FLYING LESSONS uses recent mishap reports to consider what might have contributed to accidents, so you can make better decisions if you face similar circumstances. In most cases design characteristics of a specific airplane have little direct bearing on the possible causes of aircraft accidents—but knowing how your airplane’s systems respond can make the difference in your success as the scenario unfolds. So apply these FLYING LESSONS to the specific airplane you fly. Verify all technical information before applying it to your aircraft or operation, with manufacturers’ data and recommendations taking precedence. You are pilot in command and are ultimately responsible for the decisions you make.

FLYING LESSONS is an independent product of MASTERY FLIGHT TRAINING, INC.

Pursue Mastery of Flight™

This week’s LESSONS

First reports on our local news were that a woman on the ramp at the small, nontowered airfield was critically injured when struck by a spinning propeller. The airfield is home to a very active sport parachuting jump zone, across a pasture behind my back deck and about two miles from my home. We hear the jump plane almost constantly in good weather, and frequently watch the canopies open and the jumpers drift downward behind the trees.

Shortly after the first accounts follow-up reports said the woman, in her 30s, was taking photographs of jumpers loading into the jump plane when she backed into the propeller of another airplane idling on the ramp. These reports said the woman was in “extremely critical condition” when being rushed by ambulance to a Wichita-area hospital.

My first thought when hearing these early reports, trying to draw positive LESSONS from the tragedy, was about briefing people who are not familiar with lightplane operations before they enter an aircraft operating area. What would you cover in such a briefing? I considered briefing points such as these:

- Airplanes can be extremely dangerous to persons walking around airports.

- Propellers are invisible when rotating and depending on other airport activity and noise you may not even know one is spinning.

- Sometimes propellers are on the front of an airplane, sometimes they are on either wing, and sometimes they’re behind the wing or even at the end of the tail.

- When walking on a ramp, keep your head up and your eyes and ears open.

- Do not take photos or videos while walking on an airport, because you’ll be distracted by your subject and your vision narrowed by the viewfinder or camera display.

- Never walk backwards or sideways on an airport. Face the direction you’re walking.

- Still, rapidly scan left and right occasionally to see what’s around you.

- Walk in straight lines and well away from aircraft, so pilots can see you and anticipate your movement.

- Always hang on to small children at airports, and keep pets on a leash.

- If you see a sign that says “nonmovement area,” don’t be complacent. Airplanes and helicopters run and move in nonmovement areas, too.

I also thought about the horrible experience the pilot and any occupants of the airplane had after the woman backed into the Skylane’s spinning propeller. What might we pilots do to mitigate the risk on ramps and taxiways accessible to pedestrians? How about this:

- Watch pedestrians carefully to detect and predict their movement.

- Watch children and pets especially closely.

- Shut the engine(s) down before allowing passengers to exit your aircraft.

- Shut the engine(s) down before permitting passengers and others to approach your aircraft.

- Minimize the time on the ramp spent with engine(s) running. Start up, taxi away with your eyes outside, and move to an area more inaccessible to pedestrians before stopping to program your avionics, pick up your clearance or run checklists.

- During the time you are on the ramp where pedestrians may tread, keep your hand on the mixture control(s) or ignition switch(es) ready to immediately stop engines if someone gets close to the aircraft.

