FLYING LESSONS uses recent mishap reports to consider what might have contributed to accidents, so you can make better decisions if you face similar circumstances. In most cases design characteristics of a specific airplane have little direct bearing on the possible causes of aircraft accidents—but knowing how your airplane’s systems respond can make the difference in your success as the scenario unfolds. So apply these FLYING LESSONS to the specific airplane you fly. Verify all technical information before applying it to your aircraft or operation, with manufacturers’ data and recommendations taking precedence. You are pilot in command and are ultimately responsible for the decisions you make.

FLYING LESSONS is an independent product of MASTERY FLIGHT TRAINING, INC.

Pursue Mastery of Flight™

This week’s LESSONS

The NTSB recently posted this preliminary accident report:

On December 1, 2024, at 1821 central standard time, a Piper PA-28R-200 airplane…sustained substantial damage when it was involved in an accident near Boscobel, Wisconsin. The flight instructor and pilot receiving instruction were not injured….

This was well after civil twilight and in full night conditions. The NTSB continues:

According to the flight instructor, they were established in cruise on the return leg of a night cross-country instructional flight at 9,000 ft mean sea level, when they noticed an odor in the cockpit. The flight instructor noted no issues in the cockpit, and adjusted the heat control, in which the odor diminished.

The flight instructor then noticed an opaque windscreen and immediately thought they had encountered icing conditions. The flight instructor contacted air traffic control (ATC) and requested a lower altitude.

Good instructor response to a perceived problem. But is a pattern emerging? Read on.

Utilizing a flashlight, the flight instructor illuminated the windscreen and noticed a “brown river” completely obscuring their forward visibility. The cockpit oil pressure gauge indicated little to no oil pressure.

Night VFR and a catastrophic loss of engine oil. What would you do? Here’s what happened next:

The flight instructor declared an emergency with ATC and took the airplane controls from the pilot receiving instruction. The flight instructor located the nearest airport to attempt a forced landing. During the forced landing to the airport with the windscreen covered in engine oil, the airplane impacted terrain adjacent to the runway surface, bounced, and came to rest upright. The airplane sustained substantial damage to the right horizontal stabilator.

Declaring an emergency does not appear to have had an impact on the outcome of this event. Still, I applaud the instructor for doing so. In addition to alerting controllers to your problem and getting priority handling if conflicts occur, I believe the greatest benefit of formally declaring an emergency is that it puts you in the emergency mindset. It reinforces the gravity of the situation and empowers you to make the decisions necessary to get the airplane on the ground safely, without hesitation or trying to rationalize away the indications. Being in the emergency mindset makes expediting a landing your primary objective…you give yourself permission not to be heroic.

Neither the student nor the instructor was hurt, according to the NTSB. The preliminary report concludes:

Postaccident examination of the airplane revealed engine oil on the top engine cowling, windscreen, and empennage. No evidence of an uncontained engine failure was noted. The airplane was retained for further examination.

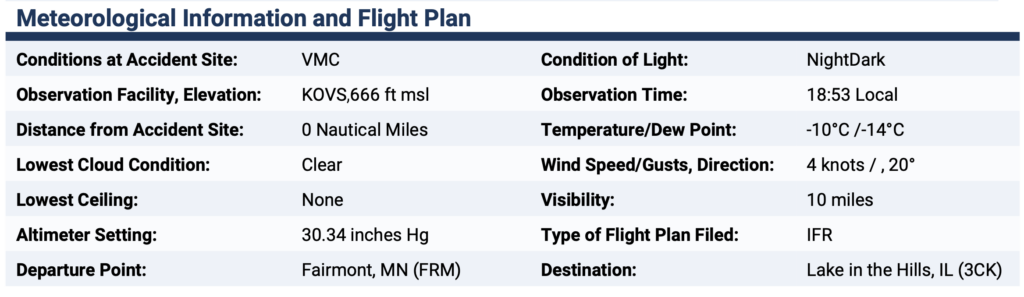

Weather information from the NTSB preliminary report:

Wait, that’s not what I was expecting to read. No uncontained engine failure, the NTSB says.

Cold, clear skies on an IFR flight plan and light surface winds…sounds like a great time to teach instrument flight, at least after preflight and starting in the very cold conditions. But it’s very cold and you’re running the cabin heat. You smell an unusual odor and your first thought is it’s coming from the heater—so you shut it off. What are some implications of that?

- Was there any carbon monoxide contamination? How can you be sure?

- Do you have a CO alarm in the airplane? If you carry an old-school “dot”-type CO warning and it’s discolored the level of contamination is already enough to require an immediately landing.

