at [email protected].

Debrief

Readers write about past FLYING LESSONS:

Reader Stu Spindel writes about the August 8 LESSONS on takeoff technique and performance:

I suspect it is the rare pilot who adjusts takeoff liftoff airspeed for different weights. Most will use the airspeed for [Maximum] Gross Weight listed on their checklist. That is my observation after flying with many different pilots with virtually all flights at rather light weights.

Granted the difference might be two or three knots, but it could allow for one or two hundred feet. Also, the high density altitude should have signaled a mixture adjustment. Operations closer to the performance limits require greater precision.

I agree, Stu. Taking it further, in my experience many pilots don’t take off at a precise airspeed at all. They allow the airplane to lift off “when it’s ready to fly.” That results in a smooth takeoff, but it doesn’t result in optimal performance. Almost always that’s not important. But with a heavy load, on an extremely hot day that creates a high density altitude, it can be fatal.

Reader Dan Drew adds to the August 1 LESSONS:

Very good article about the MEL [Minimum Equipment List’ for commercial ops and the KOEL [Kinds of Operation and Equipment List] for non-commercial. We had “deferral stickers” [at a major commercial jet operation] that were authorized from maintenance and dispatch and the crew authorizing operations with items inop[erative]. These had been researched and “proven” to be an acceptable “risk” as long as a prescribed plan was followed. We used to joke that the fire hazard was the number of stickers.

We may not be fully aware of how the systems interact with each other and especially if a CB [circuit breaker] is required to be pulled.

The comments about insurance and legality is a good reminder.

Thank you, Drew. I think the jet operation you flew with was a Part 91K fractional ownership, which may or may not have been on an MEL. Regardless, the sticker system sounds like a good technique for an operation with a lot of aircraft and an even greater number of pilots.

Reader and extremely active weekend pilot John Majane continues the Debrief from the August 1 report:

The discussion here about landing gear and flaps is interesting. It does point out to people not using their checklists whether written or verbal. Part of pre-takeoff checklist is the flaps for operation and position. How the Baron pilot missed it? Checklist. The landing gear and approach flaps is also interesting. I do not have approach flaps in my [1955] F35 [Bonanza] but with all planes I have flown with retracts I use the same procedure. Opposite the numbers on downwind or an appropriate distance on final I do an initial GUMPSF Check. The F being for Flaps (Cowl and Wing). I then do another check shortly thereafter. On base or a mile out on final I do a third check and check for long final traffic if applicable. On short final I do a final three in the green and everything forward (propeller and mixture) to make sure the gear is down and I am set up for a go around. I know this sounds repetitive and over doing it but it is my routine and I do not deviate from it which I believe prevents accidents. I am strong advocate of checklist use. Doing the same thing every time, no deviations.

As I wrote in that edition, the ultimate solution: regardless of whatever else you do, confirm gear extension before crossing the runway threshold every time, and go around immediately if the gear is not confirmed to be down, without hesitation. Thank you, John.

Instructor Anthony Poundstone adds:

Your observation “extend the gear before landing” is right on point. I think I would not be too far off base to say that 100% of unintentional gear up landings could be prevented by that simple mantra!

A humorous anecdote: When I was working for the big OEM across the field from your previous office at KICT I went to a big type gathering for small jet owners in West Virginia. We brought I think 6 or 7 airplanes for static display. Hanging around on the ramp watching arrivals a Mustang flown by an experienced demo pilot was flaring to land when he cobbed the power, literally bounced off the runway, and went around. Uneventful second arrival.

He had several company employees aboard (some of whom were pilots). Over a beer later the obvious question was, “What was that?” He said, “I just had a horrible thought I hadn’t put the gear down.” My response was, “so why didn’t you put one of the sales guys in the left seat when you came back around?”. He said he wished he had thought of that!

This is something like what we quipped in U.S. Air Force Flight Screening in the mighty T-41A Mescalero: in the event of an engine fire in flight that doesn’t go out, slip so the flames go toward the instructor’s side of the airplane. Sometimes aviation safety is helped with a little humor. Thanks, Tony.

Reader Lorne Sheren comments on the August 15 LESSONS:

An additional comment about ops specs that you have made in the past is that there’s nothing stopping you from developing your own (unapproved except for your spouse) personal ops specs. Which can be modified. For example if you’re a bit rusty in your instrument skills maybe your minimum ceiling on any approach might be 500 or even 1000.’ Maybe you’re rusty on crosswinds- reduce your personal crosswind op spec from the published wind speed. Maybe you are flying with a new panel. Up the minimums until you are comfortable both with the display and how to program it. And pledge not to violate the specs you developed at 0 altitude, 0 airspeed and 1G. There’s no reason we can’t fly with the same assurances that our “professional” colleagues have. It just takes honesty and discipline to do what we know is right, not what is expedient.

Absolutely right. The regulations give us a minimum standard of safety. We can always demand more from ourselves. Thank you, Lorne.

Reader Joel Vandersluis takes us back to the July 11 FLYING LESSONS Weekly:

[I] appreciate your article about leaning and best climb. I fly a [Diamond] DA40 from an airport at 1000 AGL. Never had much training on leaning before takeoff. If I lean to target EGT at runup (2000 RPM) might I be too lean for takeoff at just under 2700? Any other recommendations? Appreciate your insights.

