Pursue Mastery of Flight™

This week’s LESSONS:

What Went Right? What Went Wrong?

From an NTSB preliminary report (CEN24LA020):

On October 23, 2023, at 1611 central daylight time, a Piper PA-46-350P (turboprop conversion Piper Mirage) was involved in an accident near Pierre, South Dakota.

According to the pilot, before takeoff from the Pierre Regional Airport (PIR), Pierre, South Dakota, the airplane was fueled with 10 gallons of fuel for a total of 100 gallons on board for the planned flight to Steamboat Springs, Colorado. The pilot reported no anomalies were noted during the engine start, takeoff, and initial climb. About 10,000 ft mean sea level (msl), air traffic control cleared the pilot to Flight Level 220. While climbing through 11,000 ft msl, the engine “abruptly stopped; rolled back.” The pilot noted no cockpit warning or abnormal indications before the loss of engine power. The pilot declared an emergency and then executed a 180° turn back to PIR.

During the emergency descent, the pilot attempted to restart the engine, but the restart was unsuccessful, and he feathered the propeller. At some point during the descent, the airplane also lost electrical power. Unable to make PIR, the pilot attempted a forced landing to bluffs and rolling terrain (see Figure 1). The airplane came to rest upright and sustained substantial damage to the fuselage and both wings.

After an unexplained loss of power from the ultra-reliable PT6A-35 turboprop engine, the pilot appears to have done everything right:

- Fly the aircraft;

- Aim somewhere (not wasting time flying away from a good option before selecting a landing target);

- Complete the emergency procedure checklist while still flying the airplane and aiming toward your target;

- Reassess the target and change targets only if necessary.

- Touch down wings level, under control at the slowest safe speed, and in a retractable gear airplane, with the landing gear up.

Even so, something went terribly wrong. The NTSB preliminary report continues:

After the accident, the pilot observed the passenger, who was seated in a rear forward-facing seat, was barely conscious. After checking the passenger’s vital signs, the pilot performed cardiopulmonary resuscitation until first responders arrived on-scene.

The pilot sustained serious injuries, and the passenger sustained fatal injuries. Post-accident examination of the airplane at the accident site revealed no external anomalies or malfunctions, and the airplane was retained for further examination.

The final investigation will no doubt reveal the causes of injury and death. All indications are this was a relatively low-speed, controlled impact. Were seat belts and shoulder harnesses used correctly? Did restraint system connections break, or the belt webbing itself fail? Did the passenger die of a physical condition triggered by the stress of the emergency but not as a direct result of impact forces? Did the airplane hit something not visible in the NTSB photograph that caused it to decelerated extremely rapidly, imparting forces that exceeded human tolerance or the design load of the restraint systems?

As Aviation Safety’s Mike Hart wrote in “The Art of Crashing”:

Deceleration is measured in multiples of the force of gravity, or G. During high-speed crashes, it is pretty easy to generate accelerations in the range of 25 to 50G. Unfortunately, that also is the range where severe injury or death is likely. The art of a good crash is to reduce G loads as much as possible. You do this by spreading the energy over as much distance as you can. Pardon the double entendre, but you want to leave a long skid mark.

In steep terrain, this means having the aircraft oriented to as low an impact angle as possible before making contact. Easier said than done, but a low contact angle will help you “skip” off the surface obstacles. Also, if you can aim for obstacles that have potential to give (tree tops, vegetation) vs. obstacles that don’t give (rock faces, structures).

How much of a difference will skidding, bouncing or dissipating energy over a distance make? A lot. An aircraft traveling at 60 knots coming to a full stop in one foot (as when hitting a cliff face head-on), will generate 160G. It is not a survivable crash. In fact, at that G-loading, bones will break and the human body becomes a liquid—it is not pretty.

Spreading that same energy out over 10 feet drops the deceleration to 18G, which is bad, but survivable. Spreading the stopping distance to 30 feet takes you down to 5G, and if you can stretch the distance to 50 feet, where the deceleration is only 3G, you may have actually had worse turbulence than that.

Again, speed matters. If your initial speed was 80 knots instead of 60 knots, your 50-foot stop will be 5.5G and your 30-foot stop is 10G. Anything you do that will gain you a bit of stopping distance will reduce the crash loading. G-loading isn’t strictly about initial speed, it also has a huge amount to do with how quickly you lose that speed.

Note the above deceleration calculations are not off-the-shelf numbers you can count on for your particular crash. They assume a uniform deceleration from first contact to complete stop.

The published Best Glide speed for a PA46-350P in Piper’s Information Manual is 90 knots indicated airspeed. The Power Off Landing checklist states: “When [the] field can easily be reached slow to 77 KIAS for shortest landing” performance. Mike Hart’s comments about an 80 knot touchdown speed would seem to apply.

