Topics this week: > Admitting it can > We don’t know why > Everyone does it, it’s inconvenient, nothing bad happened

FLYING LESSONS uses recent mishap reports to consider what might have contributed to accidents, so you can make better decisions if you face similar circumstances. In most cases design characteristics of a specific airplane have little direct bearing on the possible causes of aircraft accidents—but knowing how your airplane’s systems respond can make the difference in your success as the scenario unfolds. So apply these FLYING LESSONS to the specific airplane you fly. Verify all technical information before applying it to your aircraft or operation, with manufacturers’ data and recommendations taking precedence. You are pilot in command and are ultimately responsible for the decisions you make.

FLYING LESSONS is an independent product of MASTERY FLIGHT TRAINING, INC.

Pursue Mastery of Flight™

This week’s LESSONS:

Award-winning flight instructor and FLYING LESSONS reader Peg Ballou sent me this link to a tragic story, and wrote:

Here is an odd one for you. And no one’s talking about it. Here is a helicopter pilot who went out on the morning of his wife’s funeral and hit wires and killed himself. My thinking is that he was impaired because of emotion and should not have been flying.

From the article:

Anthony “Andy” Jones was supposed to say goodbye to his wife of 30 years during funeral services Friday night, a week after she died. Instead, the helicopter he was flying that morning struck an electrical line and crashed into the Mogadore Reservoir in Portage County [Ohio]. His body was recovered in the water a couple hours later.

The helicopter, a Schweizer 269C, crashed into the Mogadore Reservoir near state Route 43 in Suffield Township at about 7 a.m., according to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Only the pilot was on board the helicopter at the time of the crash. Suffield Township Fire Chief Bob Rasnick confirmed the pilot, Jones, 52, of North Royalton, died and was recovered from the water.

The OHSP [Ohio State Highway Patrol] said they are leading with investigation with the assistance of the National Transportation Safety Board. OSHP said the helicopter remains in the water and that it could take up to a week before the aircraft is removed. Lt. Craig Peeps of Portage County Hazmat said the helicopter company and its insurance need to coordinate to pull it out of the reservoir.

OHSP said they don’t know the purpose of the flight at this time. Based on preliminary investigation, it took off from Medina, stopped to refuel and took off again before the crash. The agency added that the helicopter broke one wire before hitting the water and that the wire was not carrying a current. No surrounding homes lost power from the crash. Ohio Edison has since secured the wire.

The article provides more details:

A visitation for Amy [the pilot’s deceased wife] was scheduled for 5-7 p.m. [that same day] with a service beginning at 7 p.m. The first call reporting the crash came in at 7:11 a.m. A team of divers started their search at 9:29 a.m., located the helicopter at 9:33 a.m. and recovered Jones at 9:35 a.m.

Flight instructor Peg writes:

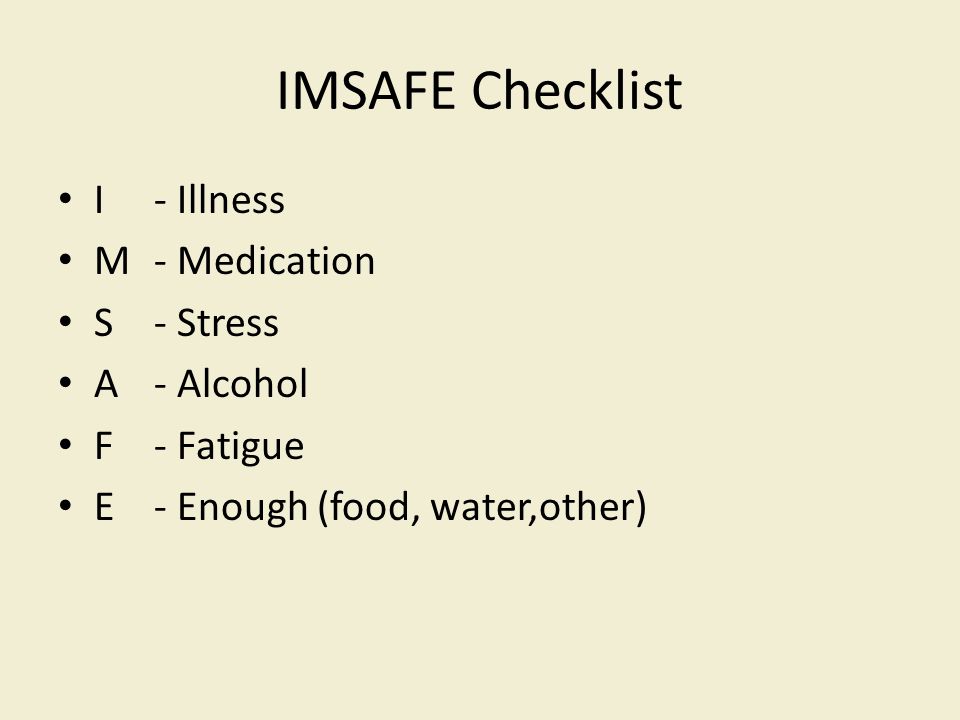

We teach IMSAFE but the E is [depending on the source] eating/emotions/energy (take your pick). Emotions sap energy. This brings to mind the AOPA video long ago—“No Greater Burden”—of a man who flew his seaplane two weeks after his mom’s death, landing on hard surfaces for landing practice, and then at a lake where he omits retracting his landing gear. The plane flipped and while he was rescued, his six-year old was killed. His summary statement is roughly, “I didn’t realize how much my mother’s death affected me.”

I have used this example with my students and how I took myself out of the cockpit when my mother died. Shortly afterwards a student did the same when his grandfather died. I praise them for such good decision making. I saw the negative result of this when a checkride candidate insisted on taking a ride despite his uncle being killed shortly before. We just don’t realize what a loss like that can do to us.

In the article I sent you you’ll note the man was killed the very morning of the visitation hours for his wife. What stress and loss was he experiencing, and how did that impact his decision making? We will never know, but what double grief his family bore.

****

The hard part is that the person who must self-evaluate his/her current fitness for flight—that would be all of us—is the person least capable of making an objective assessment when it’s needed most. The “E” in IMSAFE is probably the hardest for self-awareness…even the experts don’t agree on what the E means.

Assuming it stands for Emotion (or emotion is evaluated under S for Stress), it makes sense to think about situations that might negatively affect your fitness for flight now, when (presumably) you are not affected by crippling stress or emotion. Set some basic rules to help you make the evaluation later when you might need it. One might be: Am I affected by recent loss that came as a shock?

Readers, what might be other basic rules for you? Do you have techniques that work for you? Have you ever had to make such a preflight decision? Did you make it, and if not, how did it come out?

It’s hard to detect when emotion might adversely affect safety. It’s even harder to admit it can.

Peg Ballou is AOPA’s 2025 Best Instructor for the Great Lakes region. Her company Ballou Skies Aviation in Bucyrus, Ohio is this year’s Great Lakes regional Best Flight School. Congratulations, Peg, and thank you for your guest editorial as this week’s LESSON.

Questions? Comments? Supportable opinions? Let us know at [email protected].

Debrief

Readers write about previous LESSONS

Reader/instructor Brian Sagi writes about last week’s LESSONS on the effects of weight and balance on aircraft performance:

Manufacturers want to delivery capable airplanes that can carry a lot. All being equal, they will set the highest gross weight they can for the airplane, while meeting all the certification requirements for the airplane on time and on budget. We pilots have no way of telling what constraint led the manufacturer to set the weight limit. It could be structural strength, it could be fatigue that builds over time and can lead to premature airframe or component failure, it could be angle of attack in climb limits needed to ensure that ice does accumulate on the bottom, unprotected, side of the wing (for Flight into Known Ice airplanes). It could also be any of a multitude of other reasons why, with a higher gross weight, the airplane manufacture was not able to demonstrate to the FAA compliance with certification requirement. It is folly to assume that “everything will be OK when we operate over weight.”

That’s a point I try to make in all sorts of cases where pilots ask me to comment on their justification for exceeding airplane limitations—that we don’t always definitively know why a limitation exists, so we don’t have any reason to doubt its wisdom. I’m asked surprisingly frequently, and I think they’re trying to trap me into agreeing with them so they’ll quote me on it later…like my opinion supersedes engineering. Thanks, Brian.

Reader and monthly support Eric Hoel asks some questions:

I enjoyed this week’s installment quite a bit. It was very interesting and thought provoking (as is usually the case).

I am looking forward to your future treatment of the CG/overweight discussion. On a related note, one of the things that I’ve always been a bit puzzled by was how on a Bonanza (I have a N35), why does adding tip tanks increase your available load (gross weight)? How much does it affect your CG envelope? I’ve head discussion on BeechTalk and elsewhere that this relates to the Bonanza being certified in the utility category, whereas tip tanks revert it back to the normal category. Hearing your authoritative take would be most appreciated.