The Target EGT method works best when you line up in position for takeoff on the runway, advance throttle to full and then lean to the appropriate exhaust gas temperature. You can lean in the runup area at runup power to find peak EGT, then enrichen the mixture to about 75° to 100°F (around 25° to 40°C). The DA40 Pilot’s Operating Handbook recommends “approximately” 100°F (about 40°C) for maximum horsepower “at all altitudes,” that would include takeoff. Leave the mixture control in that position when you reduce throttle at the end of your runup; when you advance to full power for takeoff the mixture should be close to Target EGT, and you can enrichen (if below your target) or lean (if above target) as needed. Thanks, Joel.

Wrapping up this week’s Debrief, well-known, Ohio-based flight instructor Peg Ballou writes:

Dear Tom, I appreciate your weekly reminders to be safe out there and recently really been impressed by the instructor encouragement to not do touch and goes. I have never really used touch and goes in instruction because I want the time taxing back to cover what happened on the last trip.

Unfortunately, this week we had an example of a poor event on a go-around, in which a soloing student stall spun after “eight touch and goes.” When a student—especially a student on a first solo—is rushing to clean up and get ready to go. It’s way too easy to have something happen and procedures forgotten. I think this is the reason why we instructors don’t have a student solo the plane from start-up. At least we know it is up and running properly when we get out of the plane. I exhort the pilot that this is the “one and only time you let someone get out of the plane with that rotating meat cleaver going in the front.”

Additionally, I appreciate [the July 11) Master Lessons on the stall /pin that amazingly did NOT result in a fatality in Colorado. I plan to print that out and use it as a LESSON for my students with the video track.

Blessings on you for your work. Hope to see you at AirVenture.

I’m gratified to be a part of your work producing new pilots, Peg. And thanks for dropping by my remote office at Oshkosh. Once more, I recognized you waiting very patiently to say hello and am sorry I could not get away before you had to leave. Next year let’s set up a time and I’ll be sure to get away. Thanks again.

More to say? Let us learn from you, at [email protected]

Thank you to the National Association of Flight Instructors for renewing its annual sponsorship

Share safer skies. Forward FLYING LESSONS to a friend.

Please help cover the ongoing costs of providing FLYING LESSONS through this secure PayPal donations link. Or send a check made out to Mastery Flight Training, Inc. at 247 Tiffany Street, Rose Hill, Kansas USA 67133. Thank you, generous supporters.

Thank you to our regular monthly financial contributors:

Steven Bernstein, Montclair, NJ. Robert Carhart, Jr., Odentown, MD. Randy Carmichael, Kissimmee, FL. Greg Cohen, Gaithersburg, MD. John Collins, Martinsburg, WV. Paul Damiano, Port Orange, FL. Dan Drew. Rob Finfrock, Rio Rancho, NM. Norman Gallagher. Bill Griffith, Indianapolis, IN. Steven Hefner, Corinth, MS; Ellen Herr, Ft Myers, FL. Erik Hoel, Redlands, CA. Ron Horton. Robert Hoffman, Sanders, KY. David Karalunas, Anchorage, AK. Steve Kelly, Appleton, WI. Karl Kleiderer. Greg Long, Johnston, IA. Rick Lugash, Los Angeles, CA. Richard McCraw, Hinesburg, VT. David Ovad, Resiertown, MD. Steven Oxholm, Portsmouth, NH. Brian Schiff, Keller, TX. Paul Sergeant, Allen, TX. Ed Stack, Prospect Heights, IL; Paul Uhlig, Wichita, KS. Richard Whitney, Warrenton, VA. Jim Preston, Alexandria, VA. Johannes Ascherl, Munich, Germany. Bruce Dickerson, Asheville, NC. Edmund Braly, Norman, OK. Steven Hefner. Lorne Sheren, New Vernon, NJ

And thanks to these donors in 2024:

Jim Lara, Joseph Stadelmann, Dixon Smith, Barry Warner, Wayne Mudge, Joseph Vandenbosch, Ian Campbell, Jay Apt, John Kimmons, Derek Rowan, Michael Maya Charles, Ron Horton, Lauren McGavran, Gerald Magnoni, Amy Haig, Rod Partlo, Brent Chidsey, Mard Sasaki-Scanlon, SABRIS Aviation (Dave Dewhirst), Edmund Braly, Joseph Orlando, Charles Lloyd, Michael Morrow, Abigail Dang, Thomas Jaszewski Danny Kao, Gary Garavaglia, Brian Larky, Glenn Yeldezian, David Yost, Charles Waldrop, Robert Lough. Gilbert Buettner. Panatech (Henry Fiorientini). Dale Bleakney. Mark Kolesar. John Winter. Donald Bowles. David Peterson. Bill Abbatt

NEW THIS WEEK: Bruce Jacobsen, Denny Southard

Pursue Mastery of Flight (TM)

Thomas P. Turner, M.S. Aviation Safety

Flight Instructor Hall of Fame Inductee

2021 Jack Eggspuehler Service Award winner

2010 National FAA Safety Team Representative of the Year

2008 FAA Central Region CFI of the Year

FLYING LESSONS is ©2024 Mastery Flight Training, Inc. For more information see www.thomaspturner.com. For reprint permission or other questions contact [email protected].