FLYING LESSONS uses recent mishap reports to consider what might have contributed to accidents, so you can make better decisions if you face similar circumstances. In most cases design characteristics of a specific airplane have little direct bearing on the possible causes of aircraft accidents—but knowing how your airplane’s systems respond can make the difference in your success as the scenario unfolds. So apply these FLYING LESSONS to the specific airplane you fly. Verify all technical information before applying it to your aircraft or operation, with manufacturers’ data and recommendations taking precedence. You are pilot in command and are ultimately responsible for the decisions you make.

FLYING LESSONS is an independent product of MASTERY FLIGHT TRAINING, INC.

Pursue Mastery of Flight™

This week’s LESSONS:

Some time back, prompted by a FLYING LESSONS reader, I asked for stories of inflight decision-making done right. Most of what we learn about ADM—aeronautical decision making—comes from bad examples: aircraft accident reports, because accidents are what get documented and reported. Several of you responded; I’ve used some of your stories, and I have a few more on deck. Another reader suggested I might have some stories myself, and I promised to get to one or two when the time was right.

It’s Thanksgiving here in the U.S., so this week I’ll relate an ADM example from a Thanksgiving trip I took five years ago. Long-time readers have seen this before, and I hope you’ll enjoy the refresher. All readers, it’s up to you: what might you have done differently, and why?

“Aim for the Blue!”

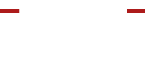

I stared into my cell phone, sitting on a narrow couch in the FBO at Cape Girardeau, Missouri (KCGI). Returning to Wichita after a family Thanksgiving celebration in Ohio we’d left a day earlier than planned, on Sunday. A major winter storm was scheduled to hit Kansas Sunday and impact Ohio Monday morning. It was warm ahead of the front; my plan was to fly southwest as far as we could on Sunday, around the freezing and blizzard conditions that were also dropping tornadoes around St. Louis, and then scoot home in clear skies behind the storm Monday morning.

After a two-hour fog delay, we launched toward our overnight at KCGI along the Mississippi River in the “bootheel” of Missouri. I stayed low in mostly clear skies, flying at 4000 feet into a headwind that hit as high as 52 knots. Good thing the Bonanza I was flying trues out at 168 knots.

For the last 40 minutes I deviated around a few shafts of rain, then plunged into thick stratus clouds. The temperature was still +10°C at 4000 feet so I wasn’t worried about ice—although this time of year I’m always thinking about it. A check of weather at the tower-controlled airport revealed a roughly 1000-foot ceiling with great visibility beneath and a surface wind from 140° at 17 knots—sounding a lot better than the 180° at 19 gusting to 29 knots that I’d seen at times on XM weather on the way down. Given the newest weather update, when asked by Center I requested the RNAV (GPS) 10 approach, to the longer and wider runway more aligned with the reported wind.

After flying the holding pattern-style course reversal (below minimum vectoring altitude; no vectors), I found I needed an almost 40° crab angle to remain aligned with the final approach course. Handed off to the tower, the controller gave me a wind check—180° at 25 knots. Even before he asked, I decided I wanted to circle-to-land on Runway 20. Tower cleared me to land and I touched down smoothly, not requiring much ground roll into the stiff wind. It rained hard that night, and afterward temperatures plunged well below freezing. My wife and I enjoyed a quiet post-holiday decompression at the local Drury Inn, and the Bonanza spent the night in a heated hangar at Cape Aviation.

The forecast called for stiff winds to drive the clouds away, with overcast skies improving to scattered around 10 am. I filed for an 11 am departure the next day for the roughly three-hour flight to Wichita, still bucking a strong forecast wind at 6000 feet. When we awoke at 7 am and I checked the weather again, however, it was still 2800 overcast and below freezing at Cape Girardeau. The clouds extended halfway across Missouri, and conditions clearly called for ice in the clouds. I told my wife we could take our time and have a leisurely brunch before going to the airport. Then I amended my departure time until 12 pm: the new, forecast clearing time.

First Temptation

So at noon I was still sitting on the couch in the FBO staring into my phone, checking and re-checking the satellite images, ceilings, visibilities, cloud tops and (the lack of) Pilot Reports…and things were not improving. As much as I study accident scenarios, as much as I’m a stickler for limitations and the rules, the longer I waited the more I consciously felt myself being tempted to go ahead and “give it a try.” I rationalized that I could launch into the clouds and climb through the icy layer. I mulled over the relative merits of climbing rapidly through the clouds at VY speed versus a shallower climb at the similar-winged Beech Baron’s ice-certified 130-knot minimum ice penetration speed. I even mentioned to my wife that, if we launched and I started to pick up ice, I could “just” turn around and land back at Cape G.