Your 1961 N35 is indeed certified in the Utility category, which means it can withstand up to 4.4G without stress damage. At a maximum takeoff weight of 3125 pounds it is capable of handling up to 13,750 pounds (3125 x 4.4). If that airplane is recertified in the Normal category it is only required to withstand 3.8Gs, or 11,875 pounds (3125 x 3.8). This leaves an extra 1875 pounds to the structure’s actual limit (13,750 – 11,875). Divide that by 3.8 (the Normal limit) and you have 493 more pounds to add to the airplane’s original weight and remain in the Normal category. Why during certification this is reduced to 200 pounds (the usual gross weight increase for tip tanks) I do not know; perhaps FAA required some percentage required as a margin, or there was some other expedient available to the tip tank developer that kept the increase to that level.

I’m sure there’s more to it than this (another case of not knowing all the details of a limitation), but it’s at least a partial explanation of how a gross weight increase (GWI) can be certified when reverting to a lesser stress certification at weights above the airplane’s originally certificated maximum.

How does this affect the CG envelope? Adding additional weight does not extend the envelope fore or aft. I happen to know that in your airplane the arm of the main fuel tanks in the wing leading edge is 74 inches aft of the datum, and fuel in the tip tanks is at 86.7 inches aft of data (confirm that in case your tip tank STC is different). That means when you put fuel in the tips the total airplane CG moves aft. As you burn or transfer fuel out of the tips the CG moves forward. Your STC Supplement (required to be in the Pilot’s Operating Handbook) will show an extension above the original loading envelope diagram for weights above the original maximum gross weight up to the new MGW as approved for the tip tank modification.

On another note, I recently completed my first true cross country (KREI Redlands to KJZI Charleston Exec and back). I filed IFR the entire trip except for the final leg between Tucson and Redlands. I flew it VFR with flight following. The reason for doing so was that there was forecast icing at the typical routing levels between Tucson and Redlands (e.g., 9000 – 13,000 MSL). I currently do not have oxygen onboard, so flying above was not possible (ignoring the sketchiness of a fast descent through possible icing, etc.). Flying VFR at 6500 MSL worked very nicely. I found it interesting that IFR and VFR can sometimes be quite useful this way.

It’s great how flexible our system can be and still help us be safe. I’m glad you enjoyed your flight.

On a final chatty note, I would be interested to hear what you think about onboard oxygen – bottled vs. concentrators, etc. Any guidance here?

I have no personal experience with oxygen concentrators. I have heard Naval aviator, flight surgeon and Aviation Medical Examiner Keith Roxo of wingmanmed.com talk about them during a presentation, however. He said oxygen concentrators work well at lower altitudes, but since they depend on a certain amount of ambient oxygen to be able to concentrate it to a higher delivery rate, he does not think they can provide sufficient oxygen flow at the altitudes pilots need supplemental oxygen. If any reader has additional information please send it and I’ll provide an update. Thanks for the conversation, Eric.

Frequent Debriefer and cabin-class aircraft instructional expert Dave Dewhirst wraps it up this week:

This is a follow-up to your discussion on operating over [maximum] gross weight.

Several years ago, as an Aviation Safety Counselor, I received a call from the FSDO [FAA Flight Standards District Office] to have a talk with a pilot on an overweight issue. The pilot was seen with four normal size adults exiting a popular high-performance pressurized single. Including the pilot, that put five people in the airplane. FlightAware showed the flight was about two hours in length. The fuel added to the airplane after landing showed the airplane departed with close to full fuel. This put the airplane about 600 pounds over GWT [maximum gross weight] at takeoff.

The pilot was very high time and a friend. His response was astounding. First, the flight was completed without incident, so what? Second, people fly over GWT all the time. Third, the airplane was useless if it were necessary to remain within the GWT limitation. I suggested a larger airplane.

Another story. We recently purchased another Cessna 421 that spent four years in Thailand. The paperwork for the ferry tank system was in the logbooks. The seats were removed and a large ferry tank added. The special operational approval showed an allowable GWT increase. Normal GWT for a C421 is 7,450 Lbs. This ferry flight was approved for a 9,000 Lb. GWT. A long list of operational limitations was included. I hate to think about all the things that could have gone wrong, including an engine failure or an emergency landing at that weight. This kind of situation is normal for extended ferry flights. The sad part of this story is that some operators take this information and use it as justification to operate their own airplane above GWT.

Your analysis of all the performance reasons not to operate above GWT is on target.

I was able to get confirmation that operating an aircraft beyond its Type Certified Limitations, including operating over GWT, could be a consideration in denying insurance coverage. However, an accident would probably have to be involved. Coverage would not necessarily be cancelled or not renewed just for that issue. A history of pilot violations would be a factor. For example, there is an accident in the news about a pilot who pulled the wings off of a Malibu. Using data from FlightAware and a whiz-wheel, it can be demonstrated the pilot exceeded Vne. Insurance coverage was one of the items discussed.

