FLYING LESSONS uses recent mishap reports to consider what might have contributed to accidents, so you can make better decisions if you face similar circumstances. In most cases design characteristics of a specific airplane have little direct bearing on the possible causes of aircraft accidents—but knowing how your airplane’s systems respond can make the difference in your success as the scenario unfolds. So apply these FLYING LESSONS to the specific airplane you fly. Verify all technical information before applying it to your aircraft or operation, with manufacturers’ data and recommendations taking precedence. You are pilot in command and are ultimately responsible for the decisions you make.

FLYING LESSONS is an independent product of MASTERY FLIGHT TRAINING, INC.

Pursue Mastery of Flight™

This week’s LESSONS

Reader, instructor and accident investigator Jeff Edwards writes about the August 1 LESSONS:

Re[garding] comments on problems away from home. Don’t forget to review 91.213 (d) and its related AC 91-67 as well as the POH and AFM when it comes to flying with inoperative equipment.

The same could be said for similar regulations for pilots operating under non-U.S. regulatory structures.

One of the many reasons commercial airline and professionally flown corporate aviation have far, far better accident and especially fatal accident rates than owner-flown personal and business aviation is that most commercial and all airline operations have published Operations Specifications (“OpSpecs”). An OpSpec is essentially a negotiated contract between the aircraft operator and regulators as to how the airplane will be flown when, among other things, dealing with inoperative equipment, including regulator-approved Minimum Equipment Lists (MELs).

A big part of the safety benefit of an OpSpec is that many decisions are made beforehand, hazards contemplated and risks managed. When an issue arises in operation there’s less chance of making a bad decision under the pressure to “go” at the moment, because the flight department and its pilots have agreed beforehand how to handle these types of situations. It’s harder to violate a rule to which you have voluntarily, mutually and publicly committed in writing.

Pilots of personal and business use aircraft don’t have these individualized binding contracts with the regulatory authority or prior commitment with the peer review of a flight department. But we still have a mandatory Operations Specification we can use the same way, with which we can realize much of the same safety benefit enjoyed by our career-pilot friends in their flying jobs. That OpSpec is Federal regulation or it’s international equivalent.

14 CFR 91.213 (and the corresponding rules of most international regulation bodies) addresses Inoperative Instruments and Equipment. It lays out the hierarchy of requirements when equipment is inoperative:

- If the operator has an MEL then the aircraft must be operated within the provisions of that agreement. If the operator does not have an approved MEL, then any inoperative equipment must:

- Not be an item required by regulation for the type of operation to be flown, for example, day VFR, night, or IFR and

- Not be an item that is listed in the Kinds of Operation and Equipment List (KOEL) in the Pilot’s Operating Handbook orAirplane Flight Manual for that make and model of aircraft.

For example, you fly a Beech F33A Bonanza (why is it always a Bonanza with me? Because I have access to all the POHs). One of the fuel quantity indicators isn’t working correctly. You just filled the fuel tanks to the top, so you know how much fuel is on board. Can you fly with an inoperative fuel gauge?

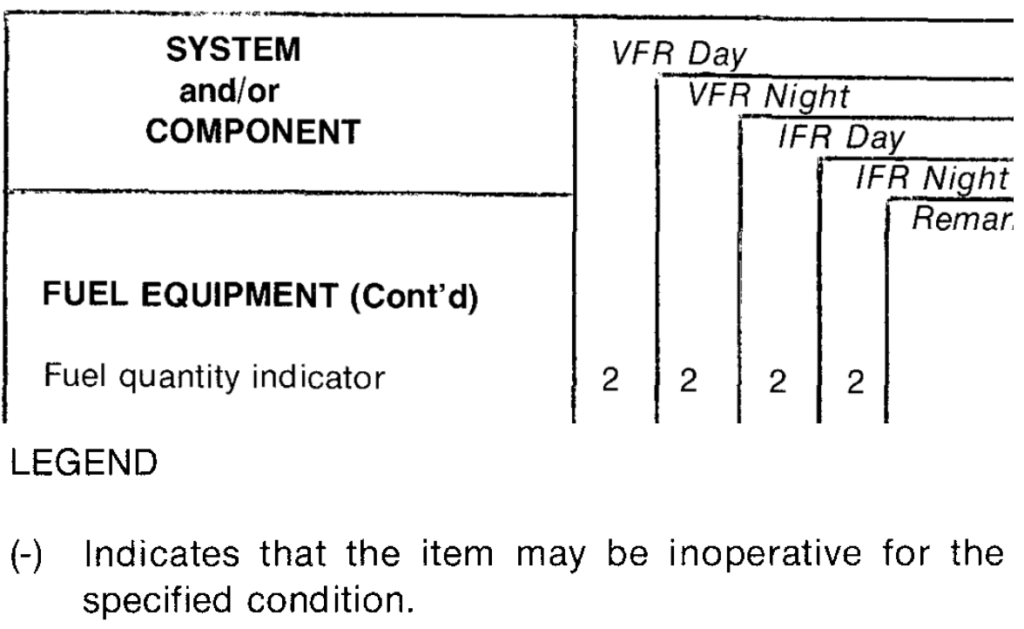

You don’t have an FAA-approved MEL. 14 CFR 91.205 requires a “Fuel gauge indicating the quantity of fuel in each tank.” Presumably that means the gauges must be working, too. Driving the point home, the F33A POH KOEL, part of Section II, Limitations, of the handbook, indicates two operable fuel gauges must be installed for any type of flight. Even after confirming visually that the fuel tanks are full, you cannot legally operate without both (2) fuel gauges functioning properly.