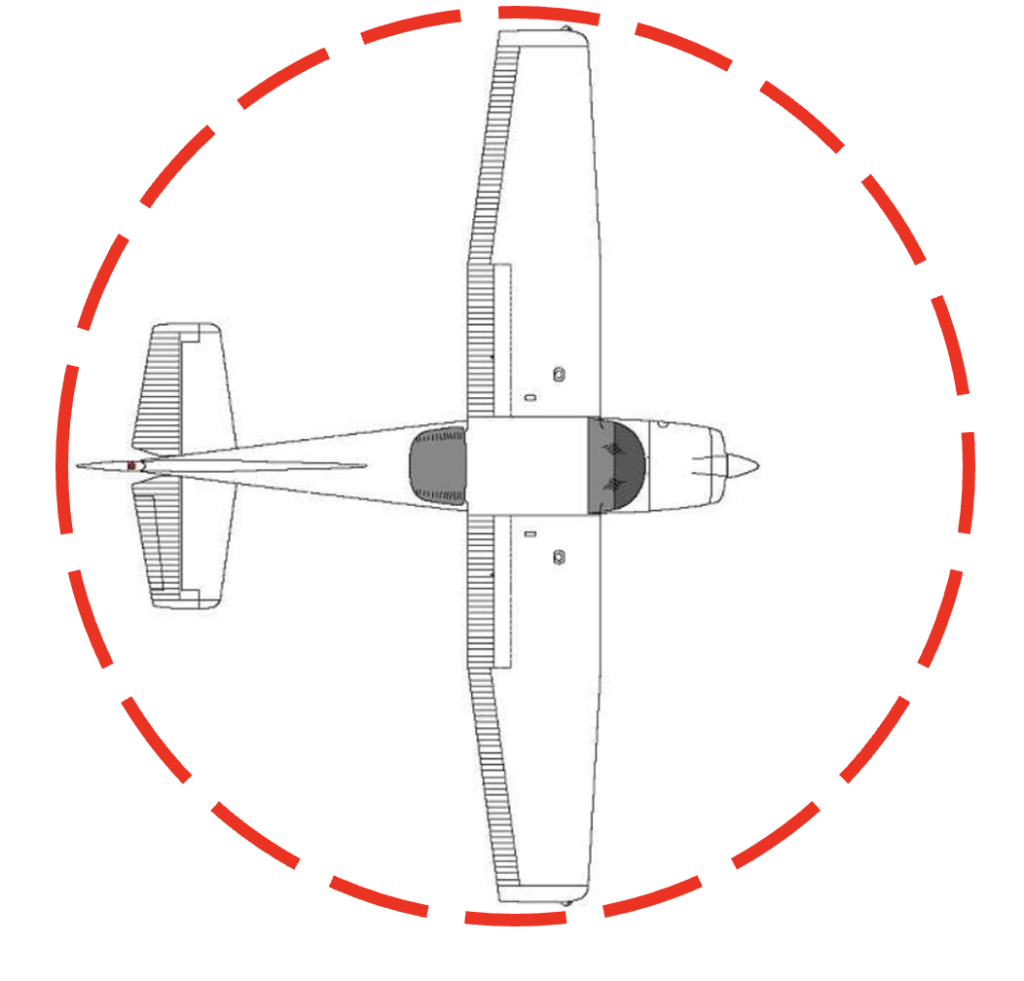

- Envision a circle the diameter of your wingspan surrounding your aircraft. In rotary wing aircraft make this twice your rotor width. If anyone comes into that area and headed toward your aircraft shut your engine(s) down immediately.

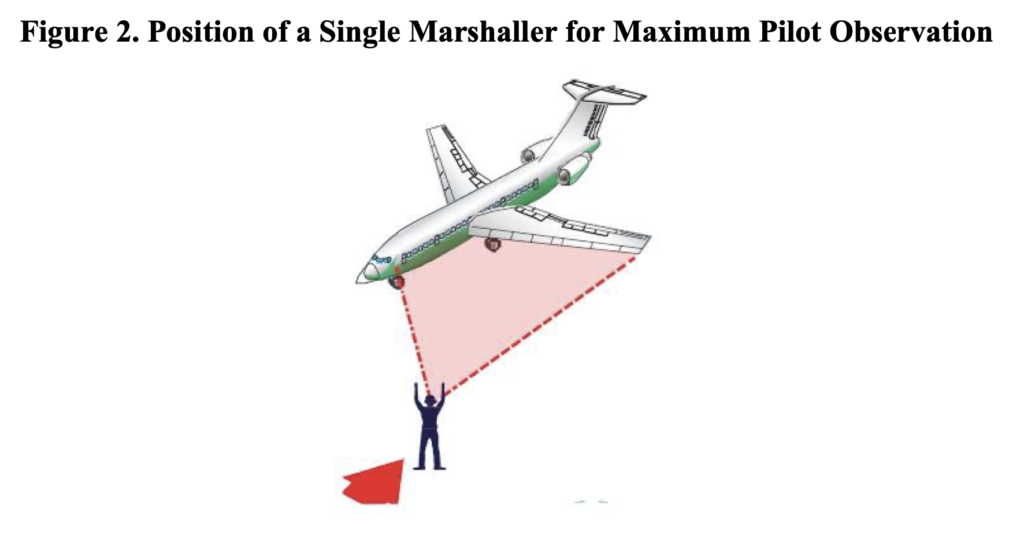

Another thought: I recall when I learned to fly that airplane marshallers would stand out in front of your wingtip, or close to wingtip distance, as they flagged pilots into parking. Nowadays (I say in my “impending curmudgeonhood” voice) spotters almost always stand directly in front of your propeller when they direct you to a stop. I think about it every time I have a marshaller—if my brakes fail now that line person is in serious danger.

Yet FAA Advisory Circular 00-34B includes an illustration of the “ideal” marshaller position for maximum visibility by the pilot…ahead of the wingtip, a far safer place for the marshaller to be as well.

Optimal marshaller position, from AC 00-34B.

Maybe we need to go back to the way I think it used to be, and train marshallers to direct pilots from in front of the wingtip, not directly in front of the aircraft—in compliance with AC 00-34B and its international equivalents.

What will likely be the definitive news report now reveals the deceased woman was a skydiver at the jump zone and professional photographer who sold photos of the jump experience to the jumpers. She was familiar with the operation and airports in general. Like so many pilots I use to derive positive LESSONS, this was likely a simple case of distraction, chance, bad luck, and being literally in the wrong place at the wrong time.

The FAA preliminary report, though objectively reporting the facts of this horribly subjective accident, tells us:

[The Cessna 182Q] was idling on [the] runway awaiting skydivers and a photographer exited [the] aircraft and backed up into the propeller while taking pictures.