- Do you use a pulse oximeter? Pulse-ox devices use a low-power light beam to measure the reflectiveness of your blood. If your blood is carrying less oxygen less of the light reflects back to the sensor, and the readout provides a calibrated percentage. But carbon monoxide is denser than 02…and your blood attaches to CO molecules more readily than it does 02 (which is why CO is so dangerous, it displaced oxygen in your blood).

- CO will show a false high percentage on a pulse oximeter, suggesting that everything is OK when it is not. You should know the percentage you should expect to see at your current altitude; if the percentage is much higher than normal that itself is a possible sign of CO exposure.

- Ventilate the cabin by opening windows and vents to reduce the CO concentration. But that may make if dangerously cold, since you’ve turned off the cabin heat. You may need to land right away to avoid the dangers of extreme cold.

- If it was CO exposure, you need to land as soon as possible. Not as soon as practical, as soon as possible. But that might put you on the ground at an airport where you’re exposed to the extreme cold, possibly for a long time. Might you ask Air Traffic Control (ATC) to alert first responders to meet you at your diversion airport just in case, but if for no other reason to rescue you from the cold?

- If it was CO exposure, most sources recommend delaying flight for at least 24 hours to restore your blood’s ability to carry sufficient oxygen to support flight.

What if your airplane has a calibrated CO sensing alarm and you have a pulse oximeter that reads as you’d expect at 9000 feet? Turn off the heater and you should consider:

- How high was the CO level? Do you still need to get on the ground at the first possible opportunity, again asking ATC to send the paramedics to meet you to avoid frostbite or freezing to death on the ground.

- If exposure was not a problem and you remain aloft, the temperature aloft is probably dangerously low. If the temperature lapse rate is standard, -10°C on the ground at close to 1000 MSL means -26°C at 9000 feet. There may have been a nonstandard lapse rate and it’s not unusual to have an inversion aloft in early evening on a clear, calm winter’s night. But these early-night inversions don’t usually extend to 9000 feet, and even if it did the temperature aloft that night was dangerously cold for any period of exposure without cabin heat.

- So turning off the heater in such conditions—even if you can confirm there was no CO exposure—should be a land as soon as practical situation to avoid the physiological effects of extreme cold.

We know from the NTSB that something else was happening. Shortly after turning off the heater—perhaps very shortly after, the report doesn’t say—the instructor noticed he/she could not see through the windscreen. The instructor contacted Air Traffic Control and requested a lower altitude. Consider this:

- The NTSB states skies were clear, but that was a localized report and there’s a chance conditions were different elsewhere. In this case, the instructor and student should have known that clouds were possible along the route of flight (I’d have made the instrument student brief me on weather before takeoff). Night flight in clouds in subfreezing temperatures should be a no-go item in an airplane not certificated for flight in icing conditions…and for that matter the pilot of an ice-certified airplane should take pause if night icing conditions are forecast.

- It may have been so cold that airframe ice was unlikely in some types of clouds. That doesn’t change a night-IMC-ice=no-go in my opinion, but that’s me. In such conditions snow might bounce off the airframe with accumulation…but impact snow can plug air inlet filters and choke off the engine’s air supply.

I suspect, however, that the Pilot Receiving Instruction (PRI) and the CFI had briefed the weather and conditions were as the NTSB reports in the forecast. The instructor’s initial thought “ice” was probably a momentarily confused (and understandable) response to the combination of “it’s cold” and “the windshield is opaque.”

That’s probably why the instructor shone a flashlight on the windscreen and discovered what appeared to be engine oil (not ice) causing the obscuration.

From there CFI and PRI appear to have done a great job of finding a nearby airport, maneuvering with the imminent threat of power loss, which apparently did not occur. It seems to the best of their ability, without forward visibility in night skies, they got the Arrow on the ground without being injured. The airplane, which suffered “substantial” damage, was expendable.

Significant oil loss without catastrophic engine damage. Could it have been a seal leak in the Arrow’s controllable pitch propeller? Loose oil lines or oil loss through a damaged oil cooler?

Could it have been something as simple as a loose oil dipstick or oil filler cap? This may have been more likely in a potentially rushed preflight on a frigid nighttime ramp? There’s nothing in the report to suggest this is what happened; it’s one of many possibilities.

Decisions, decisions! So many possibilities. It’s easy to decide what you’d do when you read an accident report because you have time to think about it, the outcome and often at least some of the cause. In the cockpit as an emergency unfolds, the pilot has incomplete and often confusing information, often few clues as to the cause, and a high workload with not enough time to figure everything out.

That’s why we depend on frequent review and practice of emergency procedures: to be able to fall back on your training when you don’t know the full picture, and if your training can’t positively resolve the problem swift, to fly with whatever capability you have remaining so you can figure it out while safely on the ground.