When I heard myself actually say that, out loud, I stopped then and there. I learned I am just as susceptible to temptation and “get home-it is” as a newly minted Private Pilot. We all are. I told my wife we’d just have to wait it out.

The NTSB record is full of pilots who thought they’d “give it a try,” or who convinced themselves they had an “out” they could exercise before things got out of hand. Being away from home for five days at that point, with my wife—who is great about weather delays—wanting to get home (I felt more pressure to get her there than she was actually exerting on me), and with hotel, restaurant, rental car and hangar fees slowly but continually adding up, I can see how even someone who is usually as disciplined or attuned to the mishap record as I try to be, may still be tempted to launch into unacceptable conditions…or continue into them, until it is too late.

Confirmation, and Inspiration

Another pilot entered the FBO lounge, a young man who had flown a Piper M600 turboprop in earlier that morning and was waiting for a passenger. I asked, and he told me he had encountered “a lot” of clear ice on the way in, and that was while “at 280 knots descending at 2500 feet per minute” through the clouds to minimize his exposure.

I called up the latest weather on my phone, again. The satellite showed clouds continuing to break up, very slowly, along my route of flight about 70 miles west of where I sat. Fifty-two miles to the southwest, however, the cloud shelf ended at a huge gap near Poplar Bluff, Missouri that extended another 100 miles or more west. It was reportedly clear at Wichita; my wife was online looking at “highway cams” around town and the sky was completely clear there. A new Plan B began to form in my mind.

I file IFR for virtually all trips away from my home base local area. I like working “in the system”; I enjoy the added safety of someone watching over me, and the reduced workload when flying through Class B, C and D airspace. I am so spring-loaded to filing and flying IFR I was in an IFR mindset, knowing that I could not go because to depart en route would require me to climb into ice-laden clouds. The M600 pilot confirmed this.

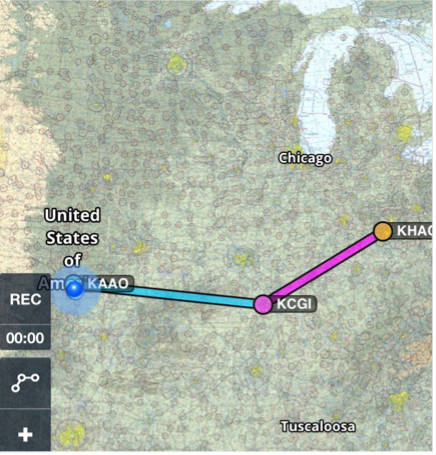

“Plan B”: VFR under the clouds to Poplar Bluff, then climb in clear skies to pick up my clearance to Wichita

A more creative plan, however, was to fly VFR in great visibility, under the cloud deck, to Poplar Bluff (KPOF). From there, the satellite image told me, I could climb VFR to be over the thinning clouds further west, then contact Air Traffic Control to obtain an IFR clearance for the remainder of the flight. I’d avoid all chances of ice because the skies were entirely clear near my destination, and the clouds out west were so thin there was no mention of ice there in the updated Current Icing Potential and Forecast Icing Potential reports.

I’m very familiar with the low, flat terrain in the Missouri Bootheel. I’ve flown across it many times. With the reported forecasts I could easily fly at 1500 feet above ground level…1800 feet, most likely, and still be at least 500 feet below the clouds. I was confident that the VFR hop to Poplar Bluff was entirely safe.

Upon reaching Poplar Bluff (KPOF) I would turn toward home. The terrain rises farther west, so I would fly no more than 20 miles that way before deciding (1) I could make my unrestricted visual climb, or (2) I would immediately turn back and land at KPOF.

Second Temptation

I preflighted the airplane; we loaded up, I fired up XM Weather on my Garmin 796 portable GPS and called up the satellite image, and I called Ground for a VFR departure to Poplar Bluff, requesting 1800 feet. With departure instructions I taxied to the runup area.

As I completed my Before Takeoff checklist and flipped to Tower frequency, I heard the pilot of another Bonanza (yeah, with me it’s always a Bonanza!) check in on the instrument approach. Temptation reared again. Someone else was up there in it; only a handful of Bonanzas are certificated or equipped for flight in icing, so if he could do it I could do it too. The sky was getting lighter in my direction of flight, meaning the skies were clearing there. Looking up, I thought I might be able to see wisps of blue sky among the gray.

I found myself wanting to rationalize picking up my clearance and departing IFR after all.

I called tower with a request: Could he ask the Bonanza pilot whether he was picking up any ice on the approach, and if he could report the cloud tops. Tower asked him; the answer to both was “yes”: mixed ice during the descent, and cloud tops at 5000 feet. That meant about 2000 feet of ice-laden clouds for climb. “Stupid,” I told myself, “no amount of ice is acceptable.” I called the tower again and said, “I think I’ll continue with my plan. Ready for departure Runway 28, VFR southwestbound.” “Cleared for takeoff,” the controller replied. “Have a good flight to Poplar Bluff.”