You’re right, the insurance company would not likely have a way to find out about operation above maximum gross weight unless there was a claim and the weight and balance was calculated by investigators…or reliable witnesses recount an obvious overload condition like your first example. The three rationalizations you report—everyone does it, it isn’t convenient, nothing bad happened this time—are common.

Here’s another one, a rationalization I had pitched to me asking for validation and approval not once, but on three different occasions from the same pilot:

Most aircraft accidents happen during takeoff and landing. I volunteer to fly doctors to and from a short, remote airstrip in Baja Mexico, from a base in central California. We load up with passengers and equipment along with baggage for several days. To load the airplane within limits I must significantly reduce the fuel load, and that means I have to stop for fuel in southern California before continuing to our home base where U.S. Customs is also available.

Since the risk is highest during takeoff and landing, it’s safer to fill the tanks and operate the airplane well above its maximum gross weight so I can make the trip nonstop and eliminate the extra landing and takeoff that exposes us to the greatest hazard. Do you agree?

No, I don’t. Even more so since that means an overweight takeoff from a short dirt strip on the northbound trip. But even southbound off a long runway, no, I don’t agree.

That’s what’s going on out there. We don’t know everything about the reason for limitations. But we do know is that, if flying an aircraft outside its approved envelope, it won’t perform as expected. If anything out of the ordinary happens, you won’t have the margins you may need to save your life (and those of your passengers). Resist rationalization. Thank you as always, Dave.

More to say? Let us learn from you, at [email protected]

Share safer skies. Forward FLYING LESSONS to a friend.

Please help cover the ongoing costs of providing FLYING LESSONS through this

secure PayPal donations link. Or send a check made out to Mastery Flight Training, Inc. at 247 Tiffany Street, Rose Hill, Kansas USA 67133. Thank you, generous supporters.

“[My donation is] long overdue support for you and your incredible work. Thanks as always for providing the best continuing General Aviation education in the industry.”

– Andrew Urban, Sun River, Wisconsin

Thank you, Andy, for your continued contributions toward the costs of hosting and delivering Mastery of Flight.(TM) And thank you to all these FLYING LESSONS readers:

Thank you to our regular monthly financial contributors:

Steven Bernstein, Montclair, NJ. Robert Carhart, Jr., Odentown, MD. Greg Cohen, Gaithersburg, MD. John Collins, Martinsburg, WV. Dan Drew. Rob Finfrock, Rio Rancho, NM. Norman Gallagher. Bill Griffith, Indianapolis, IN. Steven Hefner, Corinth, MS; Ellen Herr, Ft Myers, FL. Erik Hoel, Redlands, CA. Ron Horton. David Karalunas, Anchorage, AK. Steve Kelly, Appleton, WI. Karl Kleiderer. Greg Long, Johnston, IA. Rick Lugash, Los Angeles, CA. Richard McCraw, Hinesburg, VT. David Ovad, Resiertown, MD. Steven Oxholm, Portsmouth, NH. Brian Schiff, Keller, TX. Paul Sergeant, Allen, TX. Paul Uhlig, Wichita, KS. Richard Whitney, Warrenton, VA. Jim Preston, Alexandria, VA. Johannes Ascherl, Munich, Germany. Bruce Dickerson, Asheville, NC. Edmund Braly, Norman, OK. Steven Hefner. Lorne Sheren, New Vernon, NJ. “The Proficient Pilot,” Keller, TX. Ed Stack, Prospect Heights, IL. Kynan Sturgiss, Hereford, TX. Bluegrass Rental Properties, LLC, London, KY. John Foster. Joseph Victor, Bellevue, WA. Chris Palmer, Irvine, CA. Barry Warner, Yakima, WA

NEW THIS WEEK: Todd LeClair, Cadiz, KY

Thanks also to these donors in 2025:

John Teipen. N. Wendell Todd. David Peterson. Jay Apt. SABRIS Aviation/Dave Dewhirst. Gilbert Buettner. David Larsen, Peter Baron, Glen Yeldezian, Charles Waldrop, Ian O’Connell, Mark Sletten, Lucius Fleuchaus. Thomas Jaszewski. Lauren McGavran. Bruce Jacobsen, Leroy Atkins, Coyle Schwab, Michael Morrow, Lew Gage, Panatech Computer (Henry Fiorentini), John Whitehead, Andy Urban, Wayne Colburn

Pursue Mastery of Flight(TM)

Thomas P. Turner, M.S. Aviation Safety

Flight Instructor Hall of Fame Inductee

2021 Jack Eggspuehler Service Award winner

2010 National FAA Safety Team Representative of the Year

2008 FAA Central Region CFI of the Year

FLYING LESSONS is ©2025 Mastery Flight Training, Inc. For more information see www.thomaspturner.com. For reprint permission or other questions contact [email protected]