F33A POH KOEL excerpt for fuel gauges

Our noncommerical OpSpec, the regulations, gives us the same benefit enjoyed by the airline and the corporate flight department—if you commit to following the rules. Make this commitment at zero altitude, zero airspeed and one G and you’ll be less likely to yield to temptation when a situation arises. In this particular case this means delaying the flight until the fuel gauge is fixed, or if you need to take the airplane somewhere to make this happen, to obtain a Special Flight Permit (“ferry permit”) from the regulating authorities.

Why is that safer than just flying without the permit? To operate on a special authorization you must have a mechanic look at the aircraft and confirm, with his/her signature, that the flight can be conducted safely. The permit will also likely require the flight be conducted in day, visual conditions and only with required flight crew aboard—no passengers. For aircraft insurance to be valid you’ll need to have your underwriters approve the ferry flight in advance; by definition an aircraft operating on a ferry permit is not airworthy, and insurance policies exclude coverage if the pilot flies the aircraft in a known unairworthy condition.

In other words, to get a ferry permit you have mechanics, regulators, underwriters and likely other pilots review the condition and your plans for dealing with it. This group becomes your personal “flight department” that evaluates the airplane, double-checks your decision-making, and helps you manage the risk of flying the aircraft in its current condition.

The regulations-as-OpSpecs approach serves you well in cases where specific aircraft components fail. But what about when conditions arise that are not directly addressed by the POH/AFM, the KOEL and the regulations? For example, what about the case that started this discussion in the August 1st LESSONS, a fuel leak found away from home?

Some things just aren’t listed in 91.205 or a KOEL. Find a missing wing bolt? See corrosion on a primary flight control? Notice chord showing through one of the main landing gear tires? Locate a crack in a cylinder? None of these types of things are directly addressed in the regulations or listed on a Kinds of Operations and Equipment List.

What if what you find is less obvious, such as a cracked windscreen, a weak battery…or a suspected fuel leak like the one that prompted our August 1st LESSONS?

This is where you must use informed judgment. It’s also when you must maintain discipline in your decision-making. Perhaps more practice with your personal OpSpecs will give you a keener eye for other discrepancies, and the mindset to avoid rationalizing conditions using more judgment…even consulting your “personal flight department”—trusted mechanics, flight instructors and others—to help you review the condition, positively confirm its cause and operational impact, and make an informed, dispassionate decision about whether and how to address it before flight.

Questions? Comments? Supportable opinions? Let us know at [email protected].

Share safer skies. Forward FLYING LESSONS to a friend.

Please help cover the ongoing costs of providing FLYING LESSONS through this secure PayPal donations link. Or send a check made out to Mastery Flight Training, Inc. at 247 Tiffany Street, Rose Hill, Kansas USA 67133. Thank you, generous supporters.

Thank you to our regular monthly financial contributors:

Steven Bernstein, Montclair, NJ. Robert Carhart, Jr., Odentown, MD. Randy Carmichael, Kissimmee, FL. Greg Cohen, Gaithersburg, MD. John Collins, Martinsburg, WV. Paul Damiano, Port Orange, FL. Dan Drew. Rob Finfrock, Rio Rancho, NM. Norman Gallagher. Bill Griffith, Indianapolis, IN. Steven Hefner, Corinth, MS; Ellen Herr, Ft Myers, FL. Erik Hoel, Redlands, CA. Ron Horton. Robert Hoffman, Sanders, KY. David Karalunas, Anchorage, AK. Steve Kelly, Appleton, WI. Karl Kleiderer. Greg Long, Johnston, IA. Rick Lugash, Los Angeles, CA. Richard McCraw, Hinesburg, VT. David Ovad, Resiertown, MD. Steven Oxholm, Portsmouth, NH. Brian Schiff, Keller, TX. Paul Sergeant, Allen, TX. Ed Stack, Prospect Heights, IL; Paul Uhlig, Wichita, KS. Richard Whitney, Warrenton, VA. Jim Preston, Alexandria, VA. Johannes Ascherl, Munich, Germany. Bruce Dickerson, Asheville, NC. Edmund Braly, Norman, OK. Steven Hefner. Lorne Sheren, New Vernon, NJ

And thanks to these donors in 2024:

Jim Lara, Joseph Stadelmann, Dixon Smith, Barry Warner, Wayne Mudge, Joseph Vandenbosch, Ian Campbell, Jay Apt, John Kimmons, Derek Rowan, Michael Maya Charles, Ron Horton, Lauren McGavran, Gerald Magnoni, Amy Haig, Rod Partlo, Brent Chidsey, Mard Sasaki-Scanlon, SABRIS Aviation (Dave Dewhirst), Edmund Braly, Joseph Orlando, Charles Lloyd, Michael Morrow, Abigail Dang, Thomas Jaszewski Danny Kao, Gary Garavaglia, Brian Larky, Glenn Yeldezian, David Yost, Charles Waldrop, Robert Lough. Gilbert Buettner. Panatech (Henry Fiorientini). Dale Bleakney. Mark Kolesar. John Winter. Donald Bowles. David Peterson

NEW THIS WEEK: Bill Abbatt

Pursue Mastery of Flight

Thomas P. Turner, M.S. Aviation Safety

Flight Instructor Hall of Fame Inductee

2021 Jack Eggspuehler Service Award winner

2010 National FAA Safety Team Representative of the Year

2008 FAA Central Region CFI of the Year

FLYING LESSONS is ©2024 Mastery Flight Training, Inc. For more information see www.thomaspturner.com. For reprint permission or other questions contact [email protected].