“Aim for the Blue”

Airborne, the Bonanza quickly climbed to 1800 feet MSL, about 1500 feet above the flat terrain and 600 feet above the highest obstacle in the quadrant ahead—a transmission tower nicely painted in “safe” white on the airplane’s synthetic vision display, well to one side of our course. Above was grey stratus, but the horizon was that bright mid-yellow that hints of clearing skies ahead. About 15 miles out the clouds above began to part, quickly becoming a broken layer ahead and to my right, the direction we ultimately wanted to go. I could see that the clouds here were very thin, only a couple of hundred feet thick. Time for the second half of Plan B.

Since I was low I knew it was a long-shot to contact Memphis Center for my clearance. But it was worth a shot. I upped the odds by disabling the squelch on my comm radio, which very effectively increases reception range. It was scratchy, but Center answered my call from 20 southwest of KCGI immediately, saying: “Are you off Cape Girardeau?”

I expected to have to negotiate my clearance or even re-file the entire flight plan in the air. When ATC asked if I was off KCGI, however, that told me two things: (1) he knew who I was and was expecting me, and (2) I was close enough to my filed IFR route of flight that he was ready to give me my clearance. Sure enough, when I answered I was immediately cleared direct from my current position to destination, climb and maintain 6000 feet. A couple of screen touches and I had a magenta line direct to home, turned the airplane westward and began to climb into a gap.

My wife put on the headset I’d plugged in for her before we boarded and called from the back seat, “Aim for the blue.” As I made the turn a big swatch of blue sky opened; she knew that’s where we needed to go to make it home without any chance of ice. Although she is not a pilot (I introduce her as a Rated Command Passenger), “aim for the blue” was the best decision all day.

We climbed easily through that hole without having to make any turns. The clouds quickly evaporated beneath us, although behind us thick grey skies still covered Cape Girardeau. Bucking a strong wind it took three hours to fly the 367 miles from KCGI to Wichita. But after climbing out there was not a cloud in the sky the rest of the way.

This Week’s LESSONS:

- No matter what your experience, we are all susceptible to “get home-itis” that tempts us to think up all sorts of rationalizations to support a “go” decision.

- Often pilots feel more pressure to meet a passenger or family member’s schedule than even that person exerts on us him/herself. An educated non-pilot can probably tell when they don’t want you to fly and, presented the facts, will support your delay/divert/cancel decision. I thought my wife was pressuring me to go, but she wasn’t.

- I’m convinced that most pilots who are involved in weather-related crashes probably know even before they take off that they shouldn’t be flying in those conditions. The problem is that they overestimate their abilities or the capability of the airplane; contrive an unusual escape plan in case things go wrong that may or may not solve the problem; and/or succumb to peer pressure because other pilots are out flying in it. They allow these rationalizations to overrule their better judgment.

- The only defense against rationalization is to take a firm stand on the rules of certification, regulation and currency: no compromises.

- When ice exists or is forecast, or in an airplane certified for flight in icing conditions a reputable PIREP reports “a lot” of ice on an airplane much more powerful and better-equipped then yours, remaining visual and to “aim for the blue” is the only way to fly.

Happy Thanksgiving, everyone, in and outside the United States. May all your preflight and inflight decisions be good ones.

Questions? Comments? Supportable opinions? Let us know at [email protected].

Debrief:

Readers write about recent FLYING LESSONS:

Reader, avionics expert and flight instructor John Collins continues last week’s Debrief discussion about the 50/70 Rule:

I agree with commenter Damon Overboe regarding the 50/70 rule. The 50/70 rule comes from the following equations of motionand assumes the initial velocity is zero and the acceleration is constant “A” up to reaching lift off speed.

Assume V1 is lift off speed and S1 is the distance for the takeoff roll. S2 is half the distance for the ground roll and V2 is the speed expected at half of the takeoff roll distance. The distance from the start of the takeoff roll to lift off and the lift off speed are both found in the POH performance tables.

In general, when the starting speed is zero and there is a constant acceleration, the equations of motion to calculate the distance as a function of the acceleration “A” and Velocity “V” is:

S = (V**2)/2A.

This may be rearranged and expressed in terms of the V speed as:

V = square root (S * 2A).

So,

V1 = square root (S1*2*A),

V2 = square root (S2*2*A).

But since S2 is half of S1, you can substitute S1/2 for S2

V2 = square root (S1*A).

If you Express V2/V1 so that V2 is a fraction of V1, you get:

V2/V1 = Square root ((S1*A )/S1*2*A))

This simplifies to:

V2/V1 = Square root (1/2).