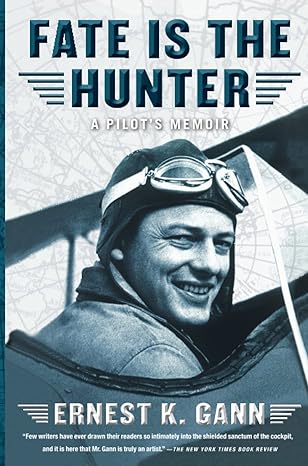

You can do everything right and still not have a good outcome. I hate to say it, but there’s a small element of luck involved even if we’ve made all the right risk management choices. I’m a big fan of Ernest Gann’s Fate is the Hunter, in fact I give a copy of Fate and a copy of Stick and Rudder to friends and mentorees upon earning their Private Pilot certificate. But I do not like the inference that flying is, as Gann puts it, an endless war against an unhuman force we can only hope to outrun, that fate alone—luck—determines whether we (and our passengers) enjoy a long life of safe, enjoyable flying. I believe instead that the better we are at aeronautical decision making, risk management and physical flying skills, the less likely fate will determine our survival. Doing everything right doesn’t assure success—that’s part of the risk we must consciously accept to fly. But being prepared and doing everything right goes a very long way toward reducing that risk.https://www.amazon.com/Fate-Hunter-Ernest-K-Gann/dp/0671636030

If you don’t do everything right there is much less chance of a good outcome. That’s a risk we don’t have to accept. It’s why we train, and read, and run scenarios in our heads and practice procedures for muscle memory in our cockpit—so if something bad happens we can deliver the very best outcome possible under the circumstances…minimizing as much as possible any reliance on luck.

Questions? Comments? Supportable opinions? Let us know at [email protected].

Debrief:

Readers write about recent FLYING LESSONS:

Readers write about last week’s LESSONS from one of my past years’ Thanksgiving flight home:

Great post Tom. We are all human with the same weaknesses and frailties. Launching into bad weather to get to a planned event or to home, on return, is a siren song. This time of year with Thanksgiving and Christmas coming up is when we see a lot of “get there itis accidents”. You illustrate well the way we justify amending our personal minimums. Always have a Plan B! Airline tickets, drive, etc. We drove this week from Florida to St. Louis rather than fly the two of us. I was not willing to rush some maintenance to use our plane. There will always be tomorrow if everyone adopts your recommendations. – Jeff Edwards

Hello Tom, I enjoyed your ADM article. On one of our European tours we were sitting in a room in Cambridge UK, wanting to cross the English Channel to get our France tour underway. but not surprisingly, the weather was not cooperating. We had already delayed our departure from the UK by 1 day and were now looking at a 2nd day’s delay. So getting-there-itis was in the air.

Flying VFR, we had spent the last couple of hours checking the METARS at the various airports en route and at the destination. When we saw an improvement we were tempted to “go” but then the next METAR would be worse and we would decide to wait another hour to see if it had improved. Needless to say we had a scenario that could have led to a questionable ADM.

In the end we did not go, but the lesson for me was a comment made by one of the group’s pilots, one with much more experience that most of us in the room. and he said that if you are sitting there looking at METARS, hoping to see enough of an improvement to go, then you should stay put. You should only go if the METARS are showing a very clear improvement trend. A simple (and obvious?) rule that has stayed with me and has proven to be sage advice. – Clare McEwan

Hi Tom, Great edition this week. I remember you sharing this trip before, but it’s such a good illustration of how subtle the pressure can be to complete a “mission.” And how we often assume passengers care much more than they really do.

The key (in my opinion) is to create decision-making circuit breakers. Just like an electrical circuit breaker prevents a small problem from becoming a big one, a good mental one can catch a small error before it spirals into a fatal accident. Instead of expecting flawless self-awareness, we should instead build in predefined events that lead to an automatic diversion. In the helicopter world, many operators use a two strikes rule: if you descend or reduce power twice on a flight (go down/slow down), you must land immediately. It’s a sign you are probably scud running and about to get in real trouble. What is an example for airplanes?

Aviation long ago figured out that we need to have fault tolerant systems – we should expect humans to make mistakes and have avionics/checklists/CRM to catch them and fix them. Same goes for weather decisions. – John Zimmerman

Thank you, everyone!

Reader Ed Loskill continues our ongoing discussion of evaluating takeoff performance including the 70/50 Rule:

Hi Thomas, I appreciate and enjoy your FLYING LESSONS. I would like to add this article to the 70/50 rule in take-off roll considerations. Thought it adds some good analysis and added what-if’s.

That’s a slant on the 70/50 rule I frankly have not considered. My emphasis using this estimation tool is a check against initial takeoff performance to detect a lack of acceleration that should prompt an immediate abort. In many cases of runway overrun in an attempted takeoff, failure to clear obstacles after liftoff, or an aerodynamic stall after takeoff credible witnesses report the airplane did not seem to be performing during takeoff, often with the witness reporting the airplane lifted off much farther down the runway than “normal.”

In the article Alec Myers discusses nonlinear acceleration, a valid concern. He sees the 70/50 Rule as flawed because of uneven and unpredictable runway surfaces. His thesis is that reaching 70% of the takeoff speed by the time you’re halfway through your predicted ground roll distance does not guarantee you’ll still reach liftoff speed at your liftoff point, nor does it affirm an aggressive abort will come to a stop within the remaining runway distance.