As safety conscious people who control access to airplane movement and nonmovement areas, we all have a responsibility to:

- Educate, brief and escort passengers and persons who will be on the ground near aircraft;

- Follow the best practice of shutting down before loading or unloading passengers;

- Minimize our time spent with the engine(s) running on the ground in places where pedestrians may appear;

- Properly educate line service personnel for their own protection as well as ours; and

- Be vigilant and to shut down immediately if someone on the ground enters the space within the wingspan or twice the rotor span of your aircraft.

Can you think of more LESSONS inspired by this awful event?

Questions? Comments? Supportable opinions? Let us know at [email protected].

Debrief

Readers write about past FLYING LESSONS

Frequent Debriefer John Scherer writes about the October 17 LESSONS:

Hi Tom, I have three bird strikes that I remember well. The first was in a T-38 departing Colorado Springs [Colorado]. I was climbing at 300 KIAS. I saw a flash on the right side of the airplane. A small bird dented the right wing honeycomb section outside the engine intake. No effect on controllability. I continued back to my home base of Minot AFB [Air Force Base], North Dakota.

The second was at Minot. On takeoff at about 10 feet, I took a bird in the left engine. I kept the throttles at full afterburner. Once at a safe altitude, I retarded the left engine to idle and did a visual “heavyweight “single engine return to the runway I had just taken off from. Final approach speed was about 180 KIAS as I recall. Landing was routine and the engine had to be replaced.

The third one was on a touch and go at Quantico Marine Corp Base [Virginia]. I taught at the aero club. I was in a Cessna 152 with a student and a seagull hit the windshield just as we were about 10 feet in the air. I sensed no damage and we did a closed pattern and landed. No damage.

I can’t remember if I filled out a bird strike form on any of these flight, but I probably did. Keep up your great emails!

And keep sending relevant stories from your flying career, John. Thank you.

More to say? Let us learn from you, at [email protected]

Share safer skies. Forward FLYING LESSONS to a friend.

Please help cover the ongoing costs of providing FLYING LESSONS through this secure PayPal donations link. Or send a check made out to Mastery Flight Training, Inc. at 247 Tiffany Street, Rose Hill, Kansas USA 67133. Thank you, generous supporters.

Thank you to our regular monthly financial contributors:

Steven Bernstein, Montclair, NJ. Robert Carhart, Jr., Odentown, MD. Randy Carmichael, Kissimmee, FL. Greg Cohen, Gaithersburg, MD. John Collins, Martinsburg, WV. Dan Drew. Rob Finfrock, Rio Rancho, NM. Norman Gallagher. Bill Griffith, Indianapolis, IN. Steven Hefner, Corinth, MS; Ellen Herr, Ft Myers, FL. Erik Hoel, Redlands, CA. Ron Horton. David Karalunas, Anchorage, AK. Steve Kelly, Appleton, WI. Karl Kleiderer. Greg Long, Johnston, IA. Rick Lugash, Los Angeles, CA. Richard McCraw, Hinesburg, VT. David Ovad, Resiertown, MD. Steven Oxholm, Portsmouth, NH. Brian Schiff, Keller, TX. Paul Sergeant, Allen, TX. Paul Uhlig, Wichita, KS. Richard Whitney, Warrenton, VA. Jim Preston, Alexandria, VA. Johannes Ascherl, Munich, Germany. Bruce Dickerson, Asheville, NC. Edmund Braly, Norman, OK. Steven Hefner. Lorne Sheren, New Vernon, NJ. “The Proficient Pilot,” Keller, TX. Ed Stack, Prospect Heights, IL

And thanks to these donors in 2024:

Jim Lara, Joseph Stadelmann, Dixon Smith, Barry Warner, Wayne Mudge, Joseph Vandenbosch, Ian Campbell, Jay Apt, John Kimmons, Derek Rowan, Michael Maya Charles, Ron Horton, Lauren McGavran, Gerald Magnoni, Amy Haig, Rod Partlo, Brent Chidsey, Mard Sasaki-Scanlon, SABRIS Aviation (Dave Dewhirst), Edmund Braly, Joseph Orlando, Charles Lloyd, Michael Morrow, Abigail Dang, Thomas Jaszewski Danny Kao, Gary Garavaglia, Brian Larky, Glenn Yeldezian, David Yost, Charles Waldrop, Robert Lough. Gilbert Buettner. Panatech (Henry Fiorientini). Dale Bleakney. Mark Kolesar. John Winter. Donald Bowles. David Peterson. Bill Abbatt. Bruce Jacobsen. Denny Southard. Wayne Cloburn. Ross Ditlove. “Bonanza User,” Tad Santino, Steven Scharff

Pursue Mastery of Flight (TM)

Thomas P. Turner, M.S. Aviation Safety

Flight Instructor Hall of Fame Inductee

2021 Jack Eggspuehler Service Award winner

2010 National FAA Safety Team Representative of the Year

2008 FAA Central Region CFI of the Year

FLYING LESSONS is ©2024 Mastery Flight Training, Inc. For more information see www.thomaspturner.com. For reprint permission or other questions contact [email protected].