We teach and learn emergencies as isolated events. Detect this problem and execute that response. The reality is that any abnormal or emergency condition is merely the beginning of a series of checklist actions and decisions, not complete until you get the airplane on the ground, exit or evacuate, and survive the result.

Questions? Comments? Supportable opinions? Let us know at [email protected].

Friend and reader Brian Schiff addresses our ongoing topic (December 19 and January 2 LESSONS) of fuel planning and fuel mishaps avoidance in his January 9 webinar “The Schiff Show: Fuel Planning, Exhaustion and Starvation.” Great presentation, Brian! Readers, take a look.

Share safer skies. Forward FLYING LESSONS to a friend.

Please help cover the ongoing costs of providing FLYING LESSONS through this secure PayPal donations link. Or send a check made out to Mastery Flight Training, Inc. at 247 Tiffany Street, Rose Hill, Kansas USA 67133. Thank you, generous supporters.

Thank you to our regular monthly financial contributors:

Steven Bernstein, Montclair, NJ. Robert Carhart, Jr., Odentown, MD. Greg Cohen, Gaithersburg, MD. John Collins, Martinsburg, WV. Dan Drew. Rob Finfrock, Rio Rancho, NM. Norman Gallagher. Bill Griffith, Indianapolis, IN. Steven Hefner, Corinth, MS; Ellen Herr, Ft Myers, FL. Erik Hoel, Redlands, CA. Ron Horton. David Karalunas, Anchorage, AK. Steve Kelly, Appleton, WI. Karl Kleiderer. Greg Long, Johnston, IA. Rick Lugash, Los Angeles, CA. Richard McCraw, Hinesburg, VT. David Ovad, Resiertown, MD. Steven Oxholm, Portsmouth, NH. Brian Schiff, Keller, TX. Paul Sergeant, Allen, TX. Paul Uhlig, Wichita, KS. Richard Whitney, Warrenton, VA. Jim Preston, Alexandria, VA. Johannes Ascherl, Munich, Germany. Bruce Dickerson, Asheville, NC. Edmund Braly, Norman, OK. Steven Hefner. Lorne Sheren, New Vernon, NJ. “The Proficient Pilot,” Keller, TX. Ed Stack, Prospect Heights, IL. Kynan Sturgiss, Hereford, TX. Bluegrass Rental Properties, LLC, London, KY. John Foster.

Thanks also to these donors in 2024:

Jim Lara, Joseph Stadelmann, Dixon Smith, Barry Warner, Wayne Mudge, Joseph Vandenbosch, Ian Campbell, Jay Apt, John Kimmons, Derek Rowan, Michael Maya Charles, Ron Horton, Lauren McGavran, Gerald Magnoni, Amy Haig, Rod Partlo, Brent Chidsey, Mard Sasaki-Scanlon, SABRIS Aviation (Dave Dewhirst), Edmund Braly, Joseph Orlando, Charles Lloyd, Michael Morrow, Abigail Dang, Thomas Jaszewski Danny Kao, Gary Garavaglia, Brian Larky, Glenn Yeldezian, David Yost, Charles Waldrop, Robert Lough. Gilbert Buettner. Panatech (Henry Fiorientini). Dale Bleakney. Mark Kolesar. John Winter. Donald Bowles. David Peterson. Bill Abbatt. Bruce Jacobsen. Denny Southard, Wayne Cloburn, Ross Ditlove. “Bonanza User,” Tad Santino, Steven Scharff, Kim Caldwell, Tom Carr, Michael Smith. David Kenny. Lorne Sheren. Stu Spindel. Martin Sacks. Arthur Utay. John Whitehead. Brenda Hanson. Mark Sanz. Tim Schryer. Bill Farrell. Todd LeClair. Craig Simmons. Lawrence Peck. Howard Page. Jeffery Scherer. John Kinyon. Lawrence Copp. Joseph Stadelmann. Mark Richardson. Mark Sletten. David Hanson. Gary Palmer. Glenn Beavers. Bruce Jacobsen. Devin Sullivan. Wayne Colburn. Robert Weinstein. Robert Dunlap. Allen Leet. Peter Grass. Richard Benson.

AND THESE SUPPORTERS IN 2025: John Teipen. N. Wendell Todd. David Peterson. Jay Apt. SABRIS Aviation/Dave Dewhirst. Gilbert Buettner.

Pursue Mastery of Flight (TM)

Thomas P. Turner, M.S. Aviation Safety

Flight Instructor Hall of Fame Inductee

2021 Jack Eggspuehler Service Award winner

2010 National FAA Safety Team Representative of the Year

2008 FAA Central Region CFI of the Year

FLYING LESSONS is ©2025 Mastery Flight Training, Inc. For more information see www.thomaspturner.com. For reprint permission or other questions contact [email protected].