My use of the 70/50 rule is to trigger an abort up to that point if the airplane is not getting the expected acceleration and you should immediately abort…but not necessarily that the takeoff is assured. It’s a performance gate with a reasonably objective measurement. If you are at 70% of takeoff speed at 50% of the computed takeoff distance you can keep trying, but if you are notmeet the 70/50 Rule you should immediately reject the takeoff. I’ve found the 70/50 Rule especially helpful when departing at a high density altitude (which is not normal for me).

Myers’ article is excellent and deserves at least equal consideration, but it provides no objective replacement for confirming takeoff performance during the ground roll, especially under unusual circumstances. Readers, please read the article. Then tell me how you would evaluate takeoff performance, say departing Colorado Springs, Colorado (KCOS, elevation 6187 MSL) on a warm day when density altitude is over 9000 feet? Thank you, Ed.

More to say? Let us learn from you, at [email protected].

Share safer skies. Forward FLYING LESSONS to a friend

Please help cover the ongoing costs of providing FLYING LESSONS through this secure PayPal donations link. Or send a check made out to Mastery Flight Training, Inc. at 247 Tiffany Street, Rose Hill, Kansas USA 67133.

Thank you, generous supporters.

Special thanks to these donors for helping with the Mastery Flight Training website rebuild and beyond:

Karl Kleiderer, Jeffery Scherer, Ken Newbury, William Eilberg, Wallace Moran, Lawrence Peck, Lauren McGavran, Stanley Stewart, Stu and Barbara Spindel, Danny Kao, Mark Sanz, Wayne Mudge, David Peterson, Craig Simmons, John and Betty Foose, Kendell Kelly, Sidney Smith, Ben Sclair, Timothy Schryer, Bruce Dickerson, Lew Gage, Martin Pauly, Theodore Bastian, Howard Greenberg, William Webber, Marc Dullude, Ian O’Connell, Michael Morrow, David Meece, Mike Gonce, Gianmarco Armellin, Mark Davis, Jason Ennis, William Moore, Gilbert Buettner, Don Denny, John Kolmos, LeRoy Cook, Mark Finklestein, Rick Lugash, Tom Carr, John Zimmerman, Lee Perrin, Bill Farrell, Kenneth Hoeg, William Jordan Jr., Mark Rudo, Boyd Spitler, Michael Brown, Gary Biba, Meaghan Cohen, Robert Chatterton, Lee Gerstein, Peter Tracy, Dan Drew, David Larson, Joseph McLaughlin, Nick Camacho, Paul Uhlig, Paul Schafer, Gary Mondry, Bruce Douglass, Joseph Orlando, Ron Horton, George Stromeyer, Sidney Smith, William Roper, Louis Olberding, George Mulligan, David Laste, Ron Horton, John Kinyon, Doug Olson, Bill Compton, Ray Chatelain, Rick McCraw, David Yost , Johannes Ascherl, Rod Partio, Bluegrass Rental Properties, David Clark, Glenn Yeldezian, Paul Sherrerd, Richard Benson, Douglass Lefeve, Joseph Montineri, Robert Holtaway, John Whitehead; Martin Sacks, Kevin O’Halloran, Judith Young

Thanks to our regular monthly financial contributors:

Steven Bernstein, Montclair, NJ. Robert Carhart, Jr., Odentown, MD. Randy Carmichael, Kissimmee, FL. James Cear, South Jamesport, NY. Greg Cohen, Gaithersburg, MD. John Collins, Martinsburg, WV. Paul Damiano, Port Orange, FL. Dan Drew. Rob Finfrock, Rio Rancho, NM. Norman Gallagher. Bill Griffith, Indianapolis, IN. Steven Hefner, Corinth, MS; Ellen Herr, Ft Myers, FL. Erik Hoel, Redlands, CA. Ron Horton. Robert Hoffman, Sanders, KY. David Karalunas, Anchorage, AK. Steve Kelly, Appleton, WI. Karl Kleiderer. Greg Long, Johnston, IA. Rick Lugash, Los Angeles, CA. Richard McCraw, Hinesburg, VT. David Ovad, Resiertown, MD. Steven Oxholm, Portsmouth, NH. Brian Schiff, Keller, TX. Paul Sergeant, Allen, TX. Ed Stack, Prospect Heights, IL; Robert Thorson, Reeders, PA. Paul Uhlig, Wichita, KS. Richard Whitney, Warrenton, VA. James Preston, Alexandria, VA.

Pursue Mastery of Flight

Thomas P. Turner, M.S. Aviation Safety

Flight Instructor Hall of Fame Inductee

2021 Jack Eggspuehler Service Award winner

2010 National FAA Safety Team Representative of the Year

2008 FAA Central Region CFI of the Year

FLYING LESSONS is ©2023 Mastery Flight Training, Inc. For more information or to subscribe see www.thomaspturner.com. For reprint permission or other questions contact [email protected].