= .707 or expressed as a percent, is 70.7%, hence the 70% part of the rule.

The 50/70 rule is not based on the runway length, it is based on starting from a full stop and lined up on the runway. Then power is applied (usually full power) and the brakes are released to provide a constant acceleration. Physics 1 and algebra 1 are all that is involved if you know what V1 is in order to calculate what V2 should be. S2 is half of S1 from the POH.

I’ve never seen a mathematical proof of the 50/70 rule. Thank you, John, that’s fascinating. As I told Damon last week, the 50/70 Rule is not my rule. But he and you, John, are helping me correct those who think it is based on runway length when in fact it describes the expected takeoff ground roll distance. Thanks, John!

More to say? Let us learn from you, at [email protected].

Share safer skies. Forward FLYING LESSONS to a friend

Please help cover the ongoing costs of providing FLYING LESSONS through this

secure PayPal donations link. Or send a check made out to Mastery Flight Training, Inc. at 247 Tiffany Street, Rose Hill, Kansas USA 67133.

Thank you, generous supporters.

Special thanks to these donors for helping with the Mastery Flight Training website rebuild and beyond:

Karl Kleiderer, Jeffery Scherer, Ken Newbury, William Eilberg, Wallace Moran, Lawrence Peck, Lauren McGavran, Stanley Stewart, Stu and Barbara Spindel, Danny Kao, Mark Sanz, Wayne Mudge, David Peterson, Craig Simmons, John and Betty Foose, Kendell Kelly, Sidney Smith, Ben Sclair, Timothy Schryer, Bruce Dickerson, Lew Gage, Martin Pauly, Theodore Bastian, Howard Greenberg, William Webber, Marc Dullude, Ian O’Connell, Michael Morrow, David Meece, Mike Gonce, Gianmarco Armellin, Mark Davis, Jason Ennis, William Moore, Gilbert Buettner, Don Denny, John Kolmos, LeRoy Cook, Mark Finklestein, Rick Lugash, Tom Carr, John Zimmerman, Lee Perrin, Bill Farrell, Kenneth Hoeg, William Jordan Jr., Mark Rudo, Boyd Spitler, Michael Brown, Gary Biba, Meaghan Cohen, Robert Chatterton, Lee Gerstein, Peter Tracy, Dan Drew, David Larson, Joseph McLaughlin, Nick Camacho, Paul Uhlig, Paul Schafer, Gary Mondry, Bruce Douglass, Joseph Orlando, Ron Horton, George Stromeyer, Sidney Smith, William Roper, Louis Olberding, George Mulligan, David Laste, Ron Horton, John Kinyon, Doug Olson, Bill Compton, Ray Chatelain, Rick McCraw, David Yost , Johannes Ascherl, Rod Partio, Bluegrass Rental Properties, David Clark, Glenn Yeldezian, Paul Sherrerd, Richard Benson, Douglass Lefeve, Joseph Montineri, Robert Holtaway, John Whitehead; Martin Sacks, Kevin O’Halloran, Judith Young

Thanks to our regular monthly financial contributors:

Steven Bernstein, Montclair, NJ. Robert Carhart, Jr., Odentown, MD. Randy Carmichael, Kissimmee, FL. James Cear, South Jamesport, NY. Greg Cohen, Gaithersburg, MD. John Collins, Martinsburg, WV. Paul Damiano, Port Orange, FL. Dan Drew. Rob Finfrock, Rio Rancho, NM. Norman Gallagher. Bill Griffith, Indianapolis, IN. Steven Hefner, Corinth, MS; Ellen Herr, Ft Myers, FL. Erik Hoel, Redlands, CA. Ron Horton. Robert Hoffman, Sanders, KY. David Karalunas, Anchorage, AK. Steve Kelly, Appleton, WI. Karl Kleiderer. Greg Long, Johnston, IA. Rick Lugash, Los Angeles, CA. Richard McCraw, Hinesburg, VT. David Ovad, Resiertown, MD. Steven Oxholm, Portsmouth, NH. Brian Schiff, Keller, TX. Paul Sergeant, Allen, TX. Ed Stack, Prospect Heights, IL; Robert Thorson, Reeders, PA. Paul Uhlig, Wichita, KS. Richard Whitney, Warrenton, VA. James Preston, Alexandria, VA.

Pursue Mastery of Flight

Thomas P. Turner, M.S. Aviation Safety

Flight Instructor Hall of Fame Inductee

2021 Jack Eggspuehler Service Award winner

2010 National FAA Safety Team Representative of the Year

2008 FAA Central Region CFI of the Year

FLYING LESSONS is ©2023 Mastery Flight Training, Inc. For more information see www.thomaspturner.com. For reprint permission or other questions contact